Of all the many important elections taking place across Great Britain, by far the most portentous is that of the Scottish parliament. Depending on the result, Scotland will either be out of the United Kingdom after a few years, or else the cause of Scottish independence will be put firmly back, probably “for a generation”, to borrow a phrase.

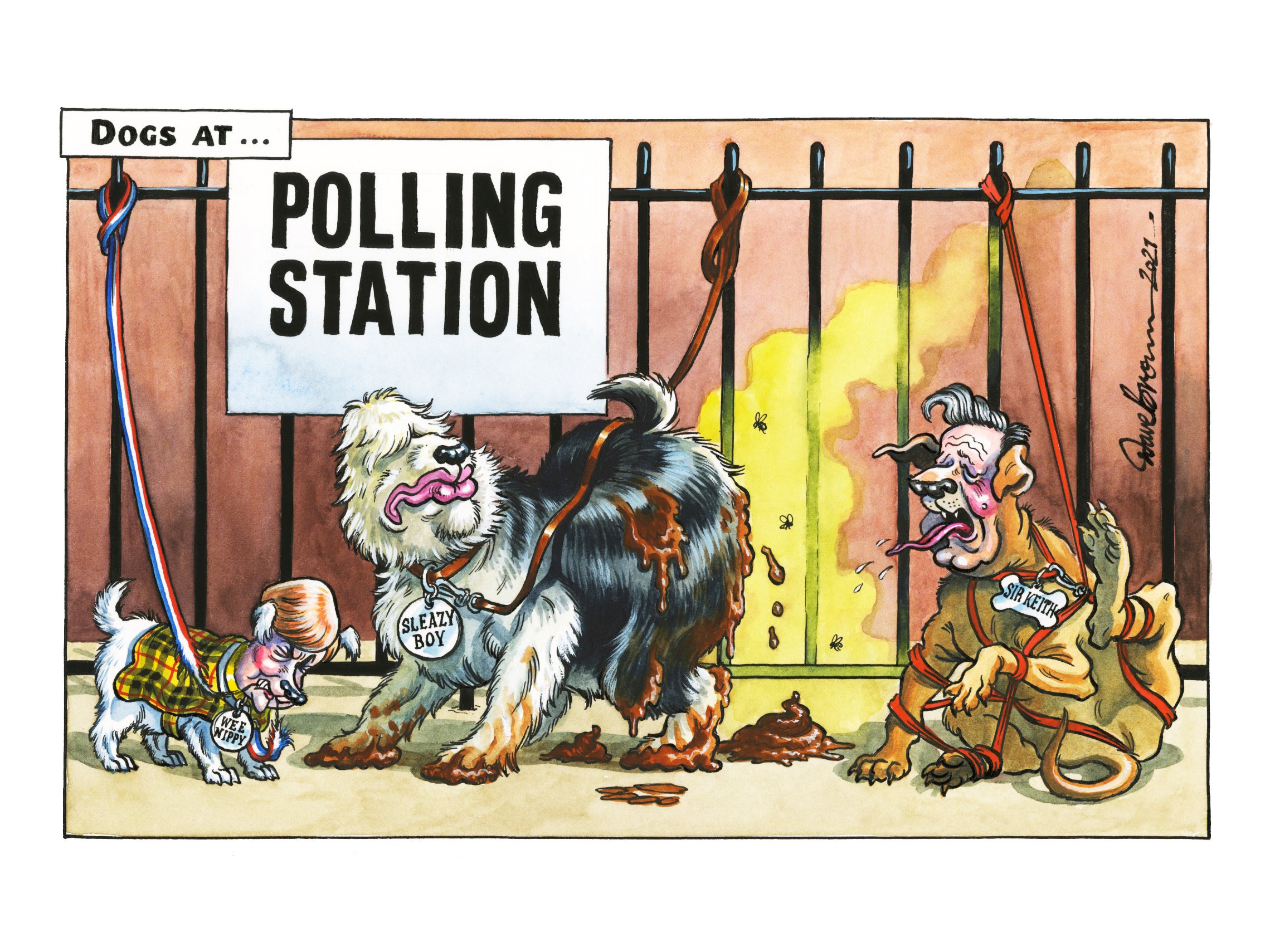

The fact that the once-dominant Scottish Labour Party and its fresh new leader will probably be stuck in third place is a mere sideshow in a constitutional drama that seems likely to dominate national politics (ie British and Scottish) for many months. The likely destruction of the breakaway Alba party will perhaps mean the end of the political career of Alex Salmond – a remarkable event, but now a mere footnote in the much bigger, wider story.

It is perfectly apparent – as it has been for months, if not years – that the Scottish National Party will once again emerge as the largest party in the 129-member parliament, and that Nicola Sturgeon will soon be re-elected as first minister. The other leaders, in their recent television debate, virtually conceded as much, pleading with the Scottish people to deny her party an overall majority in the coming election. They knew what they were doing.

The SNP is perfectly able to govern Scotland even without an overall majority, as it has done before, with the help of its Green Party allies (likely to do well) and a certain amount of compromise over legislation. The point about the SNP winning an overall majority – 65 seats or more – is that it adds to the moral and political case for a second independence referendum. This is clearly the case since the SNP has made winning a “mandate” to hold a second referendum (albeit after the Covid crisis has passed) such a feature of its campaign.

The SNP is also keen on following the powerful – and highly advantageous – precedent of 2011. It was at that election that the party, under Mr Salmond and with Ms Sturgeon as a prominent figure, broke through to an overall majority, and an all-time high in representation at Holyrood, of 69 seats.

Armed with that showing, Mr Salmond won agreement from the then prime minister, David Cameron, for a second referendum, with the Scottish parliament determining its timing (within a two-year time span), the wording of the question (subject to Electoral Commission approval), the franchise (extended to 16- and 17-year-olds), and regulations about campaign finance. Though not a binding precedent, the 2012 “Edinburgh Agreement” hangs heavy in the air.

As things stand, the experts put Ms Sturgeon and her party’s likely total between 63 and 68, leaving the 2012 precedent arguable – and particularly so by Boris Johnson, who has already made it clear that his refusal to grant a new plebiscite will be absolute and unconditional.

That, then, would leave Ms Sturgeon with the option of an unofficial referendum: something she once viewed favourably, but which she has now ruled out as a “wildcat” act. The Catalan example, which failed and was not recognised by the EU, is encouragement enough not to go ahead with such an exercise. Instead, the SNP may have to resort to other means, backed as it will be in its quest for national freedom by the Greens.

The argument would then become less about independence; instead it would be about democracy, and Scotland’s right to determine its own destiny as a political entity, if not yet a sovereign state. Ms Sturgeon could legislate in the Scottish parliament, as she has done before, and repeatedly challenge Westminster to reject Scotland’s claims. She could take the matter to court – citing among other arguments the precedent of Irish secession from the UK a century ago (where a parliamentary mandate, rather than a referendum, was enough; though violence was the real force at work).

She could withdraw Scottish cooperation from UK-wide consultative and other bodies, though Mr Johnson has already effectively done this, such is his ill-disguised contempt for the “disaster” of devolution (as he once styled it). She might even withdraw her MPs from Westminster, though it would do the rest of the UK no favours. All the way through there would be the permanent background noise of disputes about which currency to use, the hard border with England, rights to travel and work, and all the rest.

If she is shrewd – which she has proved herself to be – Ms Sturgeon will bide her time until there is a better strength of opinion behind independence in the opinion polls, though there is much impatience both in her party and in the independence movement for a swift campaign, and she too is conscious that time is running out for her to complete the political task to which she has devoted her career. The risk, though, is that she will gamble and lose, and destroy the possibility of Scottish independence for a generation.

Like Brexit, the debate about a referendum and independence will be a constant distraction, even after the Covid crisis is over. Like Brexit, the arguments are unlikely to be drawn to a happy consensual conclusion after any referendum is held – because, like Brexit, opinion is evenly divided, and the terms of Scotland’s proposed exit from the UK and entry into the EU are unknown. There is, rationally, a case for a second referendum, as there was on Brexit once the terms of exit had been determined.

Only if a referendum is held and the Scots vote to remain in the UK will the debate die down for very long. Indeed, Ms Sturgeon could volunteer a more binding, legal version of the old SNP slogan that it would be a “once in a generation” vote, though Mr Johnson is still liable to spurn anything she proposes. The constitutional status of Scotland will most likely disfigure Scottish and British politics for years. It has only just begun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments