The Post Office must lose the right to police itself

Editorial: Anyone watching the Horizon scandal inquiry – now being broadcast daily, gavel to gavel – will see that the days of the service’s dedicated detectives are well and truly over

Another highly unexpected – but highly welcome – consequence of the ITV dramatisation of the Post Office/Horizon scandal is that the previously little-noticed proceedings of the statutory inquiry are now carried live, gavel to gavel, to a global audience.

The inquiry, chaired by retired judge Sir Wyn Williams, has been quietly and methodically going about its supremely important work since 2021, carrying forward and strengthening its remit from a previous independent inquiry. Now, the cross-examination of a single investigator from the Post Office’s security department has been given about the same media prominence as that given to the appearances of Boris Johnson and Rishi Sunak at the Covid-19 inquiry.

This is as it should be, if only as an attempt by the media and officialdom to make up for previous neglect. What befell innocent subpostmasters and subpostmistresses over a period of two decades is, after all, the widest miscarriage of justice in British history, and those thousands of people who have had their lives destroyed, and even ended, in this disgraceful episode deserve the maximum disclosure of their actual, truthful innocence.

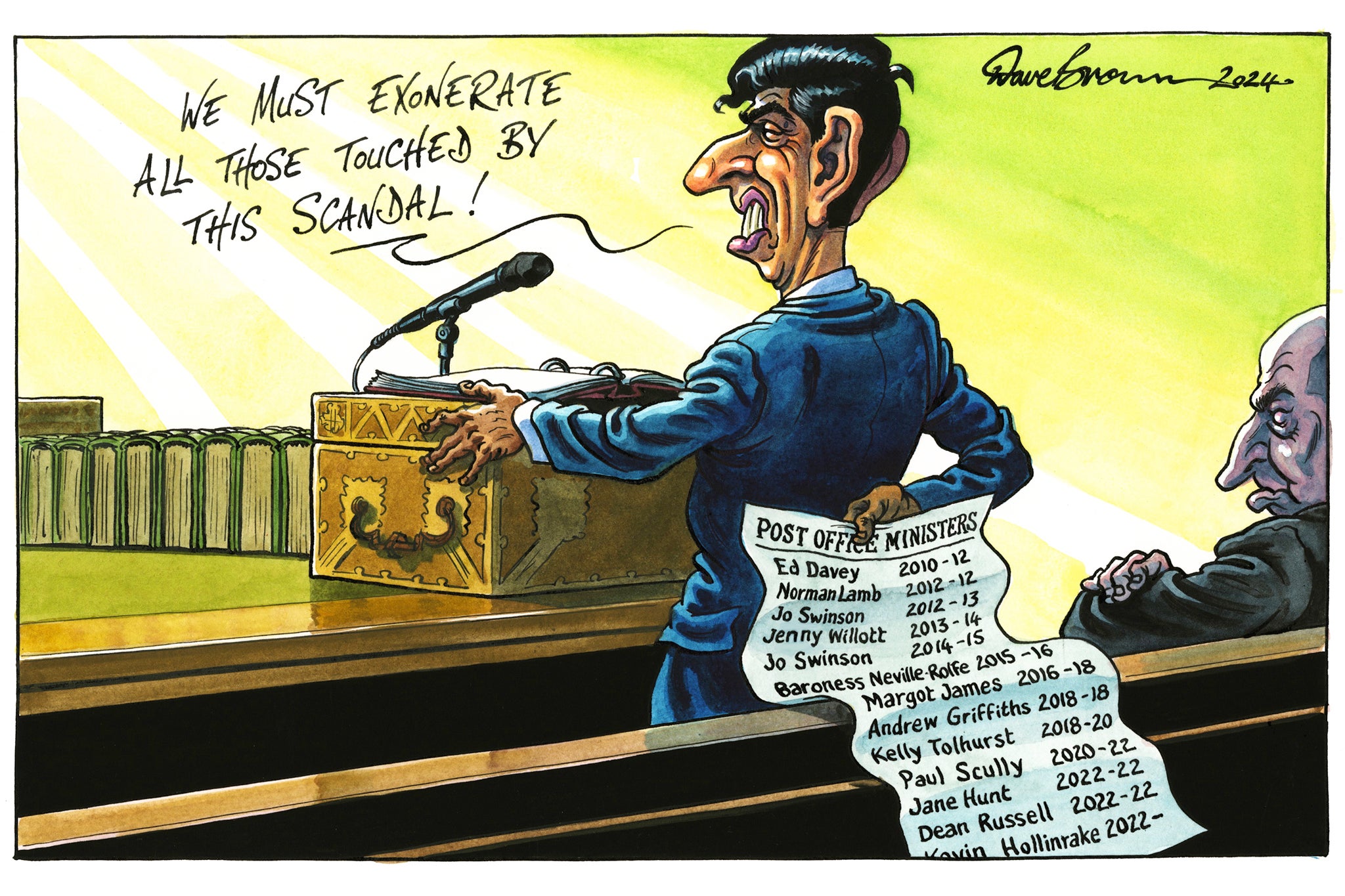

The restoration of their reputation depends on more than even an act of parliament, brought in to effectively quash their convictions, can achieve. Exoneration – unequivocal and unassailable – depends on the extirpation of any doubts in the minds of the communities from which so many of these loyal servants of the public found themselves ostracised, and among whom many still live, about what went wrong.

They, or most of them, have survived their ordeal, and now the moment for vindication in the eyes of the whole nation has to be secured. Thankfully, this process is well under way. In that context, a high-level honour for those like Alan Bates, who campaigned for justice so tirelessly, would represent a further official acknowledgement of the hurt and loss suffered entirely undeservedly. In fact, a CBE for each of the wronged public servants wouldn’t be symbolically out of place in the circumstances.

In due course, the Williams inquiry will complete its evidence-gathering, and will present its report and narrative of the whole appalling episode. Given the inquiry’s wide-ranging powers – which allow for the collation of confidential material, including recordings of conversations – the outcome is bound to be searing for the Post Office, Fujitsu, civil servants in the business department, and various accountants, lawyers and politicians involved in the story.

Next week, there is bound to be intense interest in the appearance of Fujitsu officials, both at the inquiry and in front of a Commons select committee.

Once Sir Wyn has completed his work, the authorities will be better able to pursue criminal and civil actions against those identified as potentially culpable with properly evidenced-based cases. Rightly, there will be retribution, and more progress will be made towards delivering a full measure of justice and restitution.

Those responsible at the very top of the organisations concerned, especially the Post Office and Fujitsu, have to be held accountable for their actions and pursued with the full force of the law – the bigger figures cannot be permitted to scapegoat their staff for what went wrong, whatever impression may be formed from the televised proceedings.

That said, it already seems clear that the Post Office’s own investigations department is an anachronism, and too conflicted to be allowed to continue as an investigatory and prosecuting authority – or to carry the confidence of the public.

Founded more than 335 years ago, it is the oldest prosecuting body in the world, and has a long and sometimes honourable history, including a role in investigating the Great Train Robbery of 1963. It seems to have been well suited to the days when the Post Office was an arm and an emanation of the state, and operated via pen, ink, the typewriter, telegrams, and, of course, the post.

Before the Horizon debacle, it only had to deal with around five cases of sub-post office fraud a year, and the ledgers were not too difficult to navigate; that number then jumped tenfold, and the staff were not well equipped for the scale, or nature, of the alleged false accounting and theft. Their modern software proved to be disastrously flawed.

The department is therefore demonstrably ill suited to its original remit now that the Post Office has been transformed into an independent company, albeit state-owned, in pursuit of profit rather than service, and operating in the age of the internet and AI. All of the department’s functions should be transferred to the police – perhaps in the same way that the British Transport Police operates as a specialised force, but one that compiles with normal standards of evidence-gathering and the referral of cases to the Crown Prosecution Service.

If the City of London Police can cope with the fallout from the global financial crisis, then a similar police squad can deal with thieving in the Post Office. Quaint as the idea of them is, the day of the Post Office’s dedicated detectives has been and gone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments