The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

From Felicity Huffman memes to an MP wearing an ankle tag, why does gay Twitter adore 'bad' women?

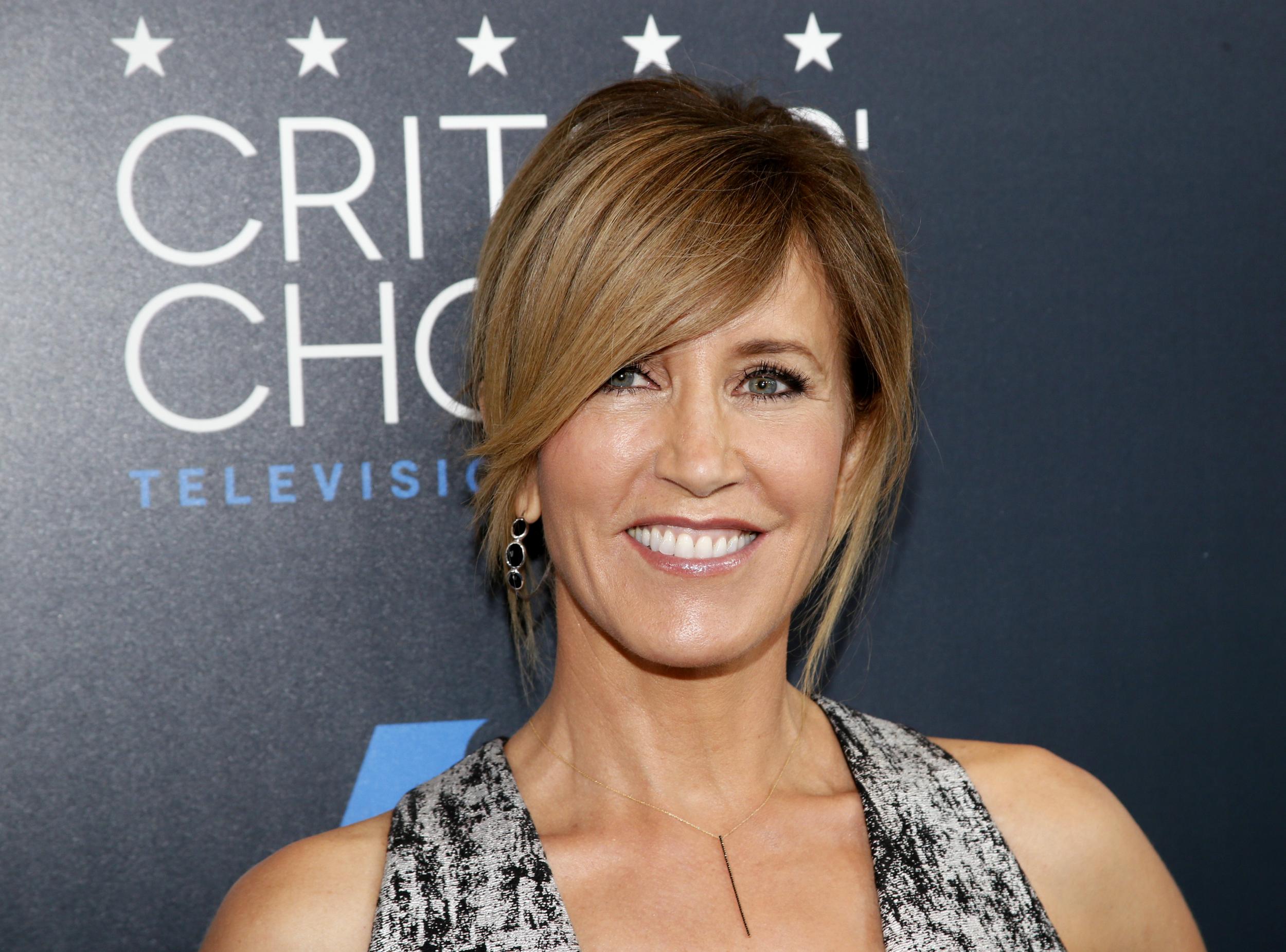

The memes came thick and fast this week as Huffman was declared 'iconic' by LGBT followers. But how do we square this supposed celebration with real-life misogyny?

This week, US federal prosecutors charged 50 people over a $25m scheme that allegedly helped wealthy Americans buy their children’s way into elite universities.

The stench of overt privilege, cheating and elitism certainly made the scandal worthy of front-page news coverage. But the alleged involvement of actresses Felicity Huffman and Lori Loughlin, who were among those charged, added the sprinkling of Hollywood glamour, setting the story further alight.

As the news spread, Huffman – who famously played Lynette Scavo in ABC’s Desperate Housewives – soon became the face of the story. Images of the actress were used to illustrate news reports and think-pieces, like the one you’re reading now.

The standard reaction to a scandal like this is universal condemnation — but, while there was a fair amount of disapproval, my Twitter timeline more closely reflected a mood of unexpected glee. Memes and Desperate Housewives GIFs began to flood social media.

Gay men like me seemed particularly entertained by the scandal. “Honestly I don’t care about Brexit, hook the Felicity Huffman college bribery scandal into my VEINS,” tweeted gay journalist Guy Pewsey. Evan Ross Katz, a gay fashion and culture writer, turned court sketches of Huffman and Loughlin into tote bag designs. A 28 February tweet sent by Huffman in which she described her husband as her “partner in crime” went viral. Quoting the now-deleted tweet, gay comedian Ryan Houlihan said: “SHE LEFT US ALL THE CLUES”. Ira Madison III, host of Crooked Media’s pop-culture podcast ‘Keep It', tweeted: “Felicity Huffman obviously should go to prison..... unless ABC wants to reboot Desperate Housewives, because in that case...”

The list of jokes goes on (and on) because, let’s face it, the tweets really do write themselves. But why did gay men in particular have such a jubilant reaction to what are extremely serious allegations? Why is Huffman being described as a “gay icon” for being accused of engaging in morally reprehensible and allegedly criminal behaviour?

Madison’s tweet, which referenced Huffman’s role on Desperate Housewives, provides the first clue. Quite simply, there’s something undeniably hilarious about life imitating art. In the fifth episode of season 1 of the ABC comedy-drama, which ran from 2004 to 2012, Huffman's character Lynette and her husband Tom "donate" thousands of dollars to get their twin sons into an elite private school. In a later season, Lynette discusses with fellow Wisteria Lane resident Gabrielle Solis how she’d fare in prison. The similarities are creepy.

A tweet by Daniel D'Addario, chief television critic at Variety, reveals a further layer to the gay infatuation with Huffman’s scandal. D'Addario tweeted a promo image for Georgia Rule, a 2007 teen flick starring Huffman alongside Lindsay Lohan and Jane Fonda – two actresses who’ve had their own brushes with the law. Accompanying the image were two mugshots – one of Fonda from 1970 and another of Lohan from 2013. Lohan has turned bad behaviour into an art from and, over the years, it has become an integral part of her public persona. Like Huffman and Fonda, she has a loyal gay fan base. D'Addario captions his trio of images: “We're about to complete the trifecta”, implying excitement that Huffman’s mugshot might soon join her co-stars’.

Many women who are considered “gay icons” earned this status through flouting conventions and even by breaking the law. Supermodel Naomi Campbell, who is universally considered a gay icon, famously wore couture gowns to community service for hitting her housekeeper with a mobile phone. Half of the current cast of Bravo reality show Real Housewives of New York City have mugshots.

Across the Atlantic, in the UK, British Member of Parliament Fiona Onasanya became the first politician to vote in parliament wearing an electronic ankle tag last week. She voted after being released from a custodial sentence she served for lying to police. The response from “gay Twitter” is best encapsulated in a viral tweet that said: “This woman is iconic. sorry I don’t make the rules”.

The “bad woman” fantasy isn’t confined to real-life news, either; in works of fiction, “bad women” remain firm gay favourites. Ocean’s 8 saw an all-female cast – including Cate Blanchett, Anne Hathaway, Rihanna and Sandra Bullock – star as heist robbers. LGBT+ writer Jill Gutowitz observed that the film “is inarguably a gay movie”, despite none of the characters being outwardly queer. Chicago, based on the Broadway musical, is another example. It saw Catherine Zeta-Jones and Renee Zellwegger play murderous jailbirds.

More recent examples of fictional “bad women” beloved by gay audiences include lawyer Annalise Keating in How to Get Away With Murder and the female leads of Orange is the New Black, Killing Eve and Oscar-winning film The Favourite. Interestingly, in these more recent examples, many of the “bad” female characters are queer themselves, further ingratiating them with gay audiences.

In music, pop stars with large gay followings frequently portray themselves as “bad”. The video for Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” sees the singer escape from jail with help from Beyoncé, who featured on the song. Similarly, Gwen Stefani’s video for “Sweet Escape” also sees her breaking out of prison. Beyoncé’s latest tour, alongside her husband Jay-Z, is called “On the Run”. Rihanna is known on social media as “badgalriri” and, in the opening line of her 2010 single S&M, she sings: “Feels so good being bad”.

In the book How to be Gay, queer historian David Halperin analyses the popular culture that gay men produce and consume. He observes that gay men are often “highly critical, if not contemptuous, of their own artists, writers and filmmakers”. Halperin concludes that, because gay men “don’t often like the representations of gay men that gay men produce”, they often fail to warm to gay characters and celebrities.

Halperin argues that most representations of gay men in pop culture pander to “acceptable” mainstream heterosexual norms, meaning that gay viewers end up looking elsewhere for characters to empathize with. He even cites Desperate Housewives as an example of how gay men can feel more represented by pop culture’s heterosexual women than its gay men.

Halperin draws a distintion between gay culture — where apolitical, conventional gay men are front-and-centre — and gay subculture — where women, drag queens and gender non-conforming people are amplified. Gay men search for a more subversive subculture in female narratives, while shunning a “sterilised” mainstream gay culture.

Consider what José Muñoz calls “disidentification”: the way in which LGBT+ people assign queerness to characters or stories that are not explicitly queer. Disidentification supposedly represents an early coping mechanism. As an example, Munoz suggests that when a gay man “identified” with Judy Garland, he was “writing his way into the mainstream culture in which his own story could never be told”.

In many ways, the Desperate Housewives cast represent accepted female norms, particularly physically. But they are also duplicitous and manipulative. They commit crimes, cheat, lie and certainly aren’t afraid to cause a scene. Many would see them as caricatures or parodies (the title of the series would certainly suggest so).

Promotional images for the third season of Desperate Housewives perfectly encapsulate the appeal. One image, taken face-on, shows the four central characters in silk gowns looking serene. Brie Van De Kamp, played by Marcia Cross, holds out a delicious, freshly baked pie. But the next image captures the view from behind. Each woman is concealing a weapon behind her back, including a cane, handcuffs, a knife and a pair of scissors. It’s spine-tinglingly camp.

Queer communications professor Noreen Giffney defines “queerness” as a “radical resistance of categorisation and norms”. Given this definition, it is easy to see why gay men night perceive more of a queerness in images of pristine housewives holding weapons than a conventional gay couple like Bob and Lee (Wisteria Lane’s token gay spouses, who are among the show’s most conventional, un-troublesome characters).

So-called double deviance is also useful for understanding the gay affinity for “bad” women. Double deviance describes the way in which women are judged more harshly for immoral behaviour by society, especially criminal behaviour, because they are assumed to be “deviant” in terms of breaking the law and “deviant” in terms of going against the expected norms of their gender. Women who kill their children are, for example, often handed down longer prison sentences and subject to more media scrutiny than fathers who do the same.

Growing up, many gay men will have heard homosexuality described as “deviant” and therefore associated their sexuality with feelings of shame. So is it any surprise that so many take enjoyment from the idea of a woman who is unashamedly deviant against the law, or deviant against the gendered expectations of women to be kind, submissive and well-behaved? Think Uma Thurman’s Kill Bill character: she’s gender-deviant and unapologetic to the point of being deadly.

So we can accept that a deviant woman is a freeing trope for a gay male viewer. But how do we square that with the fact that such ironic adulation can also be dehumanising, even misogynistic, when applied to real-life cases? Take as one memorable example the treatment of young actress Amanda Bynes. Or, perhaps, the mockery of Britney Spears’s personal life. Recently a gay fan was widely condemned for posing alongside Spears with a green umbrella, which she infamously used to hit a paparazzi car at the peak of her 2007 public breakdown. Gay men should be mindful that, while fictional “bad women” can be admired, real women are not playthings who exist for our entertainment. We should not attempt to control their personal plotlines.

Ultimately, the “bad woman” archetype represents a de-closeting narrative. These female characters or reality stars onto which gay men can project provide comfort, capturing a fearlessness they respect or wish they’d had at points in their lives when they were perhaps mocked for exhibiting traditionally feminine traits themselves.

Just as gay men represent a masculinity divorced from heterosexuality, “bad” women represent a femininity than stands apart from conventional, “acceptable” femininity. Scandals like Huffman’s blur the line between reality and fantasy, but also subvert restrictive, gendered expectations. You might ask: What’s more queer that? And I’d say: Nothing at all. Laugh and love all you want — so long as you’re mindful of the the ethics of being an audience.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments