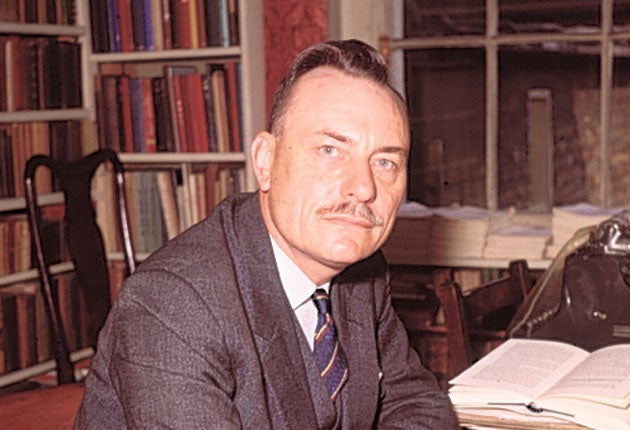

Enoch Powell's 'Rivers of Blood' speech marked him out as the prototype Trump

Fifty years on, were any of Enoch Powell’s predictions correct, and what does that tell us about what the UK will look like in 50 years’ time?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fifty years ago this week, a speech that was to change British politics forever was delivered: the “rivers of blood” speech, by Enoch Powell. We are still living with its consequences.

Though he never said “rivers of blood”, he did use a great deal of offensive, albeit memorable, language. Powell did talk about “excreta” being put through letter box of a frail old lady, allegedly the last white woman in her street in Wolverhampton (which Powell represented in the Commons).

He did mention “charming, wide-grinning piccaninnies” who knew only one word of English – “racialist”. (Disappointing, by the way, but telling, that Boris Johnson alluded to “piccaninnies” with “watermelon smiles” years later).

Powell did quote from Virgil: “Like the Roman, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood.” He did declare: “Those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first make mad. We must be mad, literally mad, as a nation to be permitting the annual inflow of some 50,000 dependants, who are for the most part the material of the future growth of the immigrant-descended population. It is like watching a nation busily engaged in heaping up its own funeral pyre.”

And he certainly did relay the view of a constituent who told him that “the black man will have the whip hand over the white man”.

He did, as he intended, stir things up.

But, to pose the question that has been asked on and off ever since: were any of Enoch’s predictions correct?

In one narrow sense, he was right. The increase in the “immigrant” population – which became interchangeable in his thinking with what we would now call Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic (BAME) – was much as Powell predicted it would be, allowing for his fuzzy/misleading definitions.

According to the ONS, in 2011 the “usual resident” population of England and Wales that could be classified as non-white was 14 per cent – rather higher than Powell’s extrapolations. It seems pointless to quibble about that.

It’s crucial, though, to nail the insidious idea that Powell propagated, sometimes explicitly, more often by sneaky logical ellipses: that you cannot be black and British (which is how he underpinned his demographic forecasts).

Towards the end of his life, he was asked again about this for the BBC by Michael Cockerell. Asked if a black person could be British, Powell replied: “It is not impossible. It is difficult.”

The very concept of “black British”, of black and Asian people making the kind of patriotic contribution to British society at every level that we take for granted, was anathema to Powell. “Race is the basis of identity,” he thought. In that, Enoch was demonstrably wrong.

The “whip hand”? Racial discrimination working against white people?

Hardly. By the 1980s, the degree of social and economic discrimination against Britain’s black community had become so grave that it provoked riots. Even Margaret Thatcher, as premier, and long an admirer of Powell, had to admit that race relations had gone badly, badly wrong.

Sadiq Khan, Diane Abbott, Mo Farah, Jessica Ennis-Hill, Benjamin Zephaniah, George Alighai, Cyrille Regis, Stormzy, Zadie Smith, Meghan Markle …The whip hand? It is, really, preposterous.

It wasn’t Powell who said it, originally. It was said to him by a constituent, “a middle-aged, quite ordinary working man employed in one of our nationalised industries”. So depressed was this chap that he wanted his children to emigrate.

Powell’s case was that he had no choice but to voice such concerns. Yet it wasn’t true: he could have argued back, set the man’s mind at rest, argued in favour of a multicultural society. Except that Powell didn’t believe in any such thing.

He was perfectly entitled not to, but, it would have been better if he had checked the stories and eased the paranoia. He turned at that moment from statesman to mere cornershop gossip.

And what of the river foaming with blood? In Powell’s view, the UK was headed for the sort of communal bloodshed that characterised India after partition and the evacuation of the British in 1947-48, or the continuing racial agonies of the US, which he alluded to in his speech. (Martin Luther King had been assassinated 16 days before Powell’s address).

He believed that legislation to outlaw race discrimination – a Bill was then being debated in Parliament, which gave Powell the “peg” for his speech – would create further tensions among the “indigenous” population.

The evidence, though, is that a succession of laws led the way in changing cultural attitudes to the extent that racism today is socially unacceptable. Powell, by contrast, thought there’d be a civil war by now: a race war, in effect.

In a 1977 TV interview he doubled down on his lurid predictions: “The prospect is that politicians of all parties will say, well, Enoch was right, we don’t say that in public, but we know it in private…”

“So let it go on until one-third of central London, one-third of Birmingham, Wolverhampton are coloured, until the civil war comes. Let it go on. We won’t be blamed. We’ll either have gone or slip out from under somehow.” Well, there is no civil war. Enoch, once again, was wrong.

Powell – in a very 21st century populist, Trump-esque, way – created the impression that there is some conspiracy by the establishment politicians to perpetrate an act of “betrayal”.

He, on the other hand, so he claimed, merely gave voice to millions we’d now call “left behind”, often traditional Labour voters. He spoke for them literally, with his authentic Brummie accent, in contrast to the usual Tory plummy vowels or elocuted speech.

Powell was quite dishonest. No one, despite an army of reporters descending on the Black Country, ever found the legendary little old lady, and no one ever met the working-class Wulfrunian who despaired of Britain.

The letter Powell received from Northumberland, which (second-hand) recounted the story about the pensioner, was oddly never produced. Half a century on, it all sounds like “fake news”.

Enoch was right, on other hand, about the impact his speech would make. When he was planning it he had apparently told Clem Jones, the editor of the Wolverhampton Express & Star, that he expected his speech to fire into the sky “like a rocket”, and that, unlike a rocket, it would not fall to earth but stay up in the firmament.

Powell made sure the TV cameras were there, and that the press knew what was about to happen. The Conservative Party press office was kept out of it, for Powell knew it would infuriate his colleagues in the shadow cabinet. It did, and he got the sack.

Powell gambled that the race issue would propel him into the Tory leadership and thence No 10. Yet all he succeeded in doing was to generate a huge swing away from Labour and towards the Conservatives in the key West Midlands marginals, at the 1970 election. He made Ted Heath, the leader who he so disliked, prime minister, and that, as Powell put it, “sealed my exile”.

So Enoch was wrong to think that race was his shortcut to power.

Still, you could say Powell has had a curious vindication since his death in 1998. For if Powell dedicated his life to the immigration issue, his other great passion was getting Britain out of the European Union: thus, Brexit might be judged the triumph of Powellism.

There is a reason why Nigel Farage has been called a “poundshop Powell”. Perhaps we are piling up our own funeral pyre – though not the one Enoch Powell had in mind.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments