One of the many galling statistics about the NHS crisis is that the number of people who die because of delays in ambulance and emergency care – between 300 and 500 a week – is around the same as current deaths from Covid-19 or cerebrovascular disease (stroke), and 10 times the number who perish in road traffic accidents. If it weren’t for the danger of hyperbole, it would be right to call the current crisis an epidemic.

Behind the statistics lie heart-rending stories of extremely ill, vulnerable people, often elderly, dying at home or in the back of an ambulance for lack of resolve to deal with the crisis. Although now widespread and taken for granted, this is not normal, even though it is becoming normalised.

A pensioner expiring before their time on a trolley in a corridor is no longer news in a way it would have been a few years ago. It is accepted as inevitable, almost natural. It is nothing of the sort. Nor is the scramble to get a call in to the GP first thing in the morning, and nor is waiting almost two years for treatment.

This is a manmade crisis, and one made in the corridors of Westminster, not in the nation’s crowded infirmaries. There should be a national emergency declared by ministers, for the simple reason that there is one. Embarrassed reluctance to face the reality won’t make it go away. There is a disturbing sense of drift about the near collapse of the health service, just as there has been over the strikes.

The prime minister, health secretary and chancellor are conspicuous by their absence. Steve Barclay takes to Twitter to cheerfully urge us to take a jog and recommends the excellent NHS Couch to 5k app; but all the nation knows Mr Barclay is himself taking it nice and easy on his own comfy sofa. He is a man who makes Matt Hancock look like a presentational maestro.

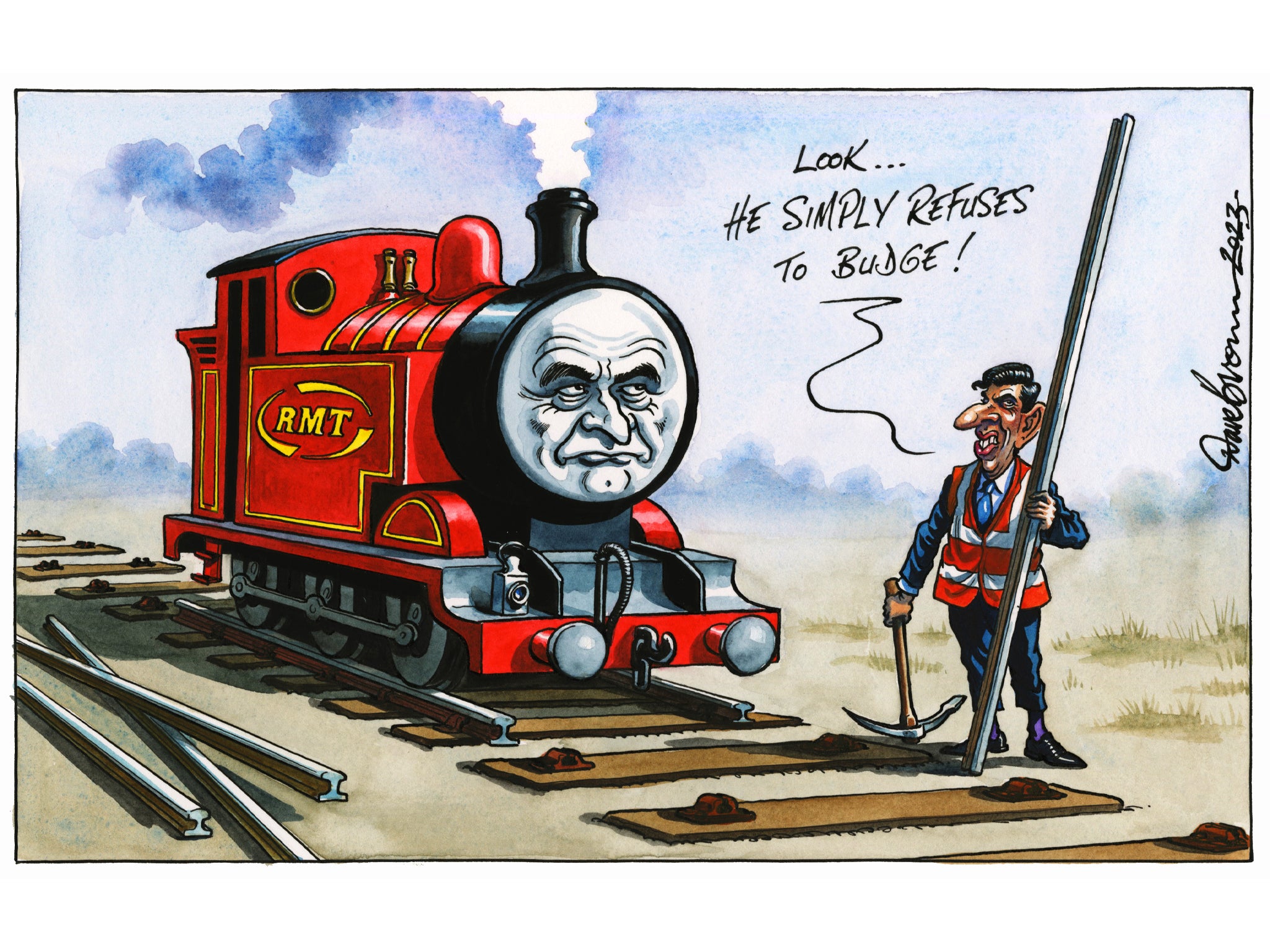

There are plenty of excuses. Industrial action hasn’t helped – but the public know who is to blame for refusing to negotiate when paramedics and nurses beg minsters to talk to them. The strikes would be called off – and lives saved – if the government bowed to the inevitable and increased the pay offer.

Of course, Covid and its post-pandemic aftermath has created unprecedented challenges. The irony is that the NHS coped better in the pandemic itself than in the following recovery. There is a clue there. During the pandemic, social restrictions and health precautions such as hand washing and wearing face coverings, and eventually lockdowns, pushed the Covid rate low enough to allow the NHS to function and treat both Covid and non-Covid patients.

Without lockdowns, the pressure on the NHS would be even greater now because even more screenings and elective procedures would have been postponed until after 2020 and 2021.

So the first step to reducing the peak of illness caused by Covid, flu and other respiratory diseases is to reduce the infection rate – hence the new UK Health Security Agency official guidance on self-isolation when ill, face coverings in crowded spaces and modest restrictions on travellers from China. Much more may be needed in the coming months if the spikes in these viral infections climb ever higher. Lockdowns aren’t on the agenda, but some modest precautionary measures should be, and so should a renewed drive to increase the rate of vaccinations.

One of the most depressing aspects of the current crisis is just how widespread the anti-vax propaganda has grown, how many charlatans are monetising people’s legitimate concerns and how some people who should know better, including one or two MPs, are being brainwashed by the hoaxers.

A state of national emergency in the NHS would not solve the crisis overnight, but it would start to put things right. Above all it should concentrate minds in Whitehall and in the devolved administrations about how the post-Brexit NHS and social care staff shortage can be fixed in the coming months. Even a huge cash injection now would do little to put skilled medics on wards and in GP clinics.

It is a long-term failure of personnel planning, once highlighted and now addressed by the chancellor, Jeremy Hunt, and a short-term cost of Brexit. We know who to blame but it’s not obvious who in the present administration is willing and able to put things right.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments