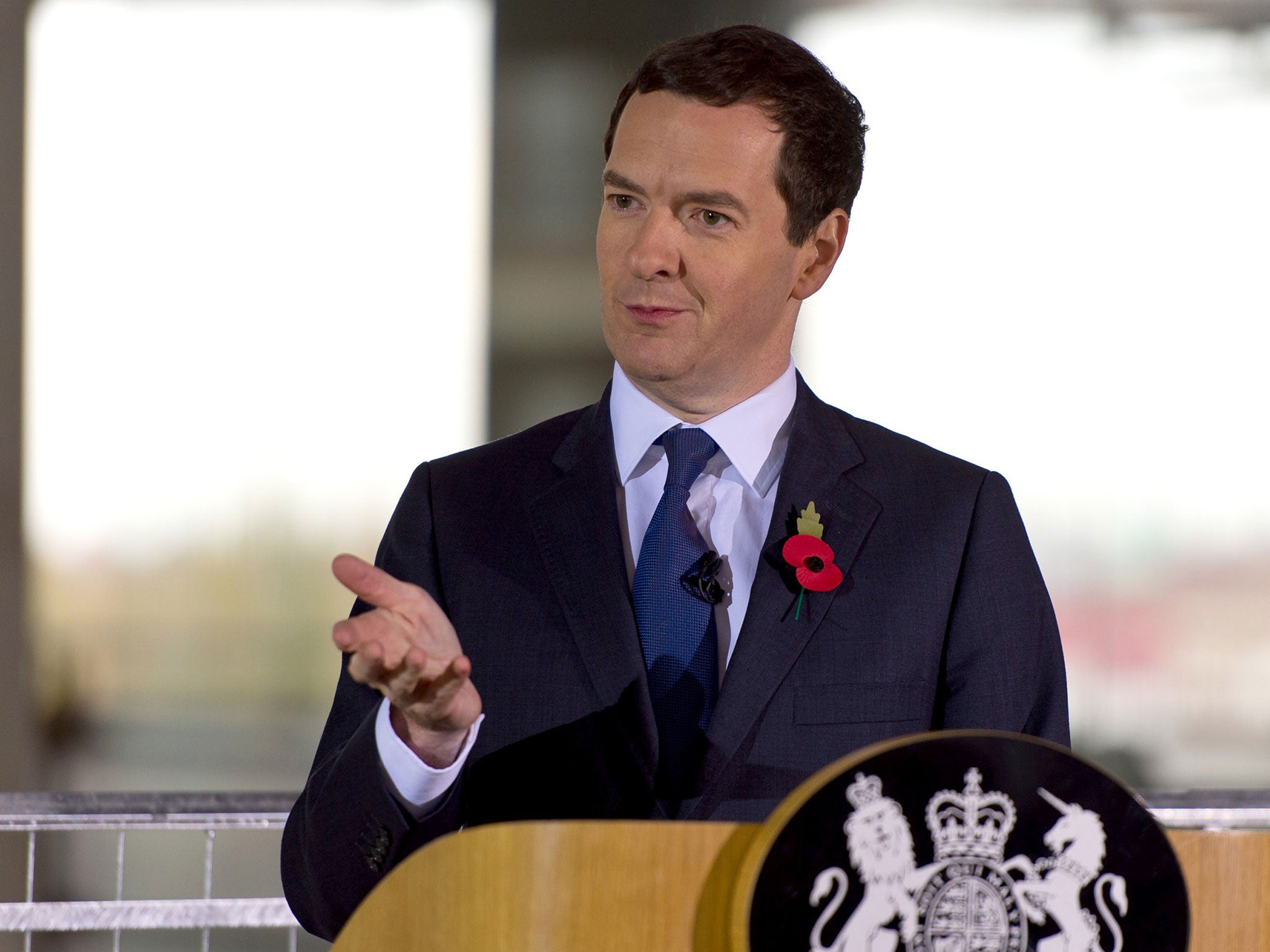

George Osborne needs to prove his cuts won't stall improvements in education

Without better education, England faces the prospect of rising poverty and unacceptable levels of social division

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Two weeks tomorrow, George Osborne will deliver his autumn statement, and there will be particular focus on how he chooses to tackle the problem created by the excessive and rushed cuts to tax credits, which were announced in the recent Budget. The Chancellor may dislike having to bow to the unelected House of Lords, but on this occasion the peers are speaking for the people, and the Government needs to listen.

Anyway, Mr Osborne is surely sensible enough to realise that he erred in proposing to make such large and rapid cuts to the incomes of low paid workers, without giving the opportunity for pay rises and other tax changes to cushion these changes over time.

The short term problem with tax credits ought to be (relatively) easy to fix. The greater challenge will be to make a reality of the new life chances agenda – which rightly focuses on moving from tackling poverty through welfare payments, towards giving people the tools to make a success of their own lives. Without a successful education system and more highly paid employment, there is a serious risk that the cuts to benefits will drive big increases in poverty for both children and adults of working age, over the next five years.

Mr Osborne and Mr Cameron now need to demonstrate that their refusal to sign up to child poverty targets was about more than a knowledge that their own policies were likely to drive measured poverty rates much higher.

The Government now needs to set out a long term agenda which demonstrates that its rhetoric about creating real opportunity is backed up by substantive policies.

Part of the test will be for the Chancellor to avoid any further erosion of work incentives. Universal Credit (UC) has been a costly and complex project which can only be justified if it really does help make work pay. The Treasury keeps salami-slicing the UC budget, in ways that are usually not easily visible, but if there are further significant cuts then we could end up in the unfortunate situation of having subverted the entire point of the programme. Mr Duncan-Smith is right to look on with concern.

The Government also needs a new drive to raise educational standards, and to keep the focus on improving attainment for young people from disadvantaged backgrounds – those who are much more likely to end up in poverty and on benefits. We are not going to address poverty and create opportunity while 60 per cent of young people from poor households fail even to achieve the old and unambitious target to secure five GCSEs at C grade or higher, including English and Maths. This figure is a national disgrace.

The last Government had a strong record on education – with the introduction of the Pupil Premium, swift action to tackle failing schools, and the clean- up of English’s discredited qualifications system. But there is nothing at all to be complacent about. If the country’s main anti-poverty and pro-opportunity strategy is now to rely on education and work, then we have got to do an awful lot more and more intelligently

And there are now significant risks of educational improvement stalling. The Government’s new 30 hour childcare offer deliberately excludes some of our most disadvantaged children, who need relatively more help, of higher quality, and not less. Under the Government’s plan, the poorest children will only receive half of the early years entitlement of the rich. What sense does this make, if boosting opportunity for all is the aim?

And there are other issues. While some academies are doing quite brilliantly, as many as a third are not doing well enough, and we have a shortage of new, quality, sponsors.

The Coalition Government protected real schools spending, but that protection has now been removed – which will make it more difficult to recruit and retain teachers, as we face what could be a serious recruitment crunch.

We now need a new drive to raise the country’s educational ambitions, improve the quality of early years education, attract and retain good teachers and develop the next generation of leaders, ensure that academies policy is driven by a focus on quality and not just numbers, and do more to spread outstanding practice from 4,000 schools to all 24,000.

On 10 November my own think-tank, CentreForum, embarks upon a new programme of policy work to address these challenges. As Mr Osborne looks beyond his autumn statement, he and the Prime Minister urgently need to address these issues too. Without better education, England faces the prospect of rising poverty and unacceptable levels of dependency and social division. Fixing tax credits is not nearly enough.

David Laws is executive chairman of the CentreForum think tank. He was Liberal Democrat MP for Yeovil from 2001-2015 and was Schools Minister from 2012-2015.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments