One of the worst things about Generation Rent? I moved house – and had to get rid of 600 books

For literature lover Rob Palk, the unthinkable happened – but how did ditching all those novels help to reignite his love of reading?

A few weeks ago, I sold most of my collection of 700 books.

I had just been evicted. My room was in a shared house that had been allowed to revert to a pre-human state. There were edible-looking mushrooms growing in the bath, the walls had a light coating of blackish mould, animal infestations would flourish then suddenly vanish, as though the mice and insects had given up.

Local eccentrics moved in. And then departed in a hurry. One housemate left hidden tape recorders around the building in case we were talking about him. Another used to cook soup then air it outside in its pan overnight.

I won’t miss it, but it was cheap. It was home.

In my hunt for alternative accommodation, I soon realised two things: I would be paying more; and I would have less space. I started to look at my book collection with uneasy eyes.

From the age of about six, books had been my identity. I was the silent kid in the playground squinting at a copy of The Hobbit or Charlie and the Chocolate Factory or The Sword in the Stone. The addiction lapsed briefly in my teens with the discovery of pop music, but then came back around sixth form, when I decided reading the heftier classics would impress girls. If this ever worked, none of them mentioned it. Still, I posed with Dostoevsky, with Eliot or Joyce and eventually I wasn’t posing any more. Eventually I just loved this stuff.

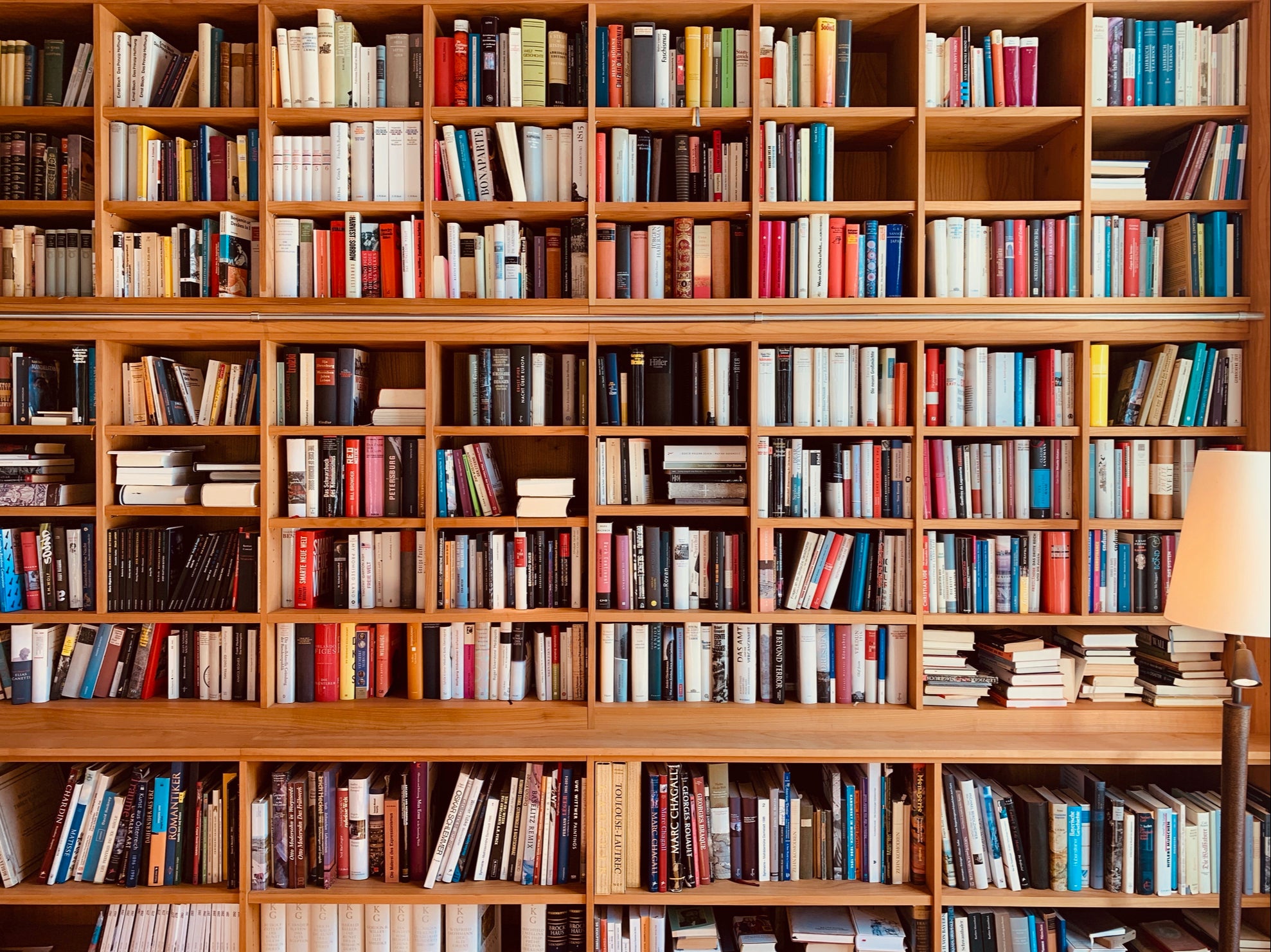

Skip forward 20 years and I can no longer clean my room without dislodging a tower of paperbacks. They loom along the walls, collecting dust. They are literally propping up my bed, which has otherwise collapsed. My shelves are buckling under them.

I don’t think I am a hoarder, but my test is always, “Might I read this again?” Very often, I might. Only now they seemed to be breeding, proliferating, swallowing my space. I’d visit potential new rooms and picture them crammed with novels, through which I’d burrow to my bed. The books would have to go.

I allowed for some exceptions. Books I’d not read were spared, as were any signed by the author. I whittled them down to two boxes. Otherwise, everything went; the fat classics and slim contemporaries, the great Russians and the Victorians, the modernists, the post-modernists, the not-at-all-modernists.

Each book held a double story: the one it actually contained, and the story of my ownership. This one accompanied me on holiday, its pages still smeared with sun lotion and sand. This one had a battered spine from repeated teenage re-readings. This one was urged upon me by a partner and brought back old conversations, exchanges of ideas. I wasn’t sure digital copies would hold the same charge.

Back when I started writing and collecting books, I had an expectation my circumstances would somehow match my reading. A well-read person would be successful, they would have somewhere to put their books, a gentleman’s well-stocked library.

If this had ever been true, it wasn’t any more. Cultural capital had no link to material rewards. Insecure rental properties and unwelcome moves meant that a book collection was no longer something I could practically have. I had a rich literary hinterland and nowhere to put it.

I began piling volumes in boxes ready for sale. I wasn’t just leaving a house, but leaving behind the first half of my life. From now on, I’d live unencumbered by print. There was something exciting about saying goodbye to them, a feeling I was embracing the future. Still, when the collection was finally gathered in 10 large boxes ready for sale, I found that I was crying.

I’d never been sentimental about books as objects – never been the sort of person who smells the pages or tracks down first editions. Only now I would never see these copies again, I worried I was making a mistake. These dusty paperbacks were a record of my life. They had a power beyond their contents.

I steeled myself. The books were collected, money changed hands and I moved to another room.

A friend gave me their old Kindle and I went to Project Gutenberg and stocked it with classics. Works from the last 100 years would be added more slowly, in attritional bursts.

I decided to reread Howard’s End, a book I had always loved. It contains a character named Leonard Bast, an autodidact, who has no money but yearns for literature; a world of culture from which he is excluded by his class and his prospects. Books mean more to him than to those who have large rooms in which to house them. They mean an escape, a lifeline – and in a brutal irony, he is eventually killed by a toppling bookcase.

I soon forgot I wasn’t reading my old Penguin Classic edition. I was transported, as I always was. It wasn’t the books that mattered. It was the words in them, all along.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments