HS2 has become a symbol of national incompetence. Spend its billions elsewhere

Britain gave the world railways, yet this week we are told the government can’t even estimate how much HS2 will cost, let alone when it will be built. As Chris Blackhurst argues, it should never have happened in the first place

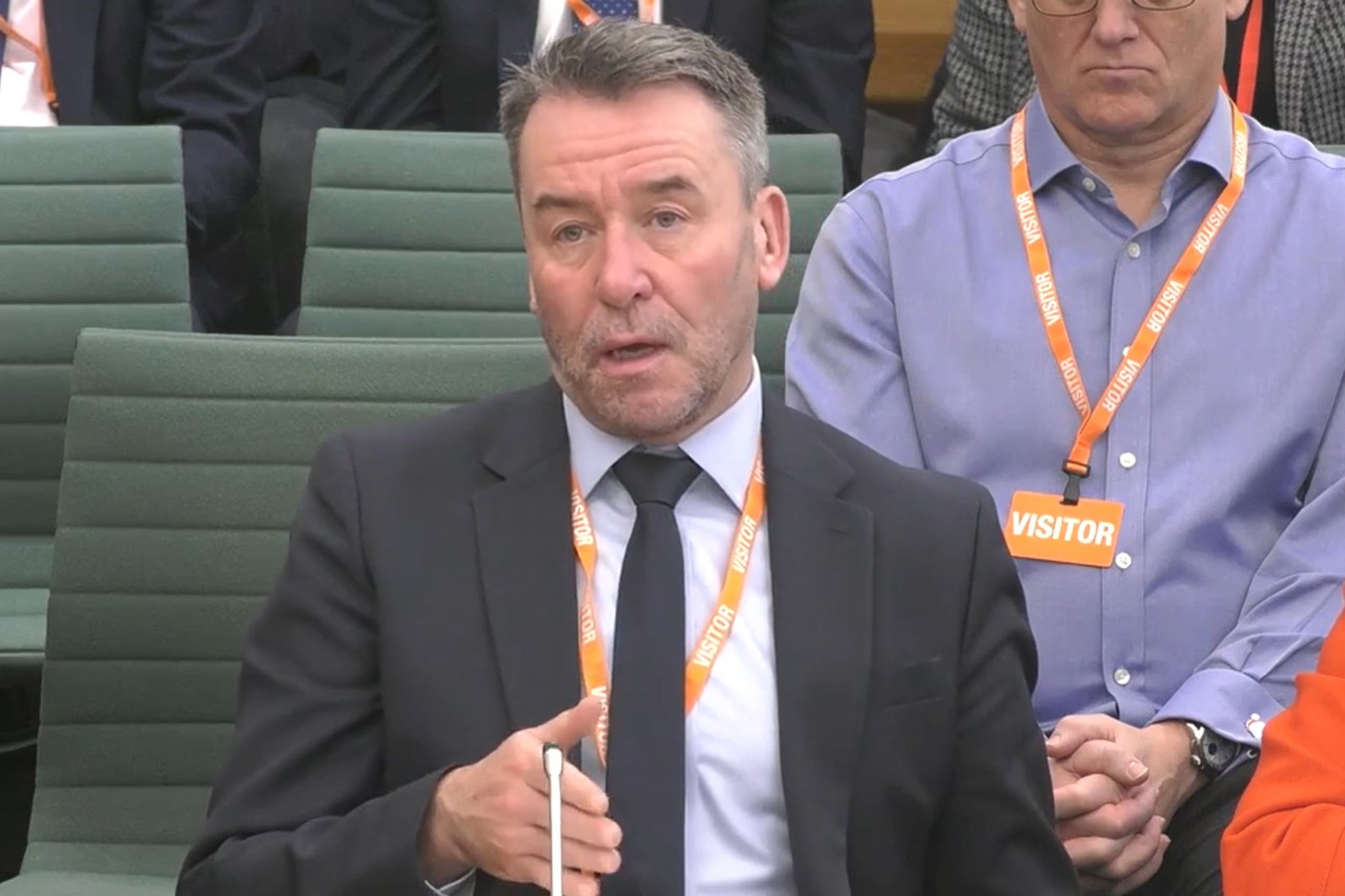

The new year has not begun but already a strong candidate has emerged for word of 2025: it’s “reset”. We’ve just seen one in Keir Starmer’s overhaul of government priorities. Now again, with Mark Wild, chief executive of HS2, telling MPs the high-speed railway requires a rethink.

For emphasis, Wild prefixed it with “fundamental”, so a “fundamental reset” is a must. What’s the betting we will see more of the same in 2025, in the economy, NHS, foreign relations, defence, climate change. The scope for tearing everything up and starting again, as if the previous mess never happened, is endless.

Not that there is any rush. Don’t imagine for a second that the HS2 “reset” will see a round-the-clock, all-out effort. HS2 may be designed to hasten travel time from A to B but Wild says the new plan will not be ready until mid-2026 at the earliest. “We have to acknowledge that HS2 in its core mission to control costs has failed,” he said. “We must break the cycle.”

Acknowledging the problem takes a nano-second, but breaking and starting over, we’re apparently looking at 18 months – and bearing in mind this is HS2, that’s a schedule that is likely to lengthen.

Wild also said: “Construction started way too early, The rush to start before mature design consents was really, in retrospect, a mistake.” He added that “HS2’s activities are all out of synchronism – we must form a new baseline programme.”

Will construction work cease while Wild and his team pore over the figures? No. But wait, didn’t he say everything was out of sync? He did. It does not make sense.

But then, where HS2 is concerned, not much has ever made sense. So blighted is the project that it’s become a scar on the nation’s soul, those two letters and a number, a byword for colossal mismanagement and grotesque financial waste.

While Wild and his colleagues get out their magnifying glasses, work will continue on a £100m bat shed to protect a colony of bats on a 1km section of the route. This, despite the HS2 chair, Sir Jon Thompson, describing it as a “blot on the landscape” and saying there was “no evidence” the bats were at risk from the trains.

Thompson announced this week he will be leaving his role in the spring. Wild told MPs the shed is a “considerable engineering structure… [and] it’s our job to mitigate harm to protected species. It’s the most appropriate scheme and it’s built for 120 years. It’s a complex issue.”

So, no fundamental reset where the bat shed is concerned. At this rate, it will be finished well before the rest of the line. As for the 120 years, there must be the distinct possibility no trains will be running before then, such is the glacial pace of HS2 to date.

The creation of HS2 was announced in January 2009 as a service between London and Birmingham. Soon, extensions were added to Scotland, Liverpool, Manchester and Leeds. There was the prospect, too, of links to Heathrow, Crossrail, the Great Western line to Bristol and Wales, and the Channel Tunnel Rail Link or HS1. Truly, Britain’s transport map was to be redrawn in a way not seen since the Victorian era. The country was to receive a network fit for the 21st century, the equal of similar developments in France, Germany and Spain.

In October 2023, with some experts putting the final cost at £130bn, the prime minister Rishi Sunak proclaimed his own reset: HS2 was to be drastically reduced, so out went the track beyond Birmingham. Now, barely 12 months later, there’s to be a “fundamental” reset.

In the middle, there have been rows galore: about the location of the London terminal (at Euston or to the west, at Old Oak Common); about a hub for the North West at Crewe; about the blight to Buckinghamshire countryside; about the army of consultants employed; not to mention the bats and their shed. On it goes, a never-ending saga of planning battles (the bats being just one of 8,000 or more consents that must be obtained on even the shortened line), disarray and incompetence.

Also this week, MPs were informed by the Department for Transport’s top civil servant, Bernadette Kelly, that she did not “currently have an agreed cost estimate now for phase one [London to Birmingham]”.

An update was provided, of £54bn-66bn in 2019 prices – which equates to £67bn-82bn at current prices – but Kelly said her officials did not “regard it as a reliable and agreed cost estimate”. She admitted this was “unacceptable” but “with great regret, that is the situation”. To think, the entire scheme, including the northern extensions, was allocated £56bn in 2015.

Behind it all is another controversy – more fundamental, to use that Whitehall description again – which is whether HS2 was ever necessary in the first place. Could that money have been, and still be, better spent elsewhere? The short answer is yes.

In 2009, it was conceived as solving the problem of capacity on the West Coast main line from Euston. It was forecast to be at full capacity by 2025. More trains were needed, longer ones too, with increased seating. With that ambition came the desire for speed, to reflect modern expectations and to match European rivals.

But those nations have relatively empty interiors and land is cheap. Britain is overcrowded, certainly in the segment under consideration, and property is expensive. Plus, it is criss-crossed by rivers, valleys and hills. To that could be added a risk-averse culture in government that tried to put the onus on suppliers.

Our politicians loved the fanfare of the big launch but their reluctance to pass something on, for successors to take the credit, is marked. HS2 was never going to be the quick fix that they wanted; Britain’s inability to think long term on mega-projects is a recurring problem. The media switches from praising to picking holes, and the ambition deflates.

There was a further issue with HS2: the North of England never asked for it. There was plenty of protest when Sunak cut the extensions, because it was seen as an anti-North move from an administration that was supposed to be “levelling up”. But really there were no collective Northern voices calling for it, not from the outset. There was much talk of the need for better public transport but that was more to do with adding to trans-Pennine routes in roads and rail, boosting the regional networks between the major conurbations, and the suburban services. They wished for what they see London and the South East having: a joined-up framework of buses, trains and roads.

When it came to discussing funding, the North was crying out for greater digital access (where speed actually is vital) as well as better hospitals, school facilities, housing stock… “levelling up”, in other words.

We are left instead with a railway that even those working on it have no idea what it will cost. Perhaps the reset should be even more fundamental whatever Wild has in mind. HS2 is a symbol of inertia in a nation that gave the world railways, suspension bridges, steam trains, the jet engine, internet and other engineering and scientific marvels but which has ground, literally, to a halt.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments