The Liberal Democrats couldn't do much more in this election to garner support – their fate was sealed in the Coalition

Tuition fees – where Jeremy Corbyn is comprehensively outflanking them – remains a sore point among the middle-class types the Lib Dems traditionally appeal to

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.By any measure, the Liberal Democrats ought to be making more headway than they have in this election campaign. Their manifesto, launched today, is full of mostly sound ideas, many of them trailed in the days and weeks before (and less haphazardly than were Labour’s plans).

The standout commitment, to give the British people a final say on the eventual terms of Brexit, is in fact something they have been talking about almost since the votes in the last referendum were counted. As an expression of democratic principle it is unassailable. No one voted to be poorer last June, and no one necessarily voted for the kind of hard Brexit that the Conservatives are now proposing as a very real possibility.

If the UK cannot secure terms that are at least as good as those currently available – a high probability – and which may even be disastrously worse, then the voters must be allowed to consent to the policy, given that it is they who will pay the price and bear the hardship in the years ahead. Even if Theresa May and David Davis were able to secure an unambiguously better deal than exists under full EU membership, the people, Remainers and Leavers alike, still deserve an opportunity in principle to give that final assent. A “take it or leave it” vote in Parliament is no substitute for that.

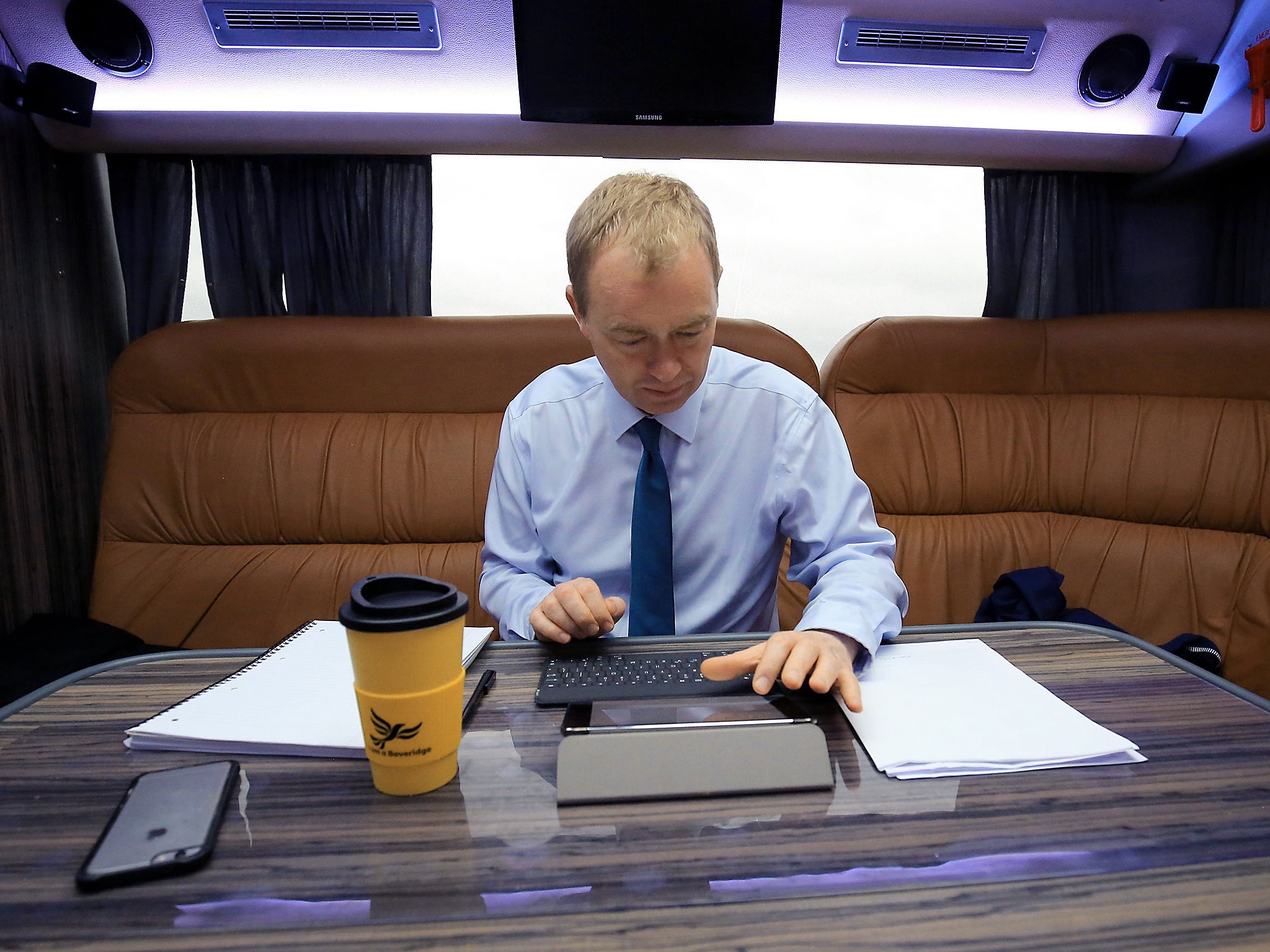

Given, too, that almost half of referendum voters wanted to stay in the EU, with a significant proportion feeling passionately about it, Tim Farron should by now be riding high on a wave of Europhile enthusiasm, as he is the only national party leader to offer an unequivocally pro-EU message (not counting almost every ex-party leader from Sir John Major to Tony Blair to Nick Clegg). Yet the expected wave of Europhilic support has not materialised, or, rather, it has not been sufficiently rallied.

Like Labour, Mr Farron can also boast policies that are popular with the public, as least according to the opinion polls. Restoring the pupil premium in schools, for example, is one such, as is the pledge to offer free school meals for all. Admittedly the pledge to raise income tax by one penny in the pound is less attractive than Labour’s clever tactic of limiting rises to the demonstrably “rich”; but at least the Liberal Democrats can be said to have a more realistic view of how they would fund their commitments than either Labour or the Conservatives, with what appears to be a more sustainable split between increases in various taxes and state borrowing respectively. The British people, whether they like it or not, may now be coming to realise that their taxes are going to go up whoever ends up in Downing Street.

Elsewhere, the Liberal Democrats revert to type as the party that pioneers policies the others deride, and which the public look quizzically on, but which eventually find their time. In the past it was, indeed, Europe, but also apparently eccentric ideas about home rule for Scotland and Wales, and LGBT rights; now it is legalising cannabis, with the added benefit that levying a tobacco-style duty on a regulated trade would bring in £1bn a year to the Exchequer. More important, it would release hard-pressed police officers to pursue more damaging criminally activities, of which there is no shortage. Other policies, such as the ban on the sale of diesel cars by 2025 or the immediate target to build 300,000 homes a year, need some more work before they can be said to be entirely practicable and convincing.

So why are the Lib Dems stuck on about 10 per cent in the polls, a little up on the last general election, but a very poor showing compared with their strength under previous leaders? At this rate they will be lucky to increase their presence in the House of Commons, and may even fail to bring back talent such as Sir Vince Cable and Sir Simon Hughes. One answer is that the party Mr Farron leads is still not entirely being given a hearing – nor entirely forgiven for its part in the 2010-15 Coalition with the Conservatives, the denouement of which saw them decimated at the hands of their supposed political “partners in government”. Tuition fees – where Jeremy Corbyn is comprehensively outflanking them – remains a sore point among the middle-class types the Lib Dems traditionally appeal to.

Second, the Liberal Democrats are subject to a typical squeeze as the voters conclude once again that a vote for them is “wasted” in most circumstances. The election has become polarised around the leadership qualities of Ms May and Mr Corbyn. Unlike in the 2010 election, there will be no TV debate to trigger a Cleggmania-type phenomenon. Third, Mr Farron himself is too new in the post to have made sufficient impact with the voters. Like most of his predecessors, he will need time and a couple of election campaigns to build up his profile.

Yet these explanations smack of excuses. These are volatile, turbulent times. The Prime Minister herself put the focus of the election on Brexit, and has tried to keep it there. That should have helped the Lib Dems with their unequivocal message and appeal to Labour and Conservative Remainers to vote tactically on this transcendent issue. At a time when the Labour and Conservative leaderships are taking their parties to the extremes, despite some slightly bizarre political cross-dressing from time to time, the Liberal Democrats ought to have the progressive centre-ground all to themselves. In 1983, with which this year is so often compared, the SDP-Liberal Alliance almost beat Michael Foot’s Labour Party in votes. No one thinks that the Lib Dems could eclipse Labour on 8 June.

Mr Farron, in his foreword to his party’s programme, says Britain is “optimistic, good-humoured and confident”. So it is, and so is he, and energetic and engaging with it. Yet it is too tempting to imagine what a more charismatic leader than Mr Farron might have been able to do with the ball at his or her feet.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments