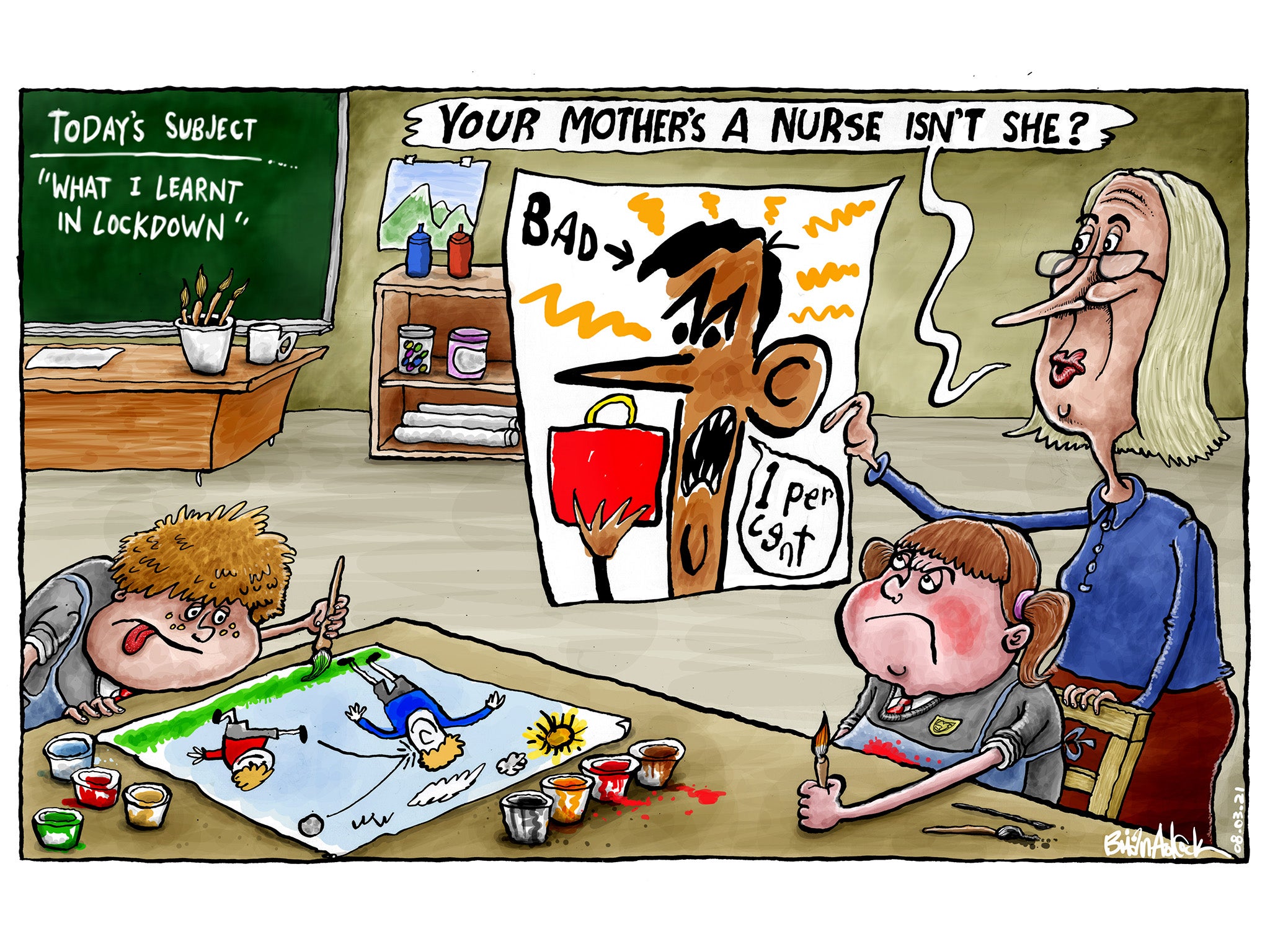

It is a milestone of huge significance. Schools in England start reopening tomorrow, while those in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland will follow shortly.

There is, of course, high symbolism for two reasons: this is the first substantial sign that the country is returning to some sort of normal life; second, it signals that the education of children is, and must remain, at the forefront of national priorities.

Substantial and reasonable concerns remain, however. As The Independent has reported, more than one-third of the public believes the government is moving too swiftly with the reopening. This caution is quite understandable, given the experience the country has had of previous lockdowns ending prematurely.

It is all the more important, then, that the process should be closely monitored and, if necessary, the plans revised. This is self-evidently about the protection of young people, but it is also about the protection of all school staff.

The reopening must be sensitively and cooperatively managed. This means that teachers and other staff who, for whatever reason, are unable to return to face-to-face duties should be encouraged to contribute in other ways. If there is evidence of new flare-ups of the virus, there should be a swift and effective response.

Beyond this, there are two things that need to happen. First, we need to draw the appropriate lessons from this dreadful experience. Many schools have managed effective home-learning programmes. It goes without saying that these have been, at best, an inadequate substitute for classroom teaching. There are many parents and children that will say aye to that. But it is equally the case that schools – and teachers – will have discovered new ways of relating to students that will be useful in the future. Necessity has been the mother of invention. Now we need to use that knowledge in a positive way.

The other task will be to make sure that no young person is put at a disadvantage as a result of a year of interrupted education. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has calculated that the likely loss of lifetime earnings that will result from a pupil losing one year of schooling is £40,000. That is massive, and profoundly disturbing.

But while it is helpful to put a number on the loss, there will be other, non-financial costs. The toll on mental health is one key burden, if a less tangible one.

This is monstrously unfair, self-evidently so for young people who, through no fault of their own, happen to be at a crucial stage of their development. But it is also a challenge to society at every level. This is not just something that schools need to tackle, for example by scheduling extra learning opportunities. The whole country must make sure that no child is left behind. That will require sensitive action by the schools themselves, but equally by universities, companies operating apprentice schemes, employers in general, and, of course, future governments.

We should all be relieved that it has become possible to reopen schools. We should hope that this can be done safely. But above all we must focus on the future of the country’s young people. That matters more than anything else.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments