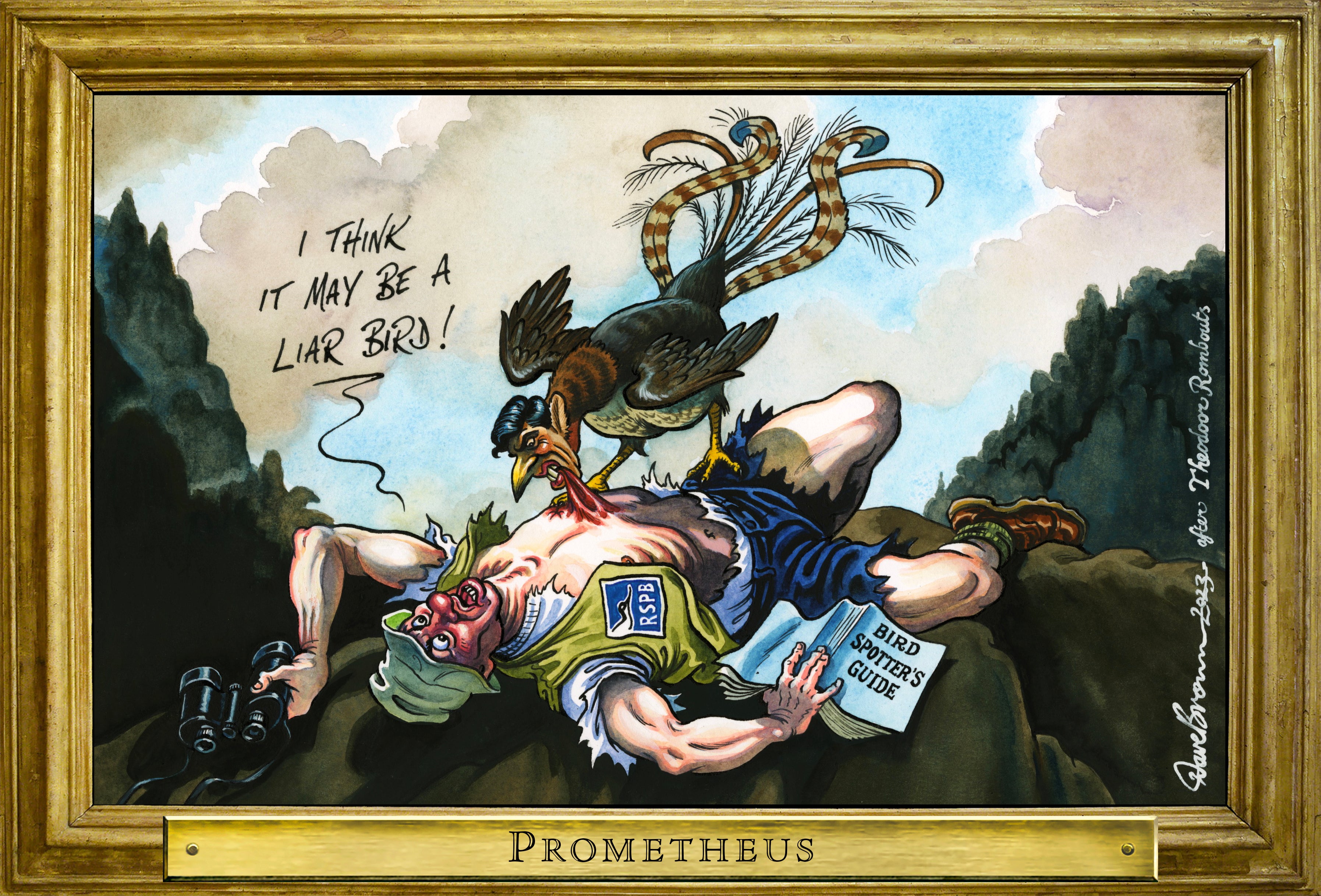

The school buildings safety scandal has exposed the shaky foundations of a floundering government

Editorial: Ministers can’t be blamed for crumbling concrete but, as they’ve known it posed a potential risk in schools since 2018, they are open to charges of negligence, complacency and incompetence

One of the many extraordinary aspects of the emerging school buildings scandal is that even now, no one – least of all worried parents – is certain which schools are affected, or how many of them are. Nor do they know the precise nature of the risks.

We do know that 24 schools in England have been told by the Department for Education to close; some 104 were already partly closed; and now, a further 50 or so are to have some buildings put out of use. This, to provide some perspective, is out of 24,000 schools in total. But the beleaguered schools minister, Nick Gibb, admits that he doesn’t actually know what the final number will be, or the extent of the consequent disruption to learning, or the cost of remedial work (beyond the fact that it is likely to run into billions).

Even more disconcertingly, the authorities in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have only just begun an audit of their own schools estate to identify where reinforced autoclaved aerated concrete (RAAC) has been used and presents a risk to life. The only comfort, given the shocking revelations, is that no child or adult has been injured as a result of structural weakness in these buildings. As bad as things are, they could have been much, much worse.

Yet the problems have been known about since at least 2018, and it has long been accepted that RAAC is present in a vast range of public and private buildings, along with roads and other structures, because it was so liberally installed between the 1950s and the 1980s. It has a normal lifespan of 30 years, though it can last longer; in all circumstances, it needs to be maintained.

In flat-roofed buildings in particular, the gradual ingress of water can corrode the aerated material all too easily, with eventual sudden unsignalled collapse being the inevitable consequence. Mr Gibb, the education secretary Gillian Keegan, and indeed the entire government may count themselves lucky that no one has been injured or killed as a result.

There are so many questions to answer, for ministers and officials all over the UK, that it is difficult to know where to start. But in parliaments across the land, the politicians who have presided over this scandal must make urgent statements – to tell the whole truth about how our schools have ended up in such a state, and explain what they propose to do about it.

When did it become evident that there was a problem in schools (and other public or private facilities, such as hospitals and motorways)? Why has the audit of RAAC been so leisurely? Why was there so little openness and transparency? Why did Michael Gove, as education secretary, cancel Labour’s school renovation projects?

If Mr Gibb’s account of the debacle is correct, then who were the experts who told ministers that certain schools whose buildings contained RAAC were safe, when it turned out this summer that they were not? Why did the Treasury not fund all the renovations that the Department for Education had requested? What are parents and teachers now supposed to do about their children’s schooling – so soon after the pandemic caused so much wreckage? How can we pay to put things right?

Such questions are vital, and ministers must be held accountable for their actions, or negligence: resignations should not be ruled out.

Yet parents – and indeed anyone concerned with the state of the nation – may be forgiven for not listening too hard to politicians’ excuses, whatever they are. All they know is that another scandal has emerged, and another public service has found itself in distress. There is a growing conviction that “nothing seems to work any more”. None of what they have heard will help to restore their faith in the government; and further damaging disclosures may yet come to light.

The roots of this scandal date back to long before most of the parents of today were born, and RAAC was a popular and uncontroversial building material, prized across the world for its strength and lightness. Ministers can’t be blamed for RAAC, but they are being suspected of negligence, complacency, or plain incompetence. Rebuilding schools, roads and hospitals is one thing; rebuilding reputations, not to mention public confidence, is quite another.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments