The two simple things that could smash the political class and fix our broken democracy

Concluding his two-part series on mending modern politics, The Independent’s founding editor shares his ideas for a better future

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I described yesterday what Britain’s political class had wrought – an unnecessary referendum, a dishonest debate, a Leave campaign that had no idea what to do following its victory, and a Government that was unprepared.

Some have described the country’s situation today as being the most difficult since the Second World War. People at all levels of society readily reveal their concern at what has happened. There is a high level of foreboding.

I drew attention to the growth of this political class that has encamped itself in the House of Commons. It comprises MPs who have done nothing with their professional lives except politics since their early twenties.

Thus some 40 per cent of today’s Conservative MPs had careers as political advisers, or as research assistants, or as analysts in policy research bodies or as lobbyists before being elected to Parliament. The comparable figure for Labour, including former trades union officials, is 60 per cent.

This political class has no training for government and little aptitude for it. That explains why we so often feel that we are living in a dysfunctional state. Instead the political class is consumed by the day-to-day political battle and how to “position” its leaders for it. I put forward a proposal that would stop membership of the House of Commons being a career for life rather than a satisfying public duty.

This is that MPs should be subject to term limits. This would mean that they would be able to serve for, say, only three sessions of parliament. To put it another way, they could stand for re-election no more than twice. As a result, MPs would have to have had careers outside politics to which they could return.

Term limits are common in presidential systems of government. They are less often found in countries operating a parliamentary system of government. Indeed, there is absolutely no chance that the House of Commons as presently constituted would vote for such a measure. Is there any way round this obstacle?

I think there is. We should to turn to civil society.

What is civil society? It is the space between the state and the market. It comprises a wide variety of voluntary associations devoted to promoting the public good. Many of them are self-help initiatives. The sector includes charities large and small as well as think tanks, trades unions and churches.

The National Trust is part of civil society. So is the Salvation Army, which was founded in the east end of London by a Methodist preacher in 1865 and now spans the world with its shelters for the homeless. Food banks are another example.

But civil society is more than just the kinds of organisations mentioned above. It is also comprises the millions of citizens – like the readers of The Independent – who are prepared to work for the public good when the opportunity presents itself.

When civil society sees a social problem, it does the research and finds a solution. Then it sets up an organisation to promote reform. It raises the necessary funds by seeking private donations.

In one way or another, it gets on with it – a welcome contrast to parts of Whitehall. Here are three examples.

The Howard League for Penal Reform is a membership organisation that has an enormous influence on prison policy while itself employing a staff of little more than 30 people. It campaigns on children in prison, women prisoners, suicide and self-harm, community sentences, prison education, and young offenders. It has also set up student societies that organise events and lectures.

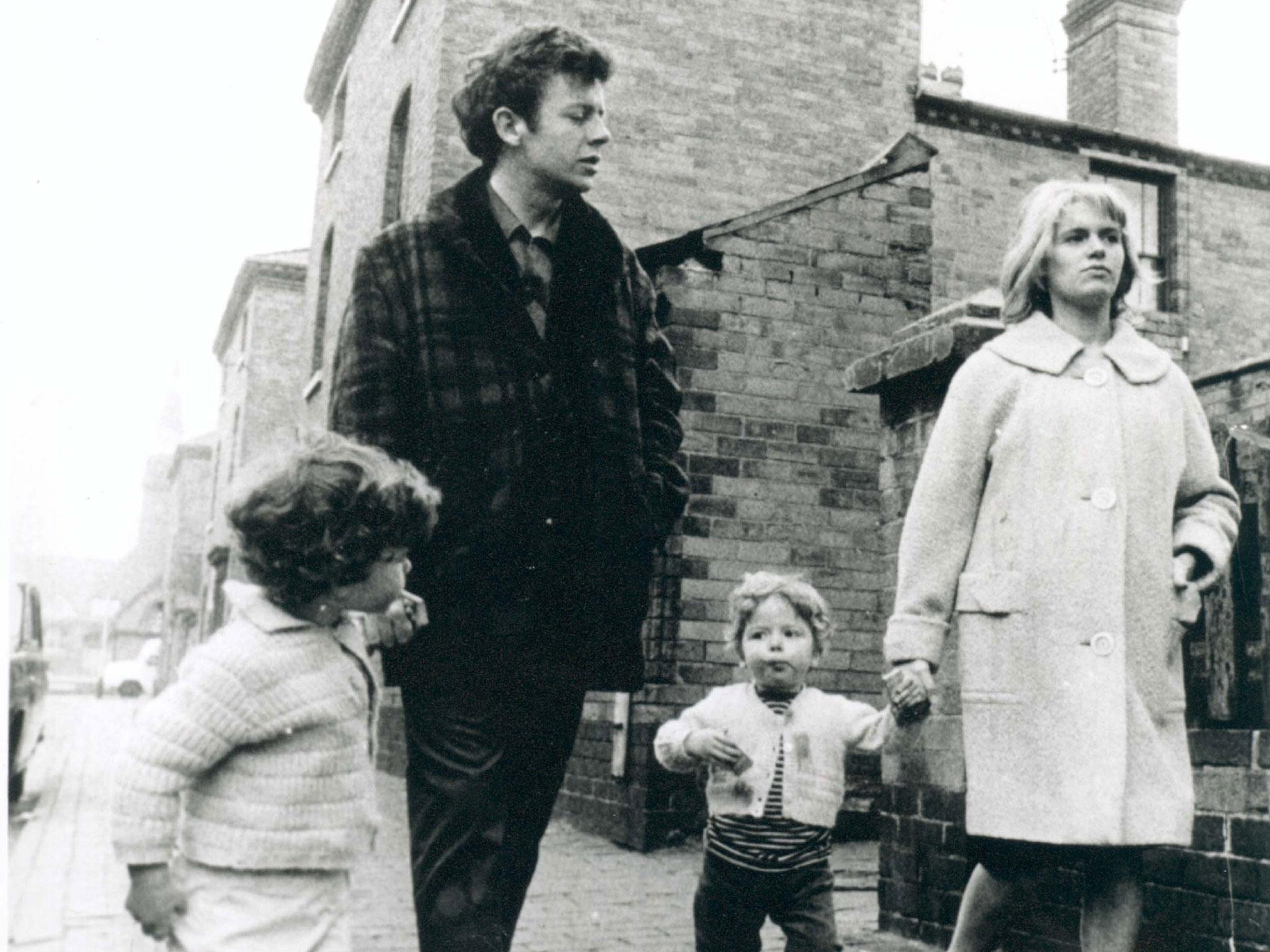

The national charity for single homeless people, Crisis, was founded in 1967 in response to the Ken Loach TV play Cathy Come Home, broadcast the previous year. It offers year-round education, employment, housing and well-being services from centres in London, Newcastle, Oxford, Edinburgh and Merseyside. It campaigns for action to prevent and mitigate homelessness. It raises more than £20m a year from individuals, events, gifts in kind and donated services, and from companies and trusts.

In contrast, the educational philanthropist Sir Peter Lampl founded the Sutton Trust, the educational charity, nearly 20 years ago. It describes itself as a “do tank”, and it commissions regular research to influence policy and to inform its programmes to improve social mobility through education. It is particularly concerned with breaking the link between educational opportunities and family background, and in bringing about a system in which young people are given the chance to prosper, regardless of their family background, school or neighbourhood.

These three impressive initiatives are typical of “civil society”. It is in this area of our national life that I believe we should be able to find the help required to repair our badly working political system.

These are my two hopes. The first is that civil society should start the work of writing some sort of manifesto for the next general election using all its insights and practical experience. I should like the introduction of term limits for MPs to be among the proposals.

And the second is that when this has been done, ordinary members of civil society should be prepared to stand for Parliament as a public duty, probably only for one term, with the hope of carrying out the manifesto recommendations and clearing out the political class.

All this would require an enormous effort, but it could be done.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments