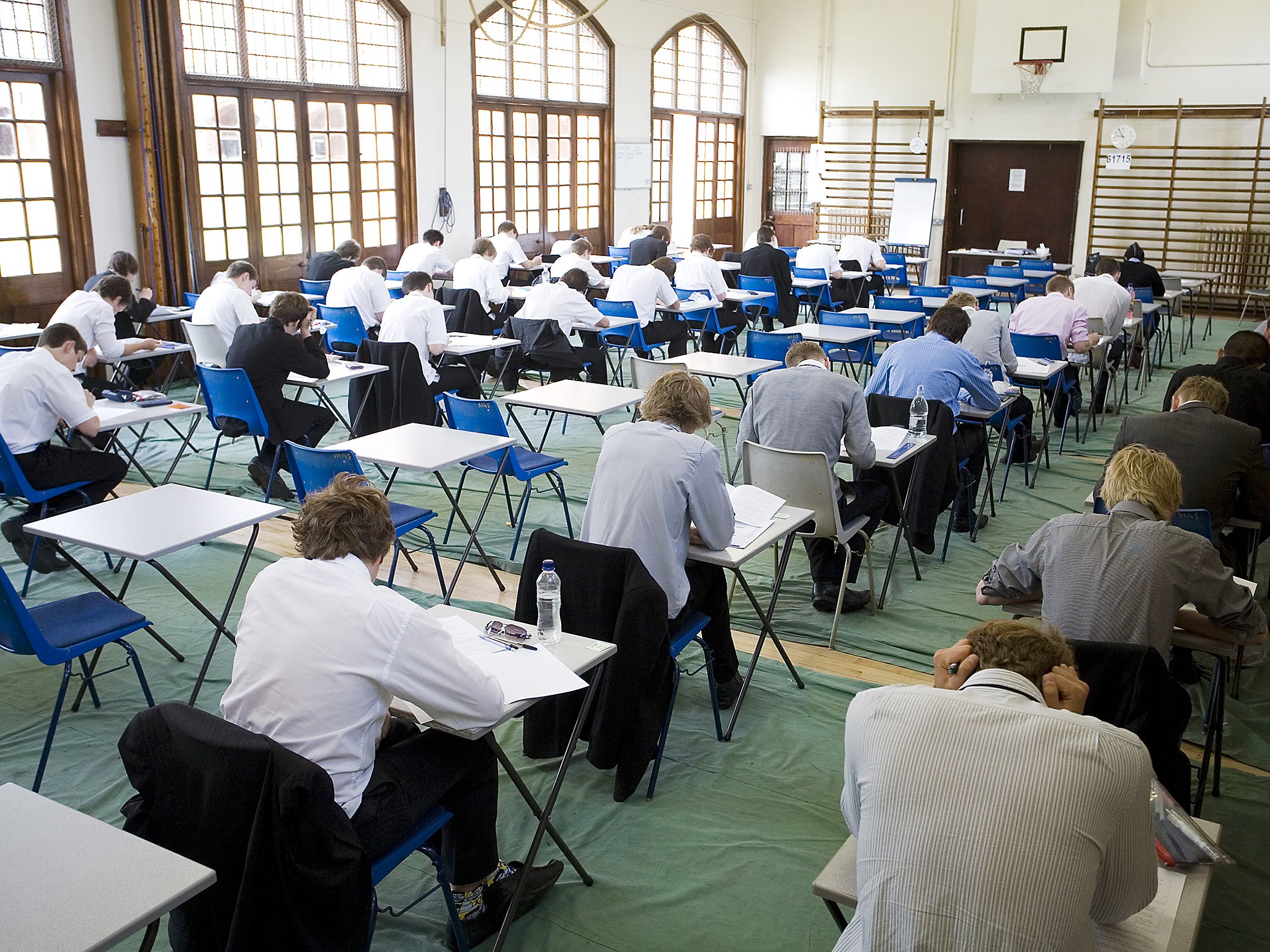

We need education reform – the grammar-comprehensive school advantage gap has never been so wide

Experiments in new types of schools and the expansion of the higher and further education sectors may help ameliorate matters, but social mobility is on a fast decline

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The latest report from the Sutton Trust, a charity that devotes itself to the crucially important cause of social mobility, demonstrates that educational inequalities extend far beyond the usual division between the state and private sector – though that remains the single most glaring of the many sources of inequality of opportunity.

Within state secondary schools too, there are a wide variety of outcomes – with the majority of children in the majority of schools suffering some detriment to future careers, earnings and status in society.

Thus, selective state schools – the grammar schools and their successors – enjoy success rates for applications to Oxford and Cambridge colleges that are far higher than those seen in general further education colleges, sixth form colleges and comprehensives.

There are also slightly perverse – though in their way encouraging – outcomes within the state sector, especially with the arrival of academies and free schools. For example, sponsored academies are frequently found in deprived urban areas where they have replaced “failing” conventional comprehensives. On the other hand, according to the charity, many converter academies were previously already high performing schools, with less disadvantaged intakes.

There are also clear, and indefensible, geographical differences in access to the better universities – Oxbridge and the other Russell group institutions. These are not confined to the inner cities or urban areas.

The list of underrepresented local authorities, according to the Sutton Trust, includes Southampton, Thurrock, Knowsley, Rochdale and Salford; but also Lincolnshire, North Lincolnshire and Rutland.

Overall, in its most eye-catching statistic, the trust finds that the eight best state schools and colleges sent as many pupils to Oxford or Cambridge over three years as three quarters (2,900) of all schools and colleges.

While the statistics, across a fast changing educational landscape, are complex and sometimes hard to interpret, the remedies suggested by the Sutton Trust are more obviously clear. Almost a quarter of students in independent schools in the top fifth of all schools for exam results applied to Oxbridge, but only 11 per cent of students in comprehensives in the same high achieving group of schools did so.

Of those who applied to Oxbridge from schools in the top fifth, 35 per cent were successful from independent schools, but only 28 per cent of those applying from comprehensives were accepted.

So results aren’t everything and, by corollary, even if state schools exam performances rose to the levels of the private sector, there would still be a disparity in the numbers of northern ex-comprehensive undergraduates turning up at Peterhouse or Christ Church.

Noting that pupils from state schools with identical A-level scores gain fewer places at the top universities than their counterparts at the top state schools and public schools, the trust recommends that the kind of extra-curricular and “rounding” experiences that are found routinely in the better schools should be developed in underperforming schools.

Thus, at St Paul’s, a public school, students are offered advisers at age 11 to guide their choices at GCSE and A level, with an eye on future university options. And while ski trips or expeditions to the Brazilian rainforest are expensive for just-about-managing parents or local authorities, setting up debating societies and coaching personal statements by applicants are not going to bust any school’s budget. They have to start somewhere.

Most puzzling of all, though, is the geographic bias by Oxford and Cambridge colleges, specifically, towards their “catchment area” in the south of England, even extending to an overrepresentation from the cities of Oxford and Cambridge respectively.

It is also fair to point out that, now as ever, some of the colleges of the ancient universities make more of an effort to reach out to the state sector, to develop relationships with teachers in deprived areas, offer open days and take calculated risks on teenagers with lower grades. Other colleges are stuffier and, frankly, prefer to simply rely on the same old feeder public schools that they have for centuries.

Either way, “access to advantage” as the Sutton Trust terms it, is as uneven as ever, with much evidence that social mobility has declined in recent decades. Innovations such as Sure Start, the pupil premium (a coalition government policy adopted from the Liberal Democrats’ manifesto), experiments in new types of schools and the expansion of the higher and further education sectors may help ameliorate matters. But given the landscape of education now, it would be simply naïve to expect much more equality of opportunity for this generation of schoolchildren.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments