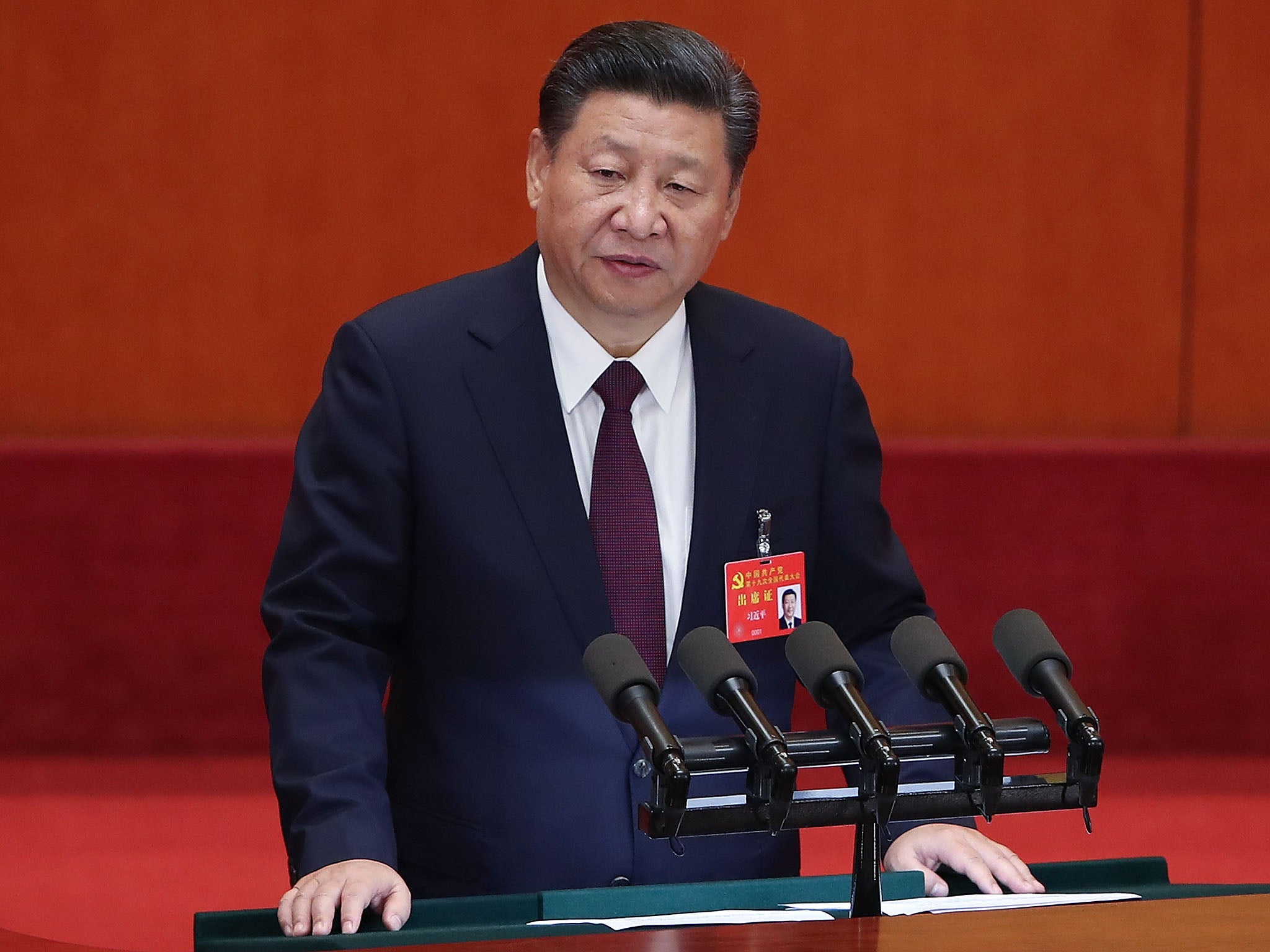

Xi Jinping's ideology has little substance, meaning the world must guess how to assess it

China will be fortunate if it manages to escape a crash that would mirror the West’s financial crisis of 2008, since at least some of the same factors are already at work

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Pity the generations of Chinese schoolchildren who will now find themselves grappling Xi Jinping Thought as a compulsory subject on the curriculum. Having ensconced himself in the very text of the Chinese constitution – an honour previously bestowed only on Chairman Mao and Deng Xiaoping, and even then posthumously – Mr Xi has, in effect, made himself autocrat of all China, maybe for life. As a result his beliefs now form part of a national religion, one that all Chinese pupils and students will be required thoroughly to understand and to regurgitate on command.

As it happens, the essence of Xi Jinping thought is not difficult to grasp. First, there is the absolute and unchallenged authority of the Chinese Communist Party over all aspects of life in the country. This has obviously been the case since the end of the civil war and the triumph of the Maoists in 1949, but it today has a more strongly oppressive favour.

Second is the projection of Chinese power intentionally, its military and diplomatic role catching up with its economic and industrial prowess. Again, these are hardly new developments, at least since Deng set the country on the road to economic liberalisation; but the insistence on “socialism with Chinese characteristics” indicates a reluctance to cleave towards Western values and assumptions. “Convergence” between the Chinese way of doing things and the West is not part of Xi Thought.

Beyond that, however, defining Xi Thought is a more like nailing jelly to a wall. This is because it comprises whatever it is that Xi decides to do at any given moment; it has less intellectual consistency than any of the other elements of Chinese state ideology – Marixist-Lenism, Mao Zedong Thought and Deng Xiaoping Theory. It is code for personal rule, a near dictatorship with a strong man at the top. That is what will make getting an A-grade in the subject challenging – and which also makes life difficult for the rest of the world as it tries to assess where Xi wants to take his country.

Mighty and more assertive as the Middle Kingdom has grown, it plainly faces serious structural challenges. Such are their seriousness that they may even threaten Xi’s position, if the worst prognostications come true.

For some time, for example, observers have wondered how long the Chinese financial system can survive in its precarious state. China has too many banks that have lent too much to the wrong kinds of people for the wrong kinds of projects. “Chinese characteristics” here place job creation, prestige projects and a near-obsession with infrastructure well ahead of the kind of market signals that capitalist economies usually rely on for an efficient distribution of scarce resources. So an awful lot of money gets wasted. As a result, many loans have little if any chance of being paid back to the banks, as they were used for economically useless ends, with no profits and no returns available.

China’s financial system is still guided, to use a polite expression, by the authorities in Beijing, and is notoriously opaque, but the stresses are there even so. China will be fortunate if it manages to escape a crash that would mirror the West’s financial crisis of 2008, since at least some of the same factors are already at work – principally overstretched banks with fictional assets on their balance sheet. Xi's reputation would not be enhanced if he had to preside over the kind of recession seen in Europe and America a decade ago.

There is also a question of just how assertive China can become without endangering its own security. In the South China Sea, China’s neighbours are concerned about constant territorial expansion and claims, often centring on obscure islands (some manmade) with disputed sovereignty.

China’s quest for its territorial integrity, independence and external security stem form a deeply felt resentment at the humiliations visited on the Chinese people by foreign imperialist powers before 1949. Yet there is so much overcompensation for that going on now that it risks alienating and provoking countries from Japan to the Philippines who have no other quarrels with China. China’s naval and military buildup risks making it less secure, not more. The recent elections in Japan signal a change to the country’s pacifist constitution that Beijing should not be so surprised about, given China’s own new nationalism and tolerance of North Korea’s antics.

Xi Jinping has a claim now to be more powerful in the world than Donald Trump, but that does not mean that China can or should try to push America around, tempting as that might be. China can and should do more to restrain North Korea, or at least try to, given Kim Jong-un's stubborn habits, and should not treat every request from America for diplomatic support or reform of their unequal trading relationship as an attempt to subordinate China. Sino-American diplomacy has drifted into being perceived as a zero-sum game, when in reality there would be much mutual gain if both sides returned to the kind of warmer relations that had developed in the 1990s and 2000s.

Mr Xi is nervous about making the mistakes that Russia made in the shambolic years after the end of the Soviet Union, when the USSR broke up and it was left impoverished – something since remedied, or so the Chinese believe, by the personal rule of Vladimir Putin, a style Xi looks keen to imitate. That memory of what happened to the senior of the two old communist superpowers, as well as a longer memory of historical slights, also explains why Mr Xi and the Chinese state stress the unity of the enaction and the role of the Communist Party so forcibly.

There even seems, more positively, a genuine urge to rid the country of its petty (and not so petty) culture of corruption and to clean up the poisoned environment. It is an open question, though, as to whether the renewed pressure on dissidents, notably in Hong Kong, on minorities such as the Tibetans and Uyghurs, and on free speech will, in the end, strengthen the party’s vanguard role in leading China to its place in the sun. Maybe Xi Jinping will in due course offer China and the world his thoughts on that.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments