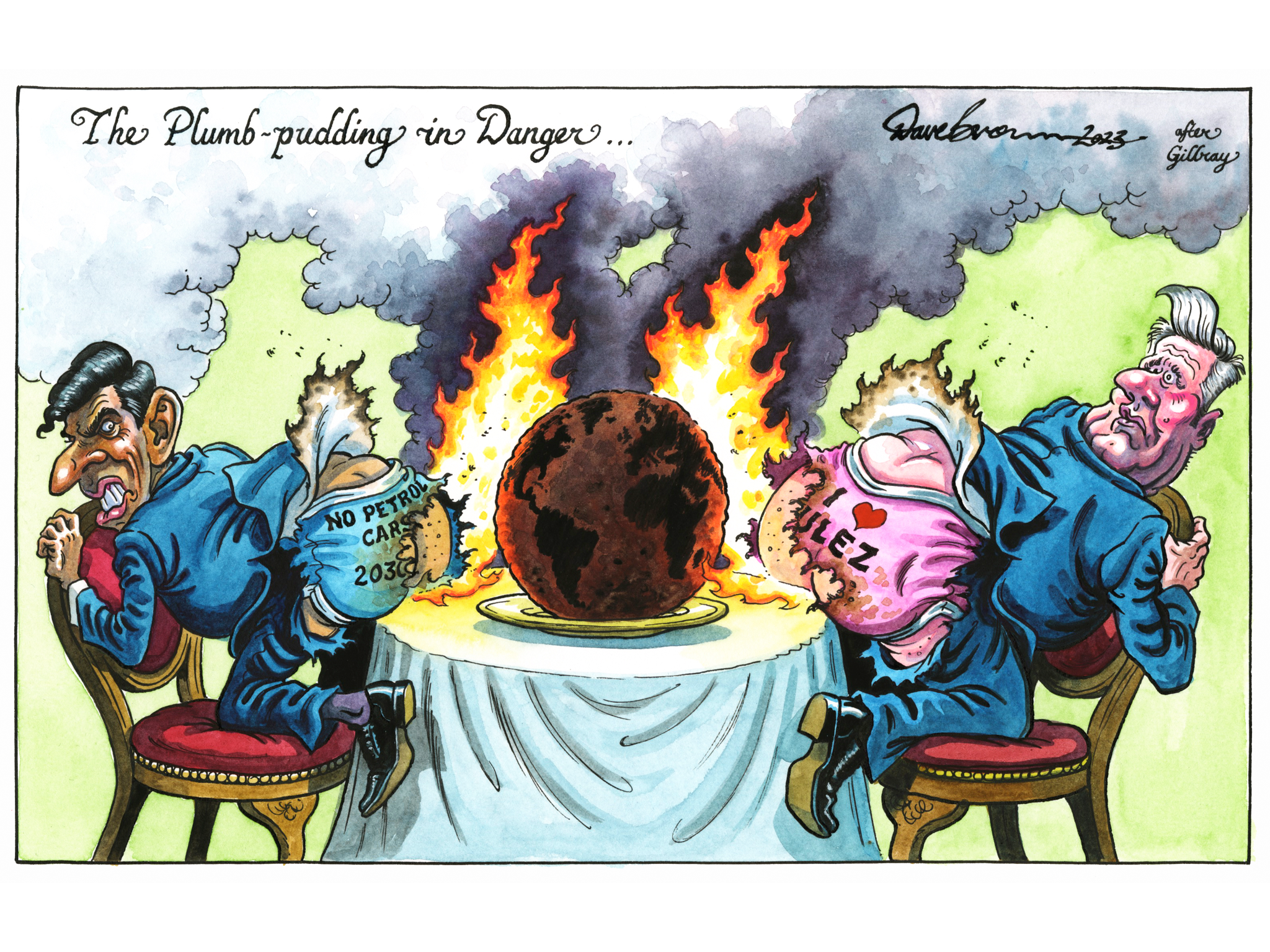

Almost a week has passed since the Uxbridge by-election, and it remains a catalyst for at least a flirtation with abandoning green policies by both main parties.

Downing Street is still letting it be known that the Tories’ extremely narrow victory, in a seat considered safe enough for the prime minister last time round, is prompting considerable thinking on whether there might be more electoral mileage to be found in turning their backs on the green agenda.

Sir Keir Starmer and Angela Rayner, too, have responded not by sticking up for London mayor Sadiq Khan, who is expanding London’s ultra-low-emissions zone entirely in keeping with the plans of his Tory predecessor and the Tory transport secretary, but by distancing themselves from the policy, and questioning whether its implementation might be done in a different way.

This is what has become known as “greenlash” politics, and it’s a fool’s game. In the days since Uxbridge, Rishi Sunak and his spokesperson can’t seem to come to the same conclusion on whether, for example, the commitment to banning the sale of new petrol and diesel cars by 2030 is still in place. This follows the very public announcement of a £500m state subsidy of Jaguar Land Rover parent company Tata’s plans for an electric battery plant in the UK.

To spend half a billion pounds of public money on car batteries one week, then threaten to scrap the legislation that underpins the demand for them the next, is a strategy that it would be too generous to describe as short-termist naivety: it would be sheer stupidity.

Michael Gove has been on the radio, but he was unable to say what should stay and what should go. The 2030 deadline on car batteries is, he says, “immoveable”, but the forthcoming ban on gas boilers being fitted into new-build homes, and a complete ban on them after 2035, should, he said, be “reviewed”.

It is extremely unclear what is meant by that, not least because watering down the commitment to achieve net zero by 2050 would require new legislation. The government has already lost one High Court challenge on its commitment to net zero, which is legally binding. Undoing it would require more than a few spicy comments in a media interview.

There is no doubt that this discussion has been prompted by Uxbridge. It is especially depressing, therefore, that the Ulez issue has almost nothing to do with net zero. It is about air quality in London, which has been linked to thousands of premature deaths. It is asking Londoners to contribute, not to any sort of global effort to stop Sardinia from burning, but to cleaning up their own air.

The shoddy politics around it concern whether Mr Khan really does want to clean up London’s air, or whether his plan for Ulez expansion is, at least in part, motivated by a need to recoup losses to his operational budgets. In reality, it is probably both, but intellectually, it cannot be. Any honest attempt to encourage people to switch to alternative means of transport by applying punitive taxes can’t carry within it a hope to make money. It can only be one or the other. There is a legitimate political debate to be had there, but it does not concern net zero.

More to the point, greenlash politics might have some base appeal to a prime minister who is instinctively non-interventionist, neo-Thatcherite and, if his unhappy colleagues are to be believed, not interested in green issues.

But green scepticism – or green cynicism – is not electoral dynamite. It’s electoral kryptonite. In last year’s Australian elections, under a system all but identical to our own, candidates calling themselves the “Teal Independents” made a decisive contribution, unseating prominent politicians from the governing party by promising more ambitious targets on climate change.

There is only one direction of travel. A moderately surprising by-election has already been superseded in the news by the evacuation of tens of thousands of British holidaymakers from Greek and Italian infernos. It is a scientific certainty that these problems will get worse before they get better, for a very long time indeed.

The public, generally speaking, want more done on climate change, and faster. The constituency that does not is already small, and will only shrink with the passing of time. Appeasing it will be the shortest of short-term fixes, and will backfire just as fast.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments