Government must look again at pay and conditions to tackle teaching recruitment crisis

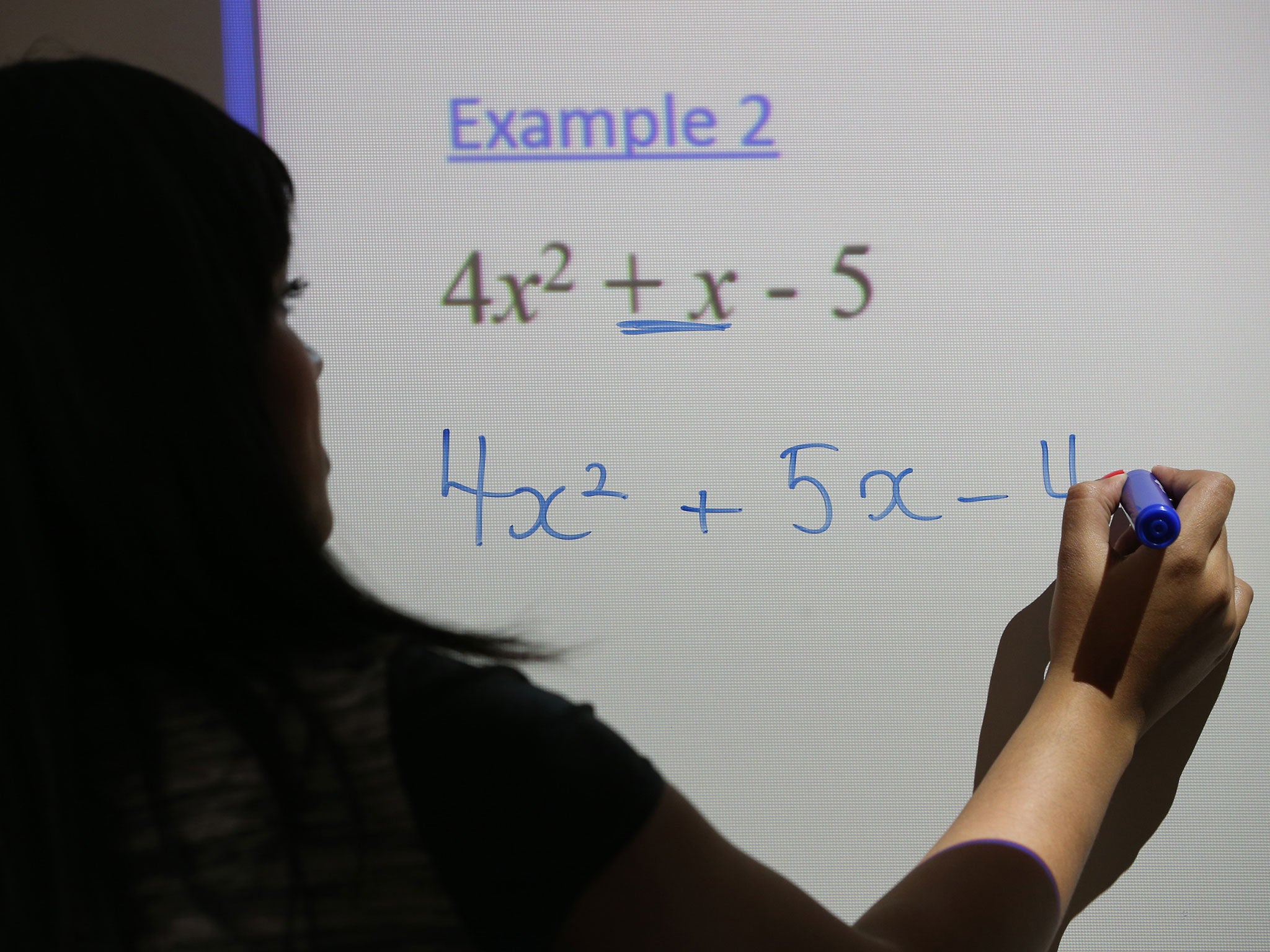

Attracting people teaching requires demonstrating it is a profession marked by creativity, problem solving and passion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It offers a steady career path, job availability in every part of the country and approximately 13 weeks of paid holiday a year – so why are so few people willing to become maths teachers? Or, for that matter, science, history, English or geography teachers?

Schools are struggling to recruit specialists – from physicists to linguists to masters of algebra – who teach our children the skills they need to flourish. A survey of 900 headteachers in secondary schools across the UK found that the vast majority cannot fill vacancies in core subject areas, and that the situation is getting worse year by year.

Teacher shortages are growing because secondary teacher training places are going unfilled. Just as significantly, the inability to find teachers to replace those who resign or retire is putting extra pressure on a profession already dogged by stress and overwork, owing to constant government intervention and the relentless drive to raise standards in an environment where resources are always limited.

Many of the solutions dreamt up by teachers to tackle the problem, such as merging classes, have fringe benefits. For example, bringing children together into large groups is a feature of a new trend in education known as “modern learning environments”, designed to offer teaching tailored to each child’s own learning style. But if the end result is simply larger classes with no additional teachers available then those potential benefits would be wiped out.

The stripping of specialist knowledge from secondary schools is also a cause for serious concern. Heads report that teachers trained in other subjects are now forced to step in to teach Year 11 pupils mathematics – a critical year in which only a deep understanding of the material being communicated leads to confident pupils able to obtain a C or above at GCSE maths, unlocking the doors to further and higher education. There are two areas in which the Government could take immediate action to prevent the recruitment crisis escalating. One is to review how teachers are paid, and whether extra benefits should be available to specialists in certain subjects.

The average secondary classroom teacher starts on a wage of about £22,000, rising to £33,000 with experience; in an economy deficient in science, technology, engineering and mathematics graduates, those with the necessary talent are tempted away into other more lucrative professions. Teachers’ pay still lags behind other public sector professionals with equal expertise and responsibility; it is time to put that right.

Government should also consider the burdens it is placing upon teaching as a profession. According to several studies carried out by teachers’ unions over recent years, almost three-quarters of teachers say their job has a negative impact on their well-being – a figure that is remarkably consistent across surveys. The more stress teachers are under – a problem which is only exacerbated by teacher shortages – the more likely they will leave the profession, and the fewer people who will apply to join it.

Finally, school heads should think hard about how they might be able to tackle the problem. One option is to consider paying additional staff or supplementing salaries in “in-demand” subject areas from income raised by use of their own assets. Allan Foulds, president of the Association of School and College Leaders, which carried out the survey, reports that he has earned enough to pay three teachers from the leasing out of sports facilities at his school.

There will be many more examples of such opportunities. Attracting new graduates and career changers into teaching will require demonstrating it is a profession marked by creativity and problem solving, as well as passion.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments