Football, my father and me: how the pitch became the emotional middle ground we desperately needed

Thanks to the sorry state of masculinity, the sport provided one of the few spaces where we could connect. Like so many others, when words failed us both, the game bridged the gulf between us

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

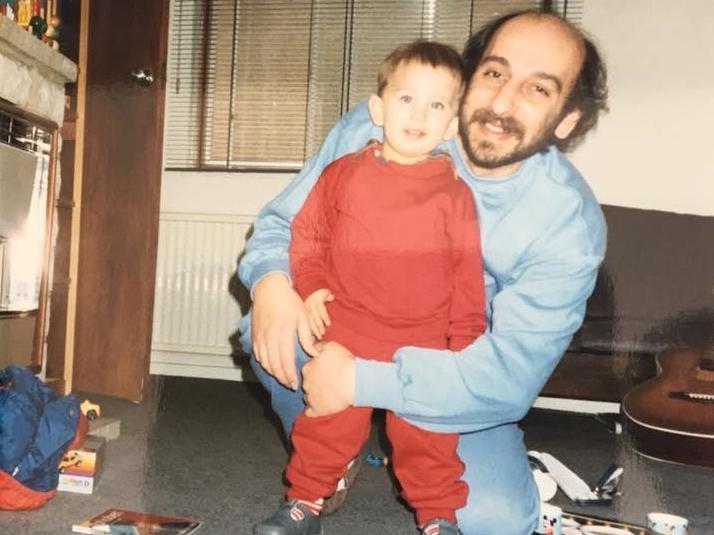

Your support makes all the difference.Before dementia began stealing my dad’s memories, he’d tell tall tales about me: swinging my left foot at a ball almost as soon as I could stand, or how toe-punts with him on the unkempt grass of our garden developed into kick-arounds in the park with friends. From there, I progressed to joining a team, utterly convinced by my own precocious talent; I was destined to be the next Kung-Fu-kicking King Cantona.

My dad spent countless weekend mornings shuttling me across north London to my games, braving gale-force winds and sheets of the best British rain to patrol the touchline like a sentry. His robust mixture of criticism and praise rang out in my ears as I did my best for the team, but more importantly, my best to impress him by joining the swarm of other boys and flying around the pitch like an angry wasp.

The old man wasn’t unique in his presence pitch side. Our matches were amass with feverishly over-invested dads and a sprinkling of mums doing their utmost to drive us to victory by shouting “PLAY THE EASY BALL,” delivering incomprehensible tactical instructions and swearing at the ref.

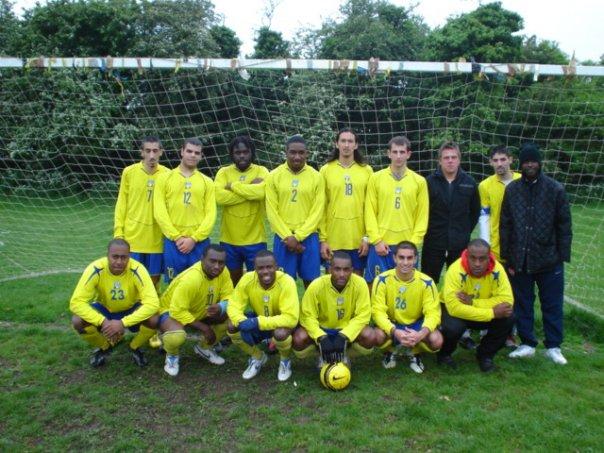

By the time I was 16, I’d realised that scouts for professional clubs didn’t recognise greatness when it stared them in the face, so started playing senior football in the local Sunday league with a bunch of like-minded young men. I was trapped in that purgatory between childhood and adulthood, making the risky choices working class boys sometimes make, very much performing the role of a bad man. The last thing I wanted was my dad turning up to my games.

But there he was, every Sunday morning without fail. Even if I’d told him not to bother coming. Even when I'd been out all night on the roads, stoned out of my nut and not sent a text to tell him where we were playing, he was there. He’d drive around to all the spots where games kicked off and get out of the car when he spotted us in our colours, going through the motions of a shambolic warm up.

Now my old man was conspicuously alone in his support. Gone were the other parents, their Klopp-like gesticulating and expletive-filled rants. It was just him. I resented him being there at first, but quickly accepted that the boys really valued his presence. His positive energy was contagious, and if things were going south, he offered great motivational speeches at half-time. He gave us self-belief, when we perhaps didn’t have much, in both sport and in life.

My dad’s guidance went further than the football pitch. When our striker chinned the opposition’s goalkeeper, a particularly competitive game threatened to descend into a mass brawl, which can have disastrous consequences in my ends. My dad stepped in and put a protective arm around him. He spent a few minutes talking to our striker, who then apologised to the man he’d punched. Something that could’ve got so much worse was suddenly better. I never got to see my dad in his job teaching maths and P.E in secondary school, but I began to grasp what made him so respected amongst the teenagers he worked with.

After my games, we’d sit down on the sofa to watch Super Sunday and unpick what went down on the pitch that morning. I was always taken aback by how much my old man had to say about my team-mates. At first it stung my pride a little bit. “Why weren’t you paying more attention to me?” Then I understood; he wasn’t just there to watch his son play, he was there for all of us. We were all wayward young men, to varying degrees. We needed him and he knew that.

Whenever I check in with my old team-mates online, or if we bump into each other on the street, the first thing they ask me is how my dad’s doing. Because of his illness, my dad’s recollections of that period in our lives is hazy at best, and sometimes non-existent. But if I ask the right questions, he can still recall specific moments, like Neil running the length of the pitch before smashing one in off the bar, or AJ scoring a last-minute penalty in a cup semi-final against our arch rivals, and the mad bundle that followed. “They were all my sons,” he often says of the boys I had the honour of playing with.

Like too many of us, football has been a precious bridge between me and my old man. It provided one of the few spaces where we could connect emotionally. I think this says more about the sorry state of masculinity than it does about our relationship. I guess him being there, week after week, season after season, was his way of telling me he loves me. And when I read this piece to him today, after the last line, I’m going to tell him I love him too.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments