What it’s like to suffer from haemochromatosis, the Celtic disease which is more common than you think

Despite the fact 5,000 people in Dublin alone suffer from the condition, doctors have told me they know barely anything about it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was the summer of 1987. I had just returned from a two year stint in Saudi Arabia with my family and I had a three-year-old toddler who was like Speedy Gonzales, constantly on the move. I had been feeling very tired for months, but I put it down to living in intense heat and having an active child.

Then my sister got diagnosed with a rare disease called hereditary haemochromatosis (HH). As you can probably guess by the name, it’s a genetic illness – and when she was told by her doctors that she had it, she was also advised to tell all of her other siblings to get tested. Each of us had a 50 per cent chance of inheriting the same condition – and I won the medal.

Put simply, haemochromatosis is a disorder caused by an accumulation of iron, almost like the opposite of anaemia. People who have haemochromatosis absorb much more iron from food than other people due to a faulty gene, and it builds up in levels the body finds it difficult to deal with. Iron overload causes pain, tiredness and damage to the liver and heart.

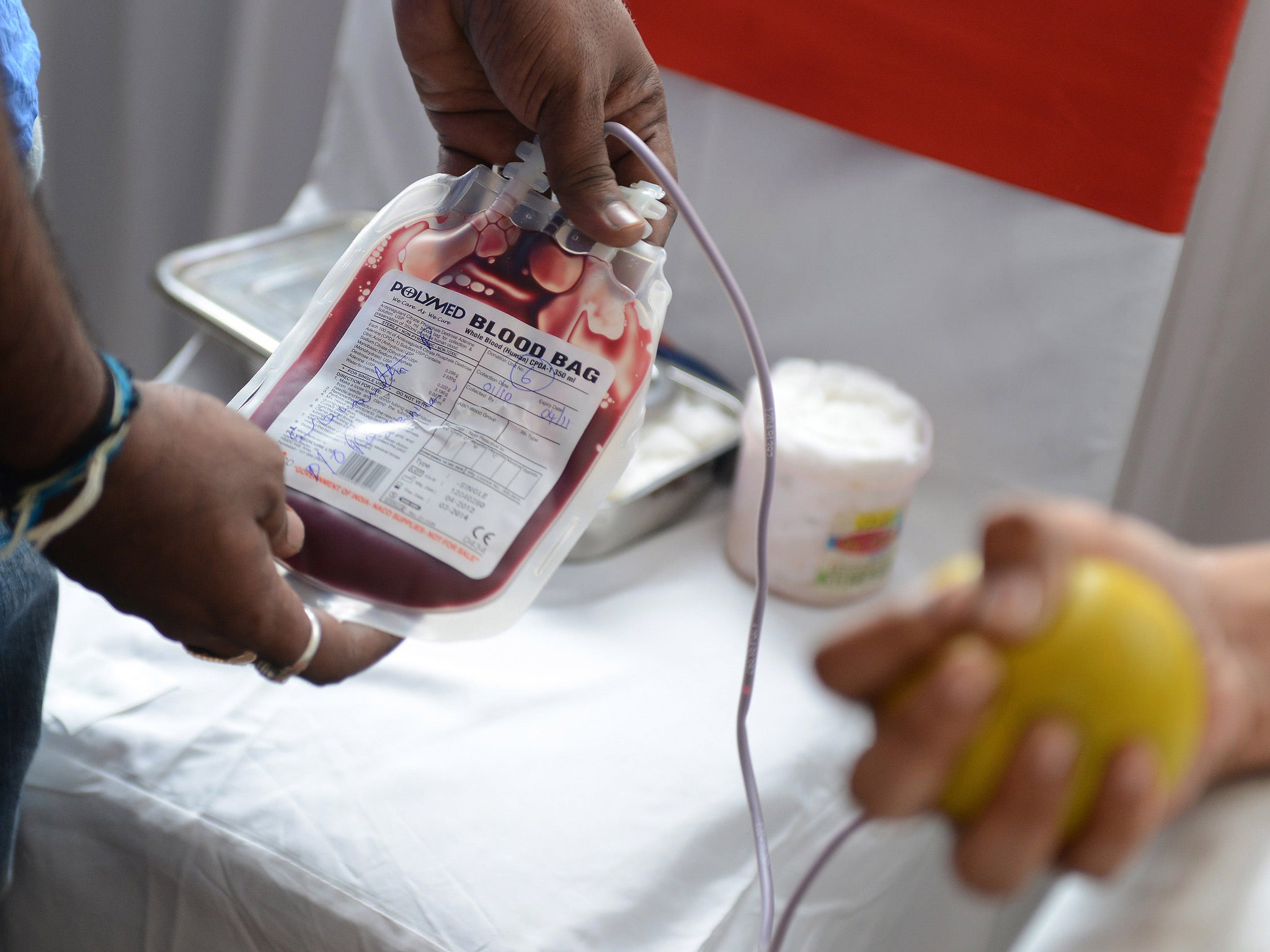

The consultant who I first met about my condition told me if I didn’t have regular phlebotomies – basically procedures where doctors drain some of your blood specifically to lower the iron overload in your body – then my lifestyle would deteriorate significantly after 10 years, and I would most likely be dead before 20 years were up. I have a major needle phobia and don’t relish having the things stuck into me on a regular basis, but at that point I had very little choice.

It was expected I would have a pint of blood drained off every week in the same way a blood donor would give a pint annually – except my blood would be destroyed rather than donated. This procedure is the only way to manage HH and to balance out my iron levels. But after a while, it became clear my body couldn’t cope with the shock of it: I would get very weak and faint sometimes while it was happening.

So instead I did the procedure every two weeks, and took a day off to go up to the hospital for it (luckily I had an understanding boss). Thirty years ago things weren’t quite as sophisticated as they are now, and all the checks and tests took much longer.

In 1990 I was asked, along with my sister, to form a support group for people like ourselves, and so the Irish Haemochromatosis Association was started. The main aim of the association was to get HH recognised, to fundraise for research into the disease and to support likeminded people. HH is a Celtic disease which has become a worldwide problem because of immigration. It is thought that one in nine people of Celtic origin are carriers of the mutation and one in 200 has it. It’s worth bearing in mind that it’s easily treatable if it’s detected early.

Because of the association, I ended up doing a few media appearances and radio shows to raise awareness. At one of the radio interviews there was a GP present to give the medical slant on proceedings. Before the actual interview, he quizzed me on HH as his own knowledge of the subject was almost nonexistent. He showed me the only paragraph he could find in all his medical books. There was no information as to how one got HH, how to treat it, what the side effects were and whether or not it could be avoided.

For this reason, educating the medical profession and in particular GPs became paramount. This was not an easy task. Many doctors were as unaware of the disease as the doctor I’d met on the radio programme that day. As a matter of fact my own GP, who had a very big practice, told me that for years I was his only diagnosed patient.

Today there are approximately 5,000 people diagnosed with HH in Dublin alone – so HH is not as rare as you might think. HH screening has become more or less the norm for medicals but recognition of the condition as a chronic disease – which would get much-needed government funding for things like research and treatment plans – has yet to be realised.

The major concern now is to have HH recognised as a disease for life so regular phlebotomies can be done free of charge. At present, unless a patient has a medical card or private health insurance, the charge is €80 (£70) per session. If blood is taken off four times in a month, which is usually what’s needed, that adds up to €320. That’s an unacceptable financial burden on someone who has a genetic condition they can’t affect.

HH hasn’t held me back – I’m a 72-year-old young lady who looks 60 and lives a full life – but if I went undiagnosed I’d be pushing up the daisies by now. I avoid any food with fortified iron and don’t take multivitamins. By choice I drink virtually no alcohol and so I’m always the designated driver.

The main thing I would say to people is that if you have northern European ancestry – especially Irish – then it’s worth getting checked if you have the symptoms of weakness, tiredness, weight loss and joint pain. The disease is surprisingly common, so it doesn’t hurt to be aware.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments