Rishi Sunak has placed politics before principle – and demeaned himself

Editorial: The most expedient thing for the PM to do was to let Suella Braverman off with a mild public reprimand. She will cause less trouble this way. But he looks weak as a result

If the past few days have proved anything, it is that the Sunak administration is finding it exceptionally difficult to live up to the pledge that the prime minister famously made on the steps of Downing Street on his first day in office: “This government will have integrity, professionalism and accountability at every level.” Suella Braverman is certainly not the first name that springs forth when those noble sentiments are called to mind.

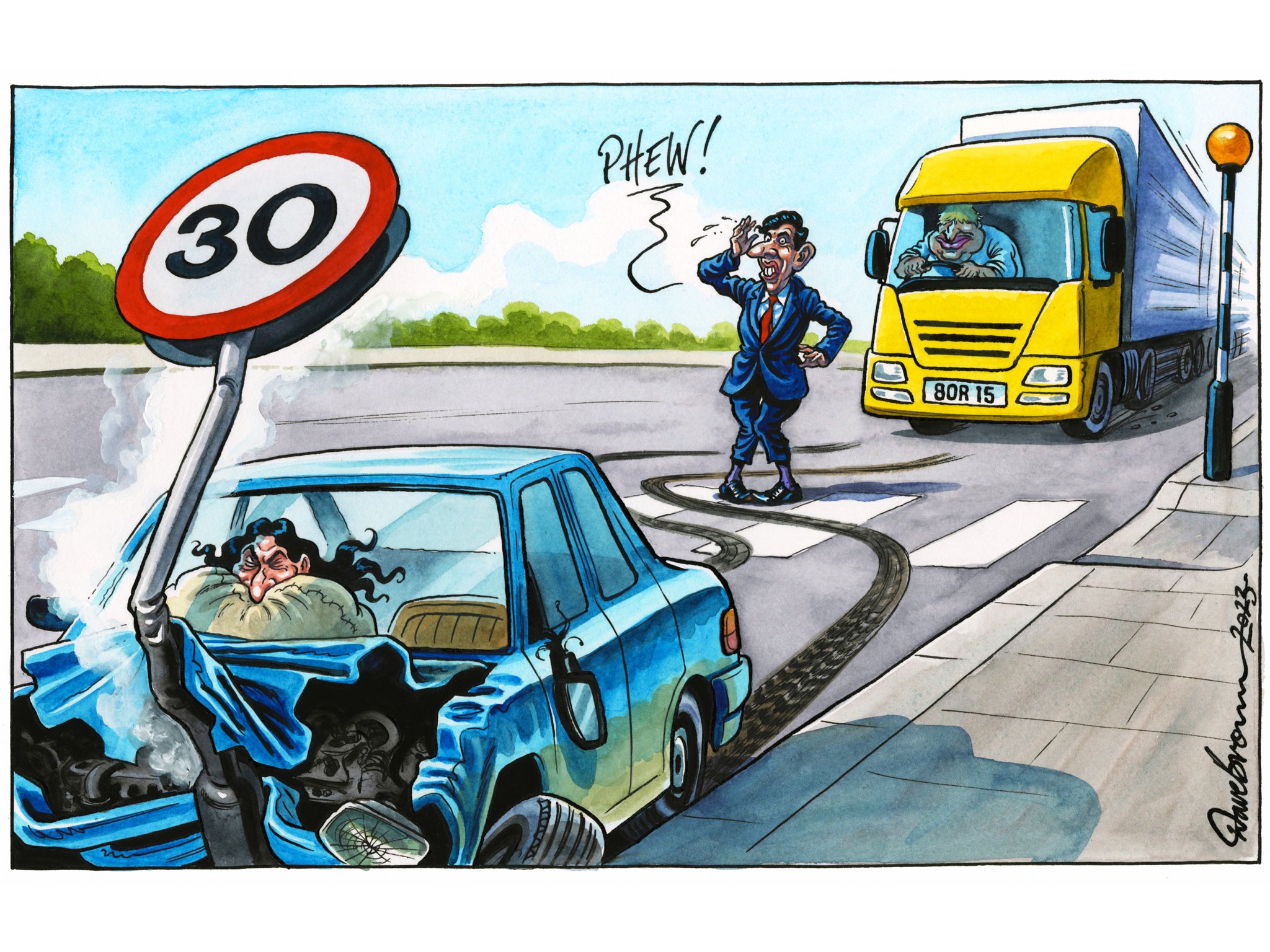

All too clearly, Mr Sunak is having to live with the continuing baleful legacy of Boris Johnson, who is now crying “conspiracy” over yet more apparent breaches of lockdown rules, this time at Chequers. Such reverberations from his predecessor’s reign of chaos are obviously not Mr Sunak’s fault, though they continue to grievously damage his (and his party’s) reputation. Disappointingly, though, and despite his work ethic and an improving economy, it has to be said that sometimes Mr Sunak is the author of his own misfortunes.

Nowhere has this been more clear than in his uncertain and hesitant approach to jettisoning failing colleagues, and in particular the home secretary Suella Braverman. Having dithered and delayed about asking for the resignations of Nadhim Zahawi and Dominic Raab, he has now ducked dealing with Ms Braverman entirely. She should never have been appointed in the first place, having had to resign over breaking the ministerial rules during the brief Liz Truss government. It seems Braverman’s reappointment to high office, to which she’s completely unsuited, was the price paid by Mr Sunak for her support in the autumn leadership election. That was unfortunate.

The prime minister’s decision not to ask his independent ethics adviser, Sir Laurie Magnus, to look into whether Ms Braverman broke the ministerial code by seeking a one-to-one speed awareness course is especially curious, but can be explained by the raw politics of the situation.

In their exchange of letters, there actually seems to be an acknowledgement that Ms Braverman did break the ministerial code, which requires that it is “the personal responsibility of each minister to decide whether – and what – action is needed to avoid a conflict or the perception of a conflict, taking account of advice received from their permanent secretary and the independent adviser on ministers’ interests”. It does appear that Ms Braverman did none of those things.

Moreover, in his letter to her, Mr Sunak states: “As you have recognised, a better course of action could have been taken to avoid giving rise to the perception of impropriety.” So a perception of impropriety did arise because she failed to prevent it through her actions; and therefore the code was in fact breached. Yet there is no sanction because the Mr Sunak judges that Ms Braverman has “provided a thorough account, apologised and expressed regret.” Not only has Ms Braverman got off lightly for breaking the Highway Code, but even more lightly for breaching the Ministerial Code.

The prime minister in his letter and remarks to the Commons also made no reference at all to the serious allegation that she’d instructed a special adviser to mislead the press about whether she’d received a fixed penalty notice for speeding; nor to The Independent’s revelations about her links to members of the Rwandan government, which is to receive some £140m from the British taxpayer to run the Rwanda refugee deportation scheme.

So the prime minister and his home secretary should be under no delusion that they have drawn a line under the affair. Questions linger. Nor, it has to be said, is there any end in sight to the travails of Mr Johnson, the malign gift that keeps on giving. He too will destabilise his party for months, with the privileges committee and possible police action still to come.

What are we left with? First, the renewed impression of a government running out of integrity as fast as it is of time, talent and energy. The image, despite the efforts of Mr Sunak, Jeremy Hunt, Ben Wallace and other of the more responsible members of the government, is of scandal, incompetence, division and extremism.

Second, the prime minister looks weaker than he needs to. He would not be a human being, or at least a politician, if the turbulent consequences of firing Ms Braverman didn’t play on his mind.

With a huge row over immigration looming with the imminent release of the latest statistics, the last thing Mr Sunak needs is Ms Braverman touring the television studios and Tory constituency associations denouncing the prime minister and all his works. Even in cabinet, Ms Braverman finds it difficult to stick to collective responsibility, as we witnessed during a particularly sinister appearance by her at the National Conservatism conference; unleashed and free of any inhibitions she would take pleasure in tormenting Mr Sunak.

Over the past few days, it may have become clear to Mr Sunak that his backbenchers didn’t wish to give up another (Brexiteer) scalp to some (imagined) establishment plot – a ploy Mr Johnson is also trying to make use of. So he flunked it.

Politically, the most expedient thing for Mr Sunak to do was to let Ms Braverman off with a mild public reprimand, even though it was her second breach of the code since last autumn. She will cause less trouble this way, to be sure. He does, though, look weak as a result.

Mr Sunak has placed politics before principle, and to that extent demeaned himself by not doing the right thing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments