If GCSEs really are an ‘accurate measure of future success’, that’s exactly why we need to get rid of them

A new study asserts your exam results will tell you how well you’ll do later in life. Former teacher Ryan Coogan (who messed up his exams) says there are far better ways to predict someone’s future than that

My favourite thing about exam season is when, on the day students are queueing up to receive their GCSE and A-level results, every op-ed columnist and internet commenter in the country races to be the first person to declare “well, I failed all my exams and I turned out fine!” Bonus point if, as is often the case, the person commenting did not in fact turn out fine.

That being said, I have a confession to make: I did really badly in my GCSEs and my A-levels, and I really did turn out fine.

How badly did I do? Well, badly enough that I had to do an extra year of A-levels so I could get into university. Badly enough that I had to play catch-up during my degree because I was behind everybody else, even though I was a year older than them. As for how fine I turned out… well, that’s relative. But I am (humbly) pretty proud of where I ended up.

My experience appears to be a bit of an outlier, though, as new research published in the journal Developmental Psychology has found that GCSE results are an excellent indicator of future success, faring better than other factors such as gender – and even university grades.

“What we can definitely say is that GCSEs have a considerable impact on how your life develops into your early twenties, and that the benefits from GCSEs are over and above the education someone obtains later,” says researcher Alexandra Starr, who co-authored the study. “The main message I would say is that GCSE grades are important in real life. We always talk about whether exams are only important within the education system, to climb the next rung in the educational ladder. But it’s also important beyond that.”

Let’s ignore the fact that the study about exam attainment was literally written by a Ms A Starr, and get down to brass tacks. I won’t argue with the results of the study – I’m not a sociologist, and I’m sure these researchers know a lot more about the field of child development than I do – but the narrative it reinforces does require some scrutiny.

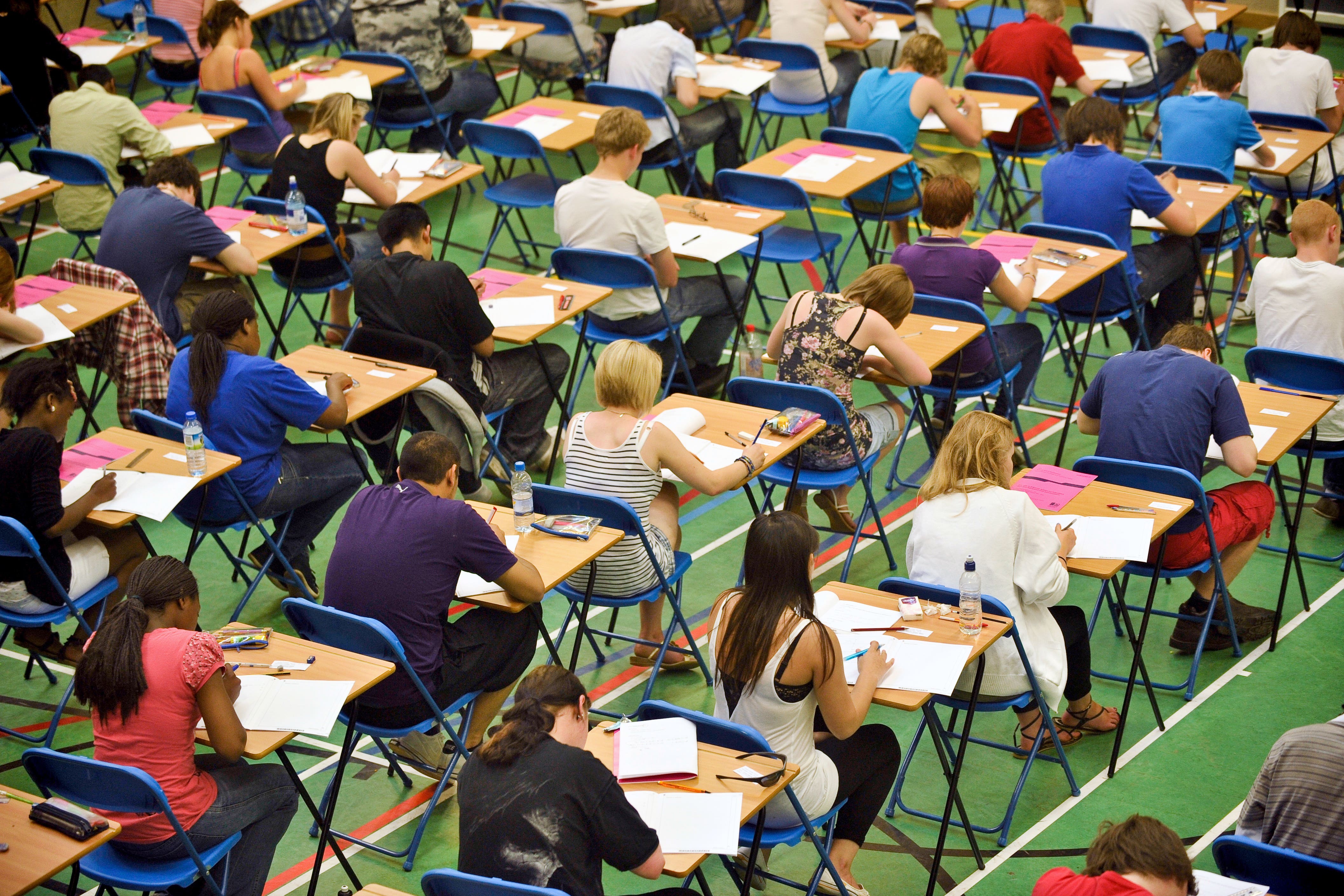

There’s something very insidious about the fact that we put so much stock in a series of exams that we force kids to sit before they’re legally old enough to buy fireworks – and I say this as a former high school and university teacher. Sixteen-year-olds are barely able to conceive of a future beyond next week, but we tell them that the grades they get right now – at a time in their life when they are at their most contrarian, volatile and vulnerable – are going to map out their entire futures forever and into eternity.

For me, things worked out very differently. I was a terrible student through most of high school and college, but the second I reached university, where I was able to focus on the things I was good at without academic and situational distractions, I immediately started to do extremely well, to the point that I eventually went on to do a master’s degree, and later a PhD. Other people I knew had the completely opposite experience – incredible grades all through their formative years, then completely burnt out by the time university came around.

I also find it interesting that one of the study’s findings was that GCSE grades were an especially good predictor of success for students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Again, it’s the sort of thing that seems obvious, but I’d have to wonder what counts as “disadvantaged” in this case. Growing up I knew plenty of people who identified as working class, but whose circumstances could not have been more different to my own.

Little things can make a huge difference in somebody’s working-class experience – living with both parents, living in the “good part” of a bad area, the presence or absence of addiction or mental health issues in a household – but they seem to rarely be taken into account when it comes to studies like this. In my experience, the kids who did well in my (comprehensive, very working class) school were the ones who had one parent in the slightly higher income bracket, or who only attended my school because they happened to be on the boundary of my school’s catchment area. To an academic researcher they may be classified as “disadvantaged”, but to me, growing up, they had the exact kind of advantages that put them ahead of the rest of us.

Don’t get me wrong, education can be a huge difference-maker for disadvantaged kids – it certainly was for me – but there’s a difference between education and grading. Whenever I hear somebody say that “good GCSEs are necessary for a good future”, what they’re also saying is that bad GCSEs can condemn you to a life of failure. And that just isn’t true. Or, at least, it shouldn’t be.

I’m not going to come out and say we need to bin exams altogether (although, if I’m being honest, distilling a child’s entire educational development in a 90-minute stress-filled ordeal they’re going to have nightmares about well into their thirties is the kind of strategy that could probably do with a rethink). But we definitely need to change our thinking around them.

We need to start letting kids know that they aren’t a lost cause because they got below-average grades during a period of their lives when they still haven’t even really figured out who they are as people. That there are other avenues open to them, and that they can always pick up the slack. That life doesn’t end in your early twenties (and for some of us, it doesn’t even start until much, much later).

It’s not the worst advice in the world. After all, I got bad grades and I turned out fine.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments