A-level and GCSE grades should be determined by more than stressful end-of-course exams

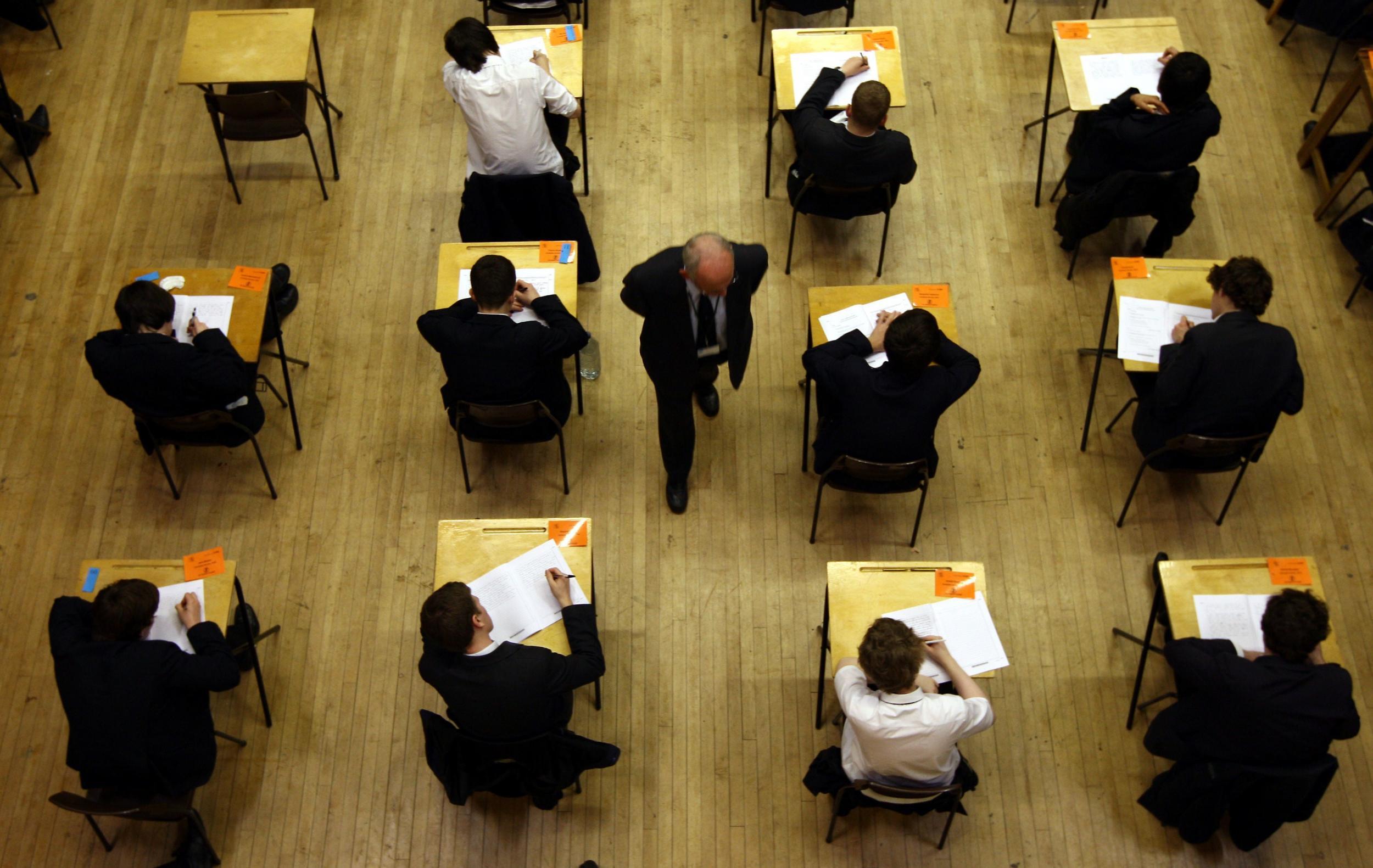

When mental health is at the forefront of policy, what is the impact of so-called ‘terminal exams’ on young people who do not respond well to the pressure?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Teacher Assessed Grades (TAGs) are in and as teachers turn their attention to “normal’’ end of term activities, like sports days and reports, we can all share in the collective sigh of relief.

However, will the results be an honest reflection of pupils’ achievements? And is it fair that children this year may have been more favourably scored than those in previous years – or future years for that matter?

No doubt these questions will be raked over in the weeks ahead but the reality is, this year’s arrangements are the best way to ensure our 16 and 18-year-olds are not robbed of their life chances, and get their ticket to move on to the next stage in their lives. I hope we can all remember this.

Come results day in August, we need to be celebrating teachers’ hard work in helping our children get through it all, rather than focussing on cries of bias or foul play, unprofessionalism and grade-inflation.

Such criticisms will give the secretary of state the ammunition he needs to return to exams next year – arguing they are, in his words, “the best and fairest way for young people to show what they know and can do.” And indeed, a recent survey shows teachers reaching out for the familiarity of exams – an understandable reaction after two years of turmoil.

My frustration is that this will obscure a more important debate we need to have about assessment. How fair is it that an entire two years of study comes down to performance in a two-hour exam? Like the athlete whose success, following years of graft in training, rests solely on one performance, in one moment, at the Olympic finals. But GCSEs and A-levels are not Olympic events, and results should not be wholly based on a one-off performance.

To my teenage daughter and her friends, our examination system doesn’t best test knowledge and skill, but instead tests their ability to regurgitate a certain bit of the syllabus, according to a strict marking criteria, under time (and emotional) pressure. Good for children who can store lots of facts and work under extreme pressure, but not a good means of assessing a child’s true ability or depth of knowledge in a subject.

And children know the stakes are high. When mental health is at the forefront of policy, what is the impact of so-called “terminal exams” on young people who do not respond well to the pressure? I need look no further than my own experience as a youngster to exemplify this: coursework and essays rated me an A grade student, exams were at best a B. Why? I rarely slept or could eat anything before an exam.

Now, talking to thousands of youngsters and head teachers from all over the world, exam worry is one of the biggest causes of serious and debilitating anxiety in teenagers.

Add to this, as we have learnt to our peril, the traumatic shock to the system when exams can’t go ahead. With so much uncertainty as to how new Covid variants will affect the world, it is a brave government that puts all its eggs in the exams basket.

So to my mind, the most accurate, fair and rigorous way of assessing a child’s learning, ability and application is continuous testing over the duration of the course. That’s not to say that an end-of-course assessment doesn’t have its place – it certainly does. But it should not count for the entire grade.

It should count for, at most, 25 per cent of the final grade, with the remainder calculated through controlled assessments at the end of each module. It wasn’t long ago that this was the case, but continuous assessments disappeared in many subjects following Michael Gove’s reforms as education secretary.

Now, as we move (we hope!) through the pandemic, there is only one sensible option to safeguard the authenticity of grades, and that is to re-introduce continuous and controlled assessments. For GCSEs and A-levels, this will mean far more formal assessments led and marked by teachers, and a more rigorous moderation process at local and national level than currently in existence – not developed in a panic during a pandemic.

There is certainly work to be done to ensure teachers have the tools, time and training they need to accurately set and formally assess at GCSE and A-level. Equally so for Ofqual and perhaps Ofsted, who must ensure standardisation and integrity of “school-led assessments”.

To enact such a change of policy will be a significant shift for the Department for Education and sector as a whole. But allowing children to truly demonstrate what they know in environments that allow them to do so must be the right way forward.

Professor Geraint Jones is Executive Director and Associate Pro-Vice-Chancellor at The National School of Education & Teaching, Coventry University

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments