Increased financial support is needed to encourage people to follow the rules

Editorial: The only way of slowing coronavirus transmission is by suppressing it across wide areas, regardless of a tier system, so a Christmas amnesty is hugely dangerous

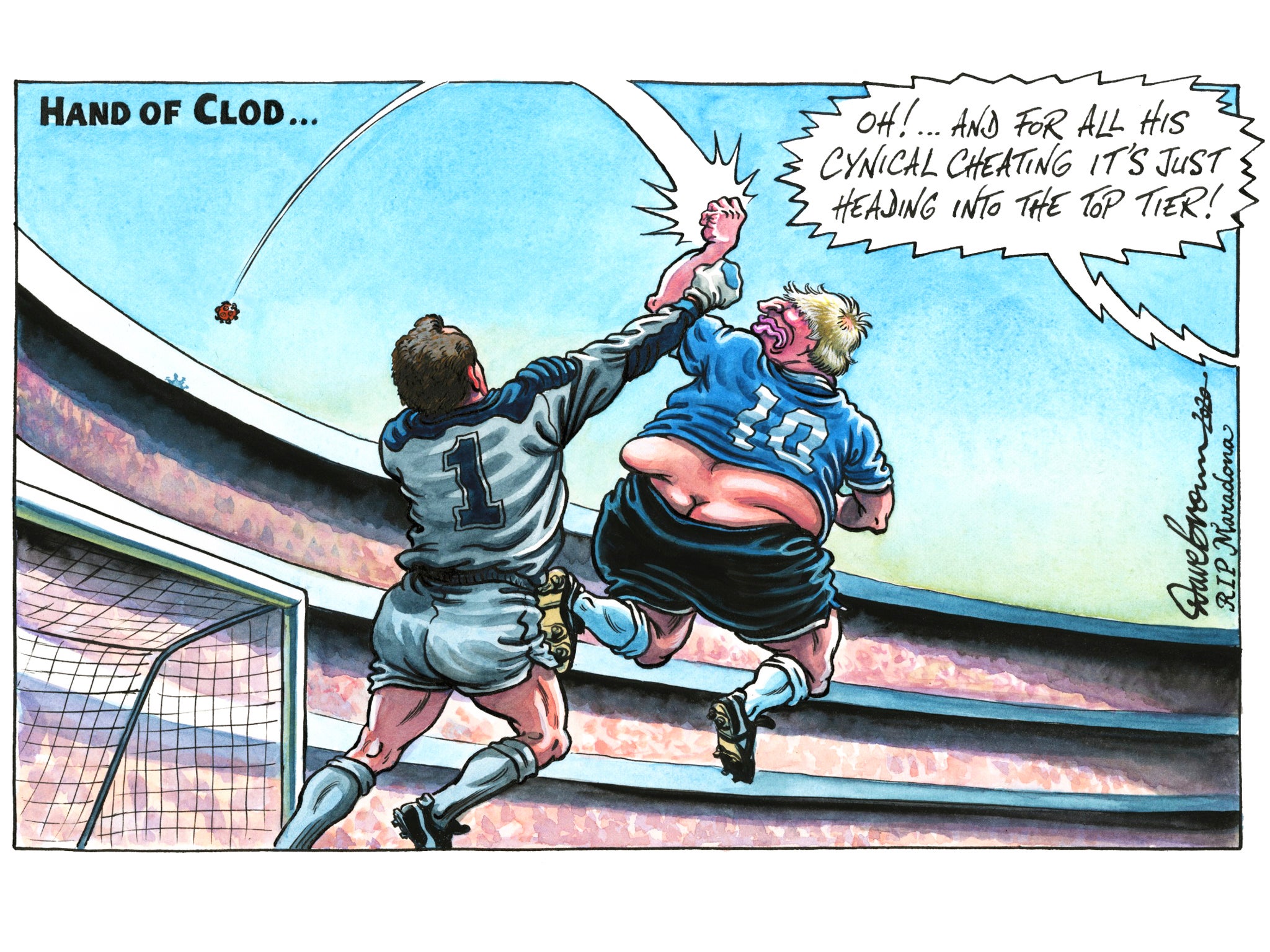

It was inevitable that for most places in England the release from national lockdown would simply mean a transition to a form of “tiered” local lockdown, and little practical difference. As Boris Johnson said at his latest public appearance, there are hard months ahead. Apart from Cornwall, the Isles of Scilly and the Isle of Wight, which return to the halcyon pre-tier freedom of the “rule of six”, every part of England will be in the “high” or “very high” tiers, as will, in equivalent form, most of Scotland and Northern Ireland. Wales, after its earlier “firebreak”, is relatively relaxed, for now.

This was entirely predictable because the recent second national lockdown, just like the first, was late in arriving and probably concluded too soon, at least in epidemiological terms. Case rates in many parts of the country remain high, threatening the capacity of the NHS. The lockdown has no doubt helped the situation everywhere, by reducing infection rates compared to doing nothing and carrying on under the original tiers. However, in absolute terms, some counties or towns have seen higher cases, while others are seeing rising rates. These are the ones that entered lockdown in tier 1, but emerged going into tier 2 or tier 3.

This, in turn, has led to a chorus of protest from mostly Conservative MPs pleading for their local areas. Some, such as those in Kent, wish to partition their counties. It is as if local pride has been offended by the movement of coronavirus around the country, the implication being that certain regions are the victims of other lawless, careless, or unclean places nearby. The spirit of national solidarity has been rarely glimpsed in recent days.

The fact is that this is a pandemic, and there is no place on Earth, with the possible exception of the Antarctic, that is free of it. The only way of slowing transmission is by suppressing it across wide areas, with test and trace dealing with small outbreaks. Even a vaccine will not eradicate it for many years, if ever. It is not practical to quarantine half an English county or a market town from the rest of humanity and declare them plague-free; they cannot be sealed off. It only takes a few superspreaders to travel a few miles to push infection rates up. It can grow as asymptomatically and exponentially as easily in Teignbridge as in Manchester.

Only in the most extreme circumstances, such as the Scillies, is a radical relaxation even remotely practical. It might be said that no man is an island, so far as Covid is concerned. Alas, too many Tory MPs seem to think their fiefdoms have become immune to the disease through a superior sense of civic duty. They will rebel against the rules, if only to signal to their constituents that they are “on their side”. They know that the Covid tiers regime will survive, again, thanks to Labour MPs.

That is what makes the Christmas amnesty so dangerous. It will inevitably mean more people will be infected, by their own kith and kin, and some of them will find themselves in hospital, and some of them will be left with life-changing long Covid or they will die. The best that can be said for the UK-wide seasonal easement is that it deals with the reality that much of the population would ignore the lockdown around Christmas. Allowing three families to mix for five days might at least encourage some moderation. Even so, some families will inadvertently “kill granny”, as the macabre saying goes.

It would be encouraging if the government was also offering financial support to people and businesses to encourage them to do the right thing. It would be still more heartening to see some evidence that the time and earnings sacrificed in national and local lockdowns had bought some time for a functioning test and trace system to finally arrive. As usual, it has not. And as usual, no one will accept responsibility for that failure, the root cause of the damage to public health and the national economy.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments