I gave up my film career and moved city to get away from Harvey Weinstein – but he still haunts me

As one of dozens of the film producer’s assault victims, I went into shock when I heard that his rape conviction – a cornerstone of the MeToo movement – had been overturned, says Caitlin Dulany. But it is a reminder of how hard it is for survivors to be believed, to get the justice we deserve – and why we’re never giving up

Last Thursday, I woke up in my home in Los Angeles to a phone full of messages from friends, all asking the same thing: Have you heard the news about Harvey Weinstein?

For a moment, I thought he must have been found dead in jail. There were so many texts, and a survivors group I had been in with a dozen others had suddenly come back to life.

The truth was harder for my brain to register – that a 2020 rape conviction had been overturned on a technicality.

I noticed my hands were trembling and my heart was racing. I was in shock. I still am. I haven’t got to anger and outrage yet, but I know they’re in there. I just I don’t want them to overwhelm me.

Such feelings took me back to that autumn morning in 2017 when allegations about Weinstein first made it into The New York Times. Again, I was in LA when my sister texted me that morning’s front page, and a big picture of his face loomed up on my phone, with a headline about sexual assaults involving numerous women in Hollywood dating back decades.

I remember freezing on the spot, unable to process what was happening. I was blindsided again this month, at news that one of his trials had been declared unsafe and that he would be tried again.

I had met Weinstein in New York, in the winter of 1996. I was a young actress in my twenties, doing a reading of a friend’s screenplay at the Miramax offices in TriBeCa. I was standing outside, eating a burrito, when he walked past. I remember him looking around, circling back to talk to me, and being friendly and very ‘industry’. I felt flattered. He invited me to a screening, at which he introduced me to people as his ‘new friend’, and asked my opinion of the film. At the time, it made me feel special – but it soon became clear he was grooming me.

There was an incident in my apartment, which at the time I brushed off as a one-off. I convinced myself this was a situation I could manage. It was at the Cannes Film Festival later that year, when I was promoting an independent film I was in, that I ran into him again. He invited me to a series of events, which I went to as friends. It was only when I ended up at what I thought was an after party that he assaulted me.

Like many survivors, I told myself this didn’t just happen, or that it was my fault. I didn’t want anybody to know. I certainly didn’t want to get in trouble. I just wanted to compartmentalise it, not think about it, not tell anybody and just have it go away.

But it completely reshaped my career. In an attempt to diminish what had happened, I moved quickly from New York to Los Angeles. I got used to saying I didn’t want to work in film anyway, just in television. I didn’t want to do anything that was shot in New York. But that meant my dreams of appearing in independent films were gone. I was terrified of working on anything to do with Harvey Weinstein, anything that might involve working in close proximity to him, or even seeing him.

I did forge ahead, but it was very limiting in terms of my ambitions. My life was smaller than it could have been.

At the time The New York Times ran its first Weinstein story, I believed I was the only one he had ever done anything to. But, 20 years later, I realised I had friends who had also been assaulted. When the reports kept coming, I realised Weinstein was obviously a huge industry secret.

I took me about five or six weeks to join the chorus of women in the #MeToo movement. One of the first things that I did was contact Katherine Kendall, who had gone on the record about her story, and who I knew from my New York days. I hadn’t spoken to her for a long time, but we followed each other on Instagram and had a lot of mutual friends.

At this point, I hadn’t yet spoken out and was wondering what to do – and Katherine was very tired by her experience. It’s definitely re-traumatising: I attended Weinstein’s 2022 trial in Los Angeles, when he was convicted for the 2013 rape of an actress at a LA hotel. But when he was brought into the courtroom, I went into some sort of shock.

But the ‘good’ news about the situation was that there were so many of us – more than 100 people have come forward with their experiences – and we had found each other. It meant so much that we each had similar stories and could share them. We wouldn’t be navigating the justice system on our own.

My case wasn’t one of those chosen to be heard in court, but I found a sense of justice in being believed and being supported by survivors. So I felt, ultimately, I was involved, that I played my part. I felt heard. Any chance I could, I stepped up to speak, knowing that whenever there was Harvey Weinstein’s face, there would be four or five survivors telling their stories – and that’s very powerful.

We were part of the group that came to be known as the Silence Breakers. We put out press releases around that original New York trial that put Weinstein away, and we worked hard to make sure survivors’ voices were heard – that it wasn’t just all about him, and what he was going through.

One thing I’ve found is that, when it comes to crimes of a sexual nature, the US justice system is unfair. Bill Cosby had faced hundreds of accusations, but his first trial ended in a mistrial. He was eventually jailed on three counts of sexual assault – but he was released after his conviction was thrown out after a court ruled his rights had been violated.

I was prepared that Weinstein’s trials would expose cracks in the system, but thought that guilty verdicts would show to the world that we were moving forward – in believing survivors, in getting justice.

Three out of the seven judges dissented to reversing Weinstein’s conviction. Judge Madeline Singas has spoken about how the majority opinion perpetuates outdated notions of sexual violence and allows predators to escape accountability – and “because New York’s women deserve better, I dissent”.

And I dissent, too – I think we deserve better. All survivors, all women, deserve better. The overturning of this one conviction, a cornerstone of the MeToo movement, will have consequences, because as a result victims of sexual assaults will be even more reluctant to speak out.

What is so outrageous, and so devastating, is not just that we have to fight Weinstein all over again, we have to do it while up against the justice system, too. Now we’re fighting both at once.

And after all the inroads we thought we were making. It has taught me how legal wins can be undone so quickly and so easily – and the war on women in America is real.

The changes we need to see in our legal system, I want them to happen in my lifetime, and I’m never going to stop advocating for them.

So I will be in that courtroom for Weinstein’s retrial. I’ve done it before. This time, I’ll be even stronger. We all will be. We’re not going to let him get away with it.

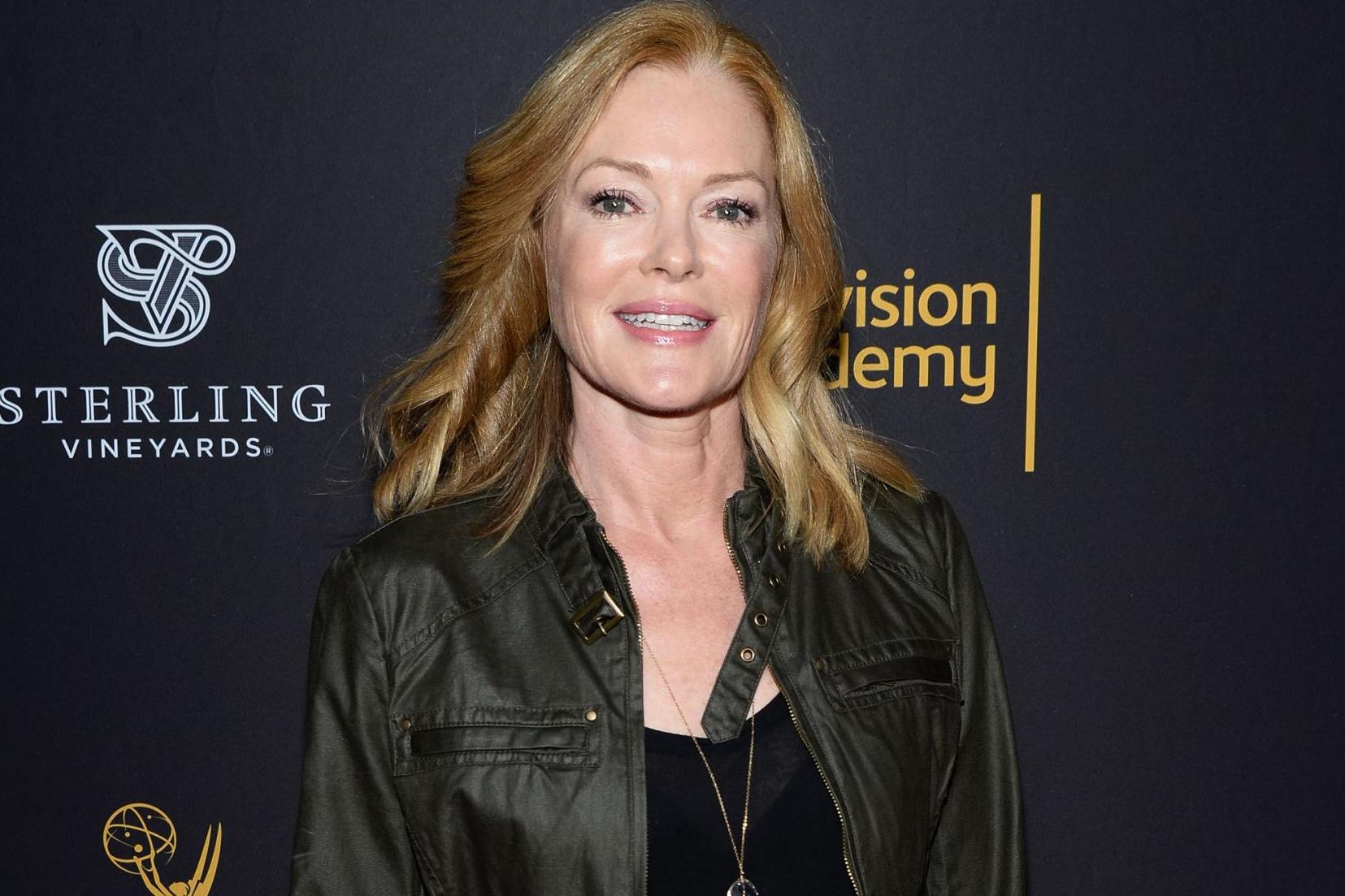

Caitlin Dulany is an actress based in California

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments