The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

How George Osborne and David Cameron lost the election for Theresa May

And no, it wasn't by gleefully attacking the Prime Minister in the pages of the Evening Standard...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.George Osborne, David Cameron and Nick Clegg inadvertently helped Theresa May lose her parliamentary majority when they signed the coalition agreement between the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats in 2010.

This led to May’s decision to hold the unusually long seven-week election campaign, which in turn contributed to disaster. If she had gone for a quick election after a four or five-week campaign, she might have held on to her majority.

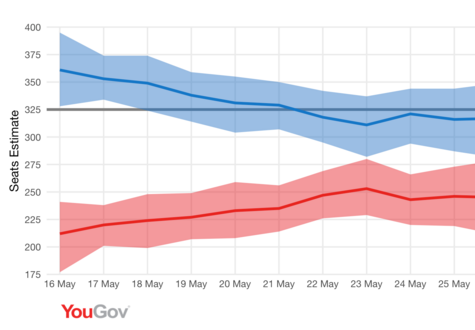

The YouGov model, which turned out to be more accurate than most of the opinion polls, suggested that the Conservatives were still heading for a majority of about 50 on 18 May, four weeks after the election was called. (The grey line on the graph below shows the 326 seats needed for a majority.)

As it was, the Tory manifesto was not published until 18 May. If the campaign had been shorter, it would have been published earlier and might still have had the same disastrous effect. But, given that May ended up only four seats short of a working majority, a shorter campaign could have made all the difference.

So why did May opt for a seven-week campaign? The answer goes back to that 2010 coalition deal. The Fixed-term Parliaments Act was passed by the coalition government to underpin its stability by making hard for either party to bring the government down and force another election.

That was why, after May announced on 18 April her intention to hold an election on 8 June, there had to be a vote in the House of Commons to agree the date – with a requirement that two thirds of MPs had to vote in favour. That meant 436 MPs had to vote for it, so May needed Jeremy Corbyn’s support – which, to some people’s surprise, was forthcoming within an hour of her statement. In the end, the vote was carried by 522 votes to 13.

I can reveal, however, that May thought Corbyn would refuse to vote for an early election. She thought he would tell his MPs to abstain, which would have stopped her because the Act requires two thirds of all MPs, not just two thirds of those voting.

She expected Corbyn to say something like: “I’m happy to have an election, but May is doing this for her own purposes and it is her mess to fix. We can have a vote of no confidence if she thinks the Government can’t govern.”

That was why she had drawn up a Plan B, to pass a short Bill to set the date of the election for 8 June. This would have amended the Fixed-term Parliaments Act, and would have required a simple majority in both Houses. It would have been interesting to see whether the House of Lords would have passed it: May’s calculation was that the peers would hold back from defying a Prime Minister who wanted to put her programme to a democratic vote.

In any case it would have taken time for both Houses to pass the Bill, which was why she had to set the election date so far into the future.

Thus it was that Osborne, Cameron and Clegg ensured May’s defeat. When May called the election, it was said that the Fixed-term Parliaments Act had failed in its aim of curtailing the Prime Minister’s power. As it turned out, it may have been the Act that sealed May’s fate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments