My Soviet refugee parents had their lives changed by Gorbachev

‘We started seeing color when Gorbachev became president’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When I heard former Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev had died, an oft-repeated phrase of my mother’s came to mind. “Our life was black and white before 1991” – the year when the USSR collapsed – she used to tell us (and still does). As the first-generation American child of Soviet Union refugees, I have no affection for a Soviet president. But I do appreciate the opportunities that my family was given by Gorbachev’s policies.

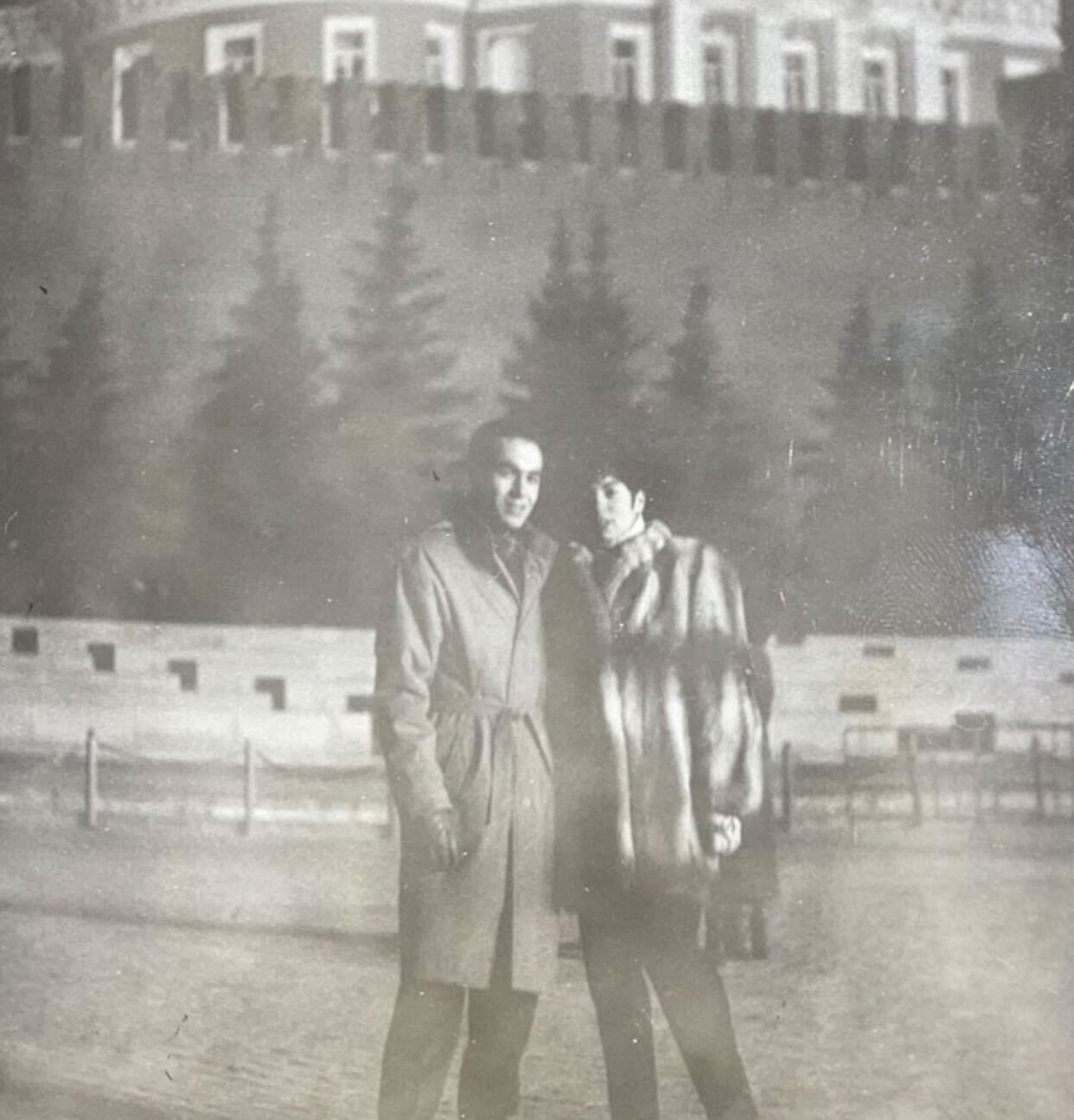

My parents were teenagers when Gorbachev first came to power as the first, and only, president of the USSR. My mother attended a Revolution Day celebration in Moscow during her first year as a university student. She recalls seeing Gorbachev as he stood atop a Red Square tribune, waving at the crowd with a smile.

“Soviet politicians didn’t usually smile like that, publicly,” she told me. For the first time in all her life, she felt hopeful for the future.

Only a few years prior, my mother had been in history class at school when she’d come across an article about the conditions political prisoners faced in Russia in the 1930s. She asked her teacher about it, and recalls her teacher’s face turning pale. She told my mother to “be quiet” and wouldn’t say any more. Teachers could lose their careers for discussing such topics in the classroom.

This conversation took place as Gorbachev first began implementing his policies of glasnost and perestroika, meaning “openness” and “reform”. It was a new direction for the Soviet Union, and a positive shift for the citizens who lived in it. Nevertheless, people like my mother’s teacher were clearly still traumatized by years of political oppression.

Growing up, my parents listened to the “Voice of America” radio station under the covers late at night, hoping to get snippets of alternative information. They lent and borrowed previously banned books among their friend groups, eager to consume media from abroad.

The last few years of Gorbachev’s premiership marked a time of stark contrast and uncertainty. The general public continued to live in fear of persecution, because that’s how they’d been taught to live. For the first time in decades, though, the dissemination of information in the media was unregulated. New ideas were being openly discussed. New policies were being enacted. And policies had a profound effect on my family’s ability to emigrate to the United States.

In 1990, my parents applied to the USSR for an exit visa, and applied to the US for refugee status on the basis of ethnic and religious persecution. As Soviet Jews, many jobs and educational opportunities had been off-limits for them. Even class rosters in schools required teachers to disclose a student’s ethnicity. My father recalls that a teacher who didn’t want him to face problems in school wrote his ethnicity as “Russian” instead of “Jewish” on the class roster. Discrimination came anyway.

Widespread systemic antisemitism continued to exist in the Soviet Union well into Gorbachev’s administration. Now, however, the government was publicly denouncing antisemitism and acknowledging its presence. “The venomous sprouts of antisemitism arose even on Soviet soil,” the Soviet leader said in a 1991 speech in Ukraine. To admit that something bad had happened even inside the USSR was revolutionary, much less that it should be corrected.

Gorbachev’s government lifted travel restrictions and allowed for thousands of Soviet Jews to leave the Soviet Union, spurring a mass migration. Indeed, 400,000 Soviet Jews left the USSR from 1990 to 1991, according to Mark Tolts, a professor at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. My family was a part of that mass exodus.

Every now and then, my mother reminisces about the aster flowers she would stroll by on her walks in Moscow. My father always buys the sunflower oil that reminds him of his childhood summers in Ukraine. He’ll play classic folk songs in the car that he once played on the guitar while camping with his friends in the Caucasus Mountains. My parents miss the walks down the city boulevards they once had memorized, and their dear friends they once saw every week.

But they are happy to reminisce from a distance. Looking back on life in the Soviet Union is often also largely accompanied with painful recollections of generational trauma and constant fear. The land that gave them their culture and their childhood memories is not what they consider to be home anymore.

My family’s lives changed forever after the fall of the Soviet Union. They gained freedom and the kinds of opportunities they could only have dreamed of inside the USSR.

I called my mom today to talk about the news of Gorbachev’s death. She said her old, familiar phrase, and then she followed up with: “We started seeing colour when Gorbachev became president.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments