Nelson Mandela's place in history

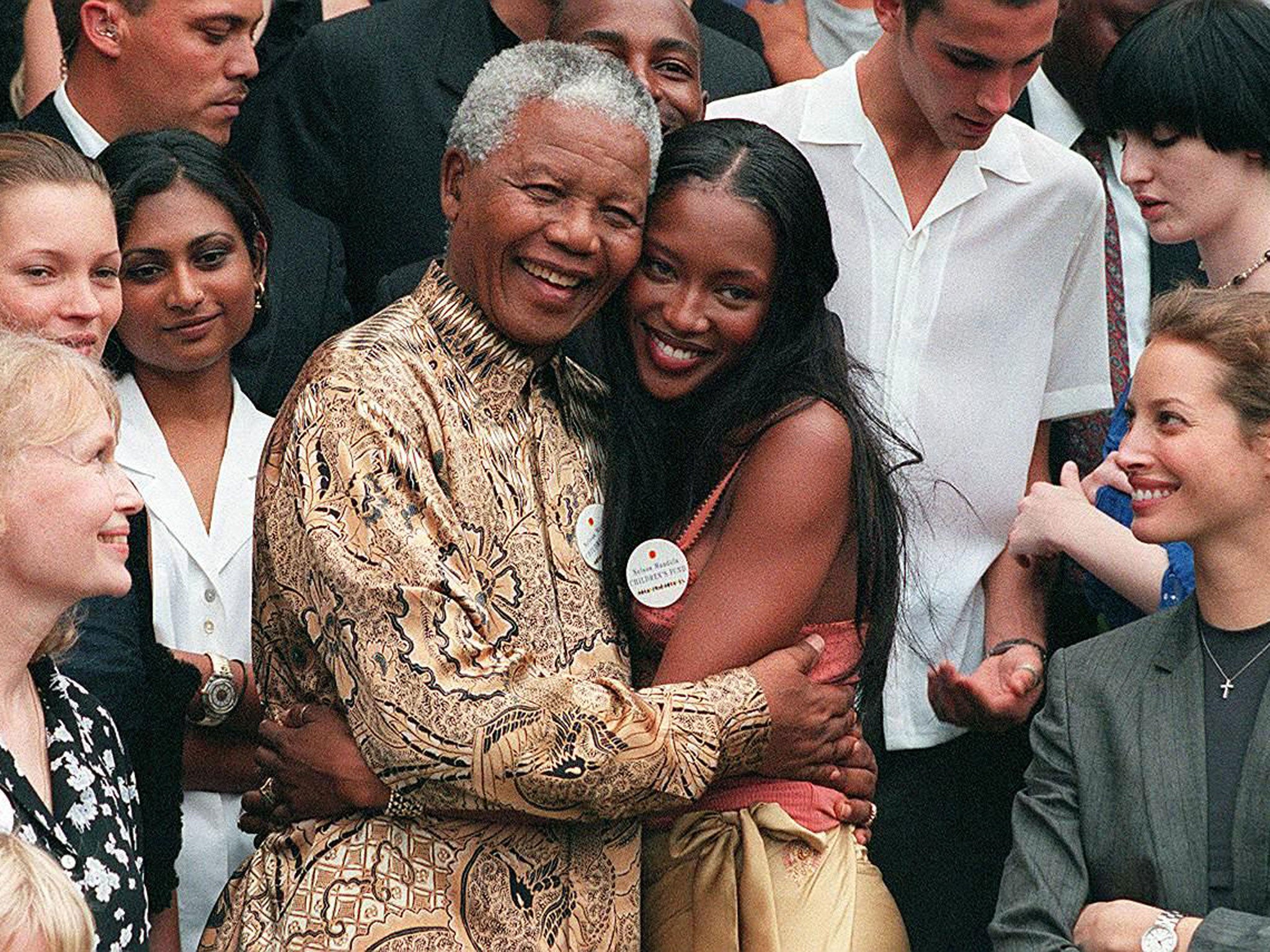

He was the world leader all others looked up to

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.We humans can generate unspeakable evil. Our species’ redeeming grace, however, is its equal ability to produce people who prove that no evil is too great to overcome. Of such individuals, none throughout the blood-soaked 20th century was more remarkable or more indelible than Nelson Mandela, who died last night at the age of 95.

In bringing to an end South African apartheid, Mr Mandela not only dismantled a system that he rightly described as moral genocide. He laid the foundations of a new country, and turned the entire process into a triumph of forgiveness and peaceful reconciliation that may be unparalleled in modern human history. In doing so he established himself as the world leader all others looked up to – a byword for morality, humanity, statesmanship and vision, and an object of reverence whose legend only grew as he aged.

From the outset Mandela was a natural leader, with an internal discipline and sense of destiny that enabled him to withstand decades of imprisonment by his opponents. A lesser man – and with reason – might have remained forever embittered at the white regime that held him behind bars for 27 years. But while Mr Mandela to the end of his days remained a revolutionary, the man who entered jail as an insurrectionist emerged as a statesman of extraordinary political skills and surpassing dignity, seemingly without a shred of vindictiveness towards his oppressors.

You have to delve deeper into 20th-century history to find anyone who bears comparison with him: Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, men who, in a violent world, accomplished what they did by non-violent means. Like them, Mr Mandela possessed the ability to bring out the best, rather than the worst, in people. Like them he inspired, in Abraham Lincoln’s words, the better angels of our nature. Like them, he became a secular saint, a moral conscience for his times.

If anything, the trajectory of his life – from lawyer, to armed resistance leader, to prisoner, to the position of both moral guide and political leader of his country – was even more extraordinary. Racial divides have produced some of history’s greatest horrors. But Mr Mandela proved they could also be peaceably overcome. He gave the lie to Bismarck’s famous assertion that great issues could be resolved (and by extension nations born) only by blood and iron.

The hagiographical shroud that settled around Mr Mandela could mask his acute political skills, his mix of patience and quiet determination, his grasp of the arts of persuasion and his understanding of the importance of symbols. Never was this latter quality more in evident than when, at the opening of the 1995 Rugby World Cup on South African soil, he personally donned the green and gold Springbok shirt to encourage black South Africans to get behind the team – and the sport – that embodied white supremacy. This new nation was forged, if anywhere, not on the battlefield but in a sporting arena.

Like every human being, Mr Mandela was not perfect. His temper could be fierce, and he managed his family life a good deal less successfully than he did his country. But his failings were tiny when set against his virtues. Yes, the “pedestal of hope” – to borrow the phrase of his successor, Thabo Mbeki – on which Mr Mandela placed the new South Africa is currently wobbling. Vast disparities of wealth remain, the country is plagued by poverty and violence, and the political system has become ingrown and corrupt. But it remains the emerging giant of the continent, still of huge possibility.

Just think what might have happened had there not been a Nelson Mandela. Sooner or later, apartheid, like Nazism or Soviet communism, would have disappeared. But its passing might so easily have led to a racial inferno, begetting hatreds and revenge lasting generations. Thanks to Mandela, that did not happen. For that alone he will forever occupy an unmatched place in the history not just of his native South Africa, but of the world.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments