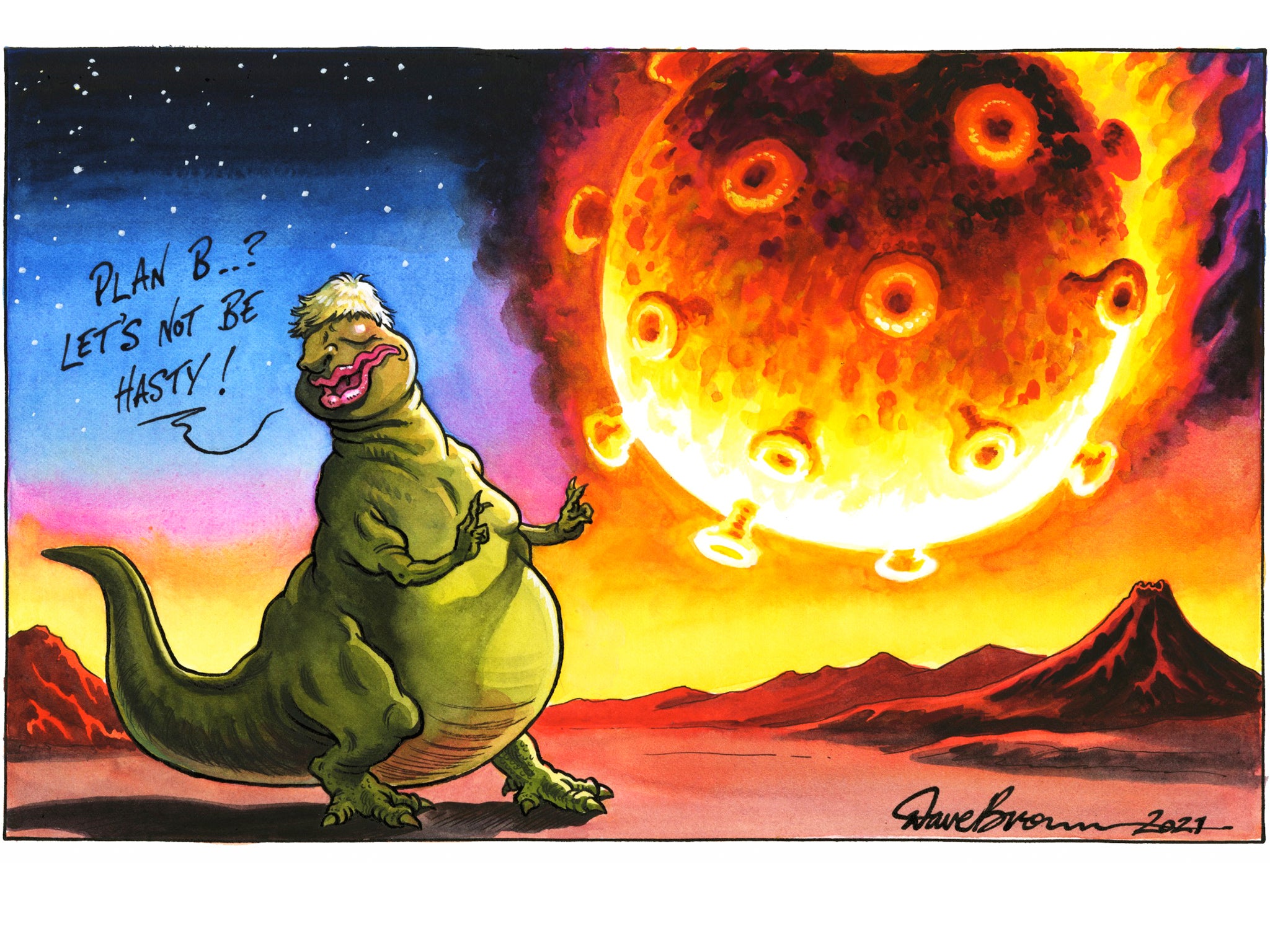

The present government line is that the start of “plan B” measures – modest, and limited as they are to masks and more homeworking – will only be triggered if the NHS comes under “unsustainable pressure”. By that time, of course, it will be too late.

Nowhere, though, is this concept of “unsustainable” defined; indeed, one health minister has specifically declined to put any specific metrics on it. He simply proclaims that the NHS is under “sustainable pressure”.

This is difficult to reconcile with the facts on the ground, such as patients, including children, waiting almost 50 hours for a hospital bed in crowded A&E departments. Perhaps trying to be helpful to his ministerial bosses, Steve Powis, medical director for NHS England, has said that the health service is “very, very busy indeed” – a masterly piece of understatement.

Others are less circumspect. The head of the NHS Confederation has said that the government is blundering into yet another crisis. The British Medical Association has accused the government of “wilful negligence” in ignoring the impending collapse in services. Now the Care Quality Commission (CQC) has added its own stark warnings, about the “tsunami of unmet need” in social care, and of exhausted staff across the care and health sectors.

According to the CQC, “the system hasn’t collapsed” – yet – but it reminds us that the NHS and care services are, for all the wonder drugs and high-tech diagnostic machinery, highly dependent on the skill and dedication of human beings, and that “the toll taken on many of these individuals has been heavy”.

It adds: “As we approach winter, the workforce who face the challenges ahead are drained in terms of both resilience and capacity, which has the potential to impact on the quality of care they deliver.”

A new phenomenon, which may well be linked at least in part to Brexit and the exodus of care workers back to the EU, is that care homes are shorter of staff than ever. With parallel shortages and higher wages being offered in retail and hospitality, and with the loss of some employees who refused mandatory vaccines, there are simply not enough people to do the work.

While hospital wards are being pushed to capacity by a rising wave of Covid admissions, albeit not as serious or in need of intensive care as in previous waves, so too are care homes finding themselves “full” because they have reached the limit of safe operation, with an artificially reduced number of carers available. This means it is increasingly difficult for prospective care-home residents to find somewhere to live and be looked after.

As happens so often, people with disabilities are being treated the worst. It has been known for a long time that people with a learning disability are significantly more at risk from Covid, but the CQC found that, over the past year, the physical health of people in community care with a learning disability was not satisfactorily considered.

Inspections of services for people with a learning disability or autism continue to find examples of care so poor that action is needed to keep people safe. Parents of such children have historically been treated poorly, and the pandemic, along with the corresponding pressure on resources, appears to have made a bad situation worse.

That, then, is what “sustainable pressure” looks like, and it is in reality unsustainable, both for those working in the health and care systems and for those who depend upon their services. It feels very much like it is only a matter of time before the spikes in hospital admissions start to visibly break the system; meanwhile, the government is engaged in a reckless gamble that it won’t happen.

This is, though, perfectly preventable, or at least containable, if only some sensible precautions were taken now: mask-wearing, “vaccine passports” for crowded events, social distancing, and working from home, for example.

None of these measures has much downside, economically or otherwise, and certainly not compared to the inevitable rushed lockdowns that will have to be imposed to save the NHS from a failure that everyone inside it can see coming right now.

As ever, the great achievement of the early vaccine rollout is being undermined by complacency about vaccinating the young, and by the lack of a vigorous programme for the administering of booster jabs. Evidently, lessons have not been learned.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments