The case for schools returning is strong – but teachers and pupils need to be able to do it with confidence

Editorial: Given the problems over education policy recently, there is still a job of persuasion to be done

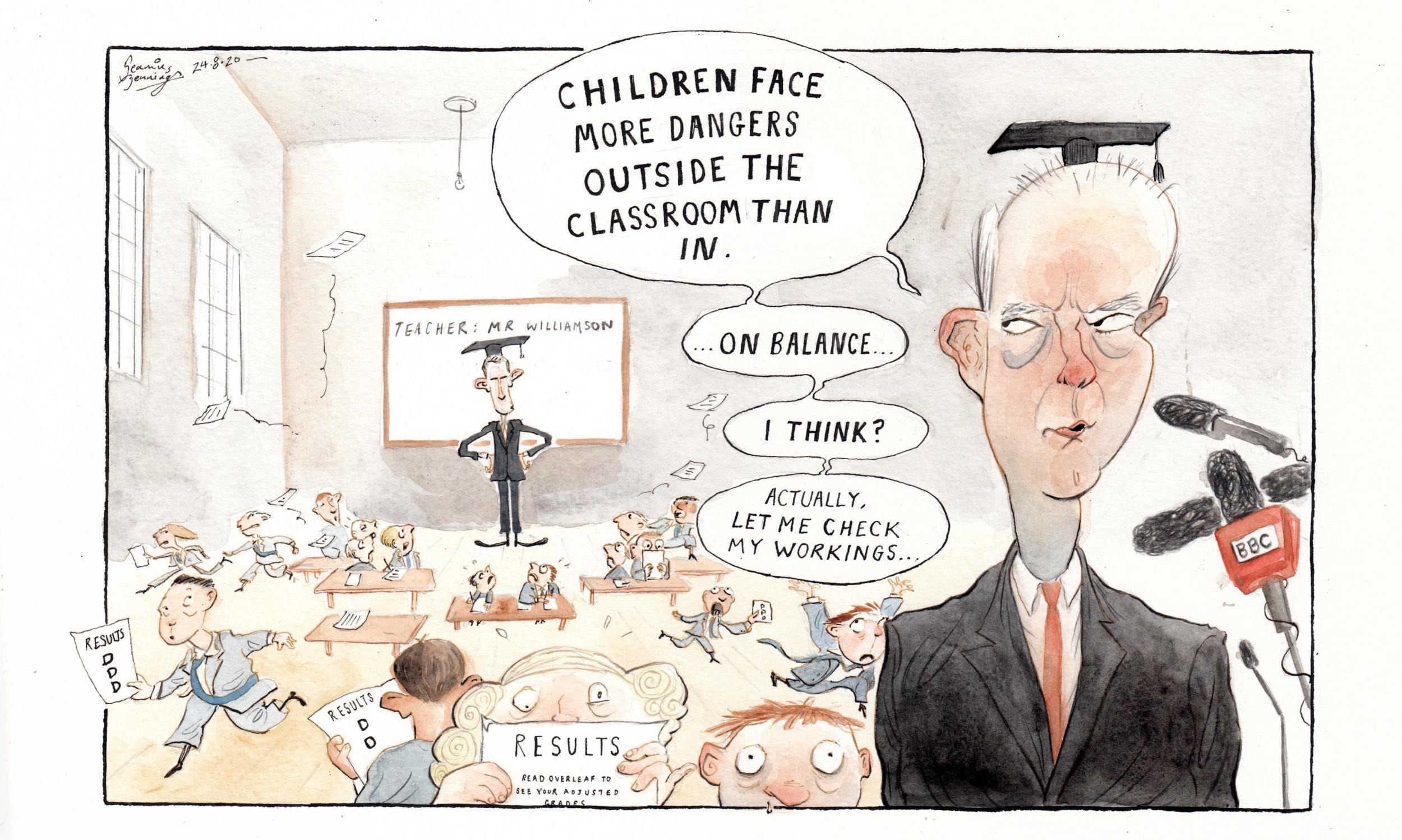

Having exhausted his modest reserves of political capital in recent weeks, Gavin Williamson, beleaguered and potentially only one gaffe away from the sack, has been forced to draw on the reputation of the still-respected chief medical officer, Chris Whitty, to reassure the public that schools are safe to return to.

After many failures on Covid-19 and the exam fiascos, no minister is likely to receive a high level of trust, as is indicated by the government’s steadily slumping poll ratings.

So it falls to Professor Whitty to tell parents that the “chances of children dying from Covid-19 are incredibly small”. As a practical man of the world, as well as science, and alert to the realities of economics, Prof Whitty also points out that pupils, in the long run, will be damaged far more by the disruption to their education and life chances than by any residual health risk from contracting the virus.

That is not to say that children are immune, or to deny that some have died from a Covid-related condition similar to Kawasaki disease. Such distressing, though rare, cases are now well documented. But advisers have to sift evidence and make a balanced argument so that ministers can decide. In this instance, it is also the only way left for the government to persuade the public to trust it.

The argument for a return to school is strong. Parents cannot easily cope for much longer trying to work and care for children at home; much economic hardship would follow if the schools were not to be reopened safely. Another cohort of students should not be put through the agonies of the exam gradings and re-gradings, and nor should employers and universities have to deal with the consequences of a broken exam system. It is tacitly accepted now that, if more lockdown measures become necessary, schools should be the last candidates for closure.

Yet there are still problems with the opening of schools. The risks to young children are low, but they increase with age; and transmission rates from child to child and from child to adult seem less well understood. How will teachers and other school staff be protected from dangers? They should not be asked to put their lives on the line, nor jeopardise the health of their families.

Not enough has been revealed about the evidence behind Prof Whitty’s judgements, and, with the stakes as high as they are, he, and his counterparts around the UK, should publish the scientific basis of their opinions. It is not enough, even for Prof Whitty, to simply declare that the schools are safe.

Teachers and parents are entitled to be treated as adults. These are momentous decisions for these individuals to take, and it is only fair that the scientists should “show their workings” as they present the answers to vexed questions. Without that there may be too little compliance, and the prospect of the state taking legal action to compel teachers and parents to do as they are told.

This may be a public health emergency, but now more than ever the country needs to be governed by consent. As we have seen through the malign influence of the Cummings effect and the decline in solidarity and social distancing, no government can combat this pandemic without the overwhelming support and confidence of the people. That includes the nation’s hard-working teachers.

School staff are right to refuse to stand aside and allow ministers and advisers to mark their own homework. There is a job of persuasion to be done, and Prof Whitty will need to do it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments