Tricorn hats, Beefeaters, Georgian carriages and heraldic tabards are rarely glimpsed on the streets of London in the 21st century. Yet the sumptuous colours, coruscating gems and rich fabrics are what the public expect from ceremonials such as the state opening of parliament, even if the rest of the world finds the Ruritanian display somewhat bewildering.

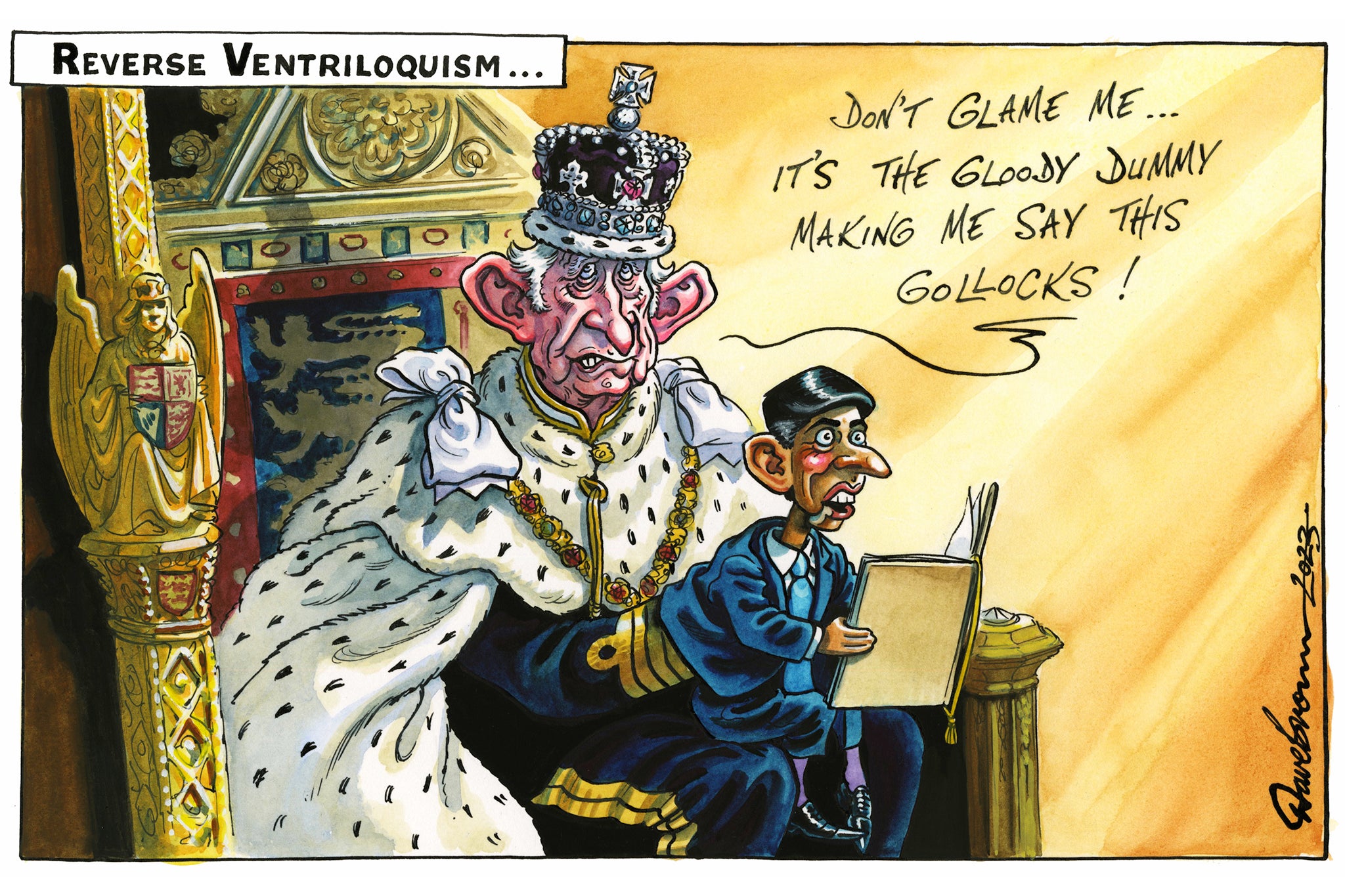

Charming as the display of post-imperial grandeur was, however, it stands in stark contrast to a less-than-majestic and underwhelming King’s Speech.

The legislative programme – for what must surely be the last months of this lengthy spell of Conservative government – isn’t going to move the political dial.

Looking at the opinion polls, it is certainly poignantly ironic that the phrase “long-term decisions” crops up so often in the text. The liberalisation of new oil and gas licences, for example, would soon be repealed by Labour if they returned to power.

Some of this lack of impact is inevitable. There is not the time now for Rishi Sunak’s administration to launch major pieces of legislation, given the fractious nature of his party and the time it would take to get more contentious measures through both Houses of Parliament.

By around this time next year there will be another King’s Speech, and most likely one written by Keir Starmer and Labour.

So, the last opportunity has passed to deliver on the bullish hopes and ambitions contained in the party manifesto in 2019. Many of the “cakeist” promises were unrealistic at the best of times and the rest were crushed by the Covid crisis, the economic damage wreaked by Brexit and the subsequent inflation. So what is left in the only King’s Speech for this parliament is a series of mostly consensual measures that will largely win qualified support from the opposition.

But while there is little space for Mr Sunak to legislate to create “dividing lines” with Labour in the coming months, they are not entirely absent, and the peculiar brand of “virtue signalling” required to appease the right of the party is indeed still in evidence. Thus, there will be tougher sentencing conventions for murder and rape, such that “life means life”, an old Tory promise at last fulfilled, “early” release for convicts will be scaled back, and judges will be given clearer discretion to compel prisoners to attend court for sentencing.

These all beg some practical questions about implementation, not least how prison governors will be able to keep order if there are no strong release incentives for the inmates to behave; and how judges can prevent terrorists from using court appearances for propaganda purposes.

A more practical point is that our jails are already so overcrowded that longer sentencing for the most serious offenders will necessarily mean shorter sentences for others. The justice secretary, Alex Chalk, is already experimenting with early release and home curfews, a move that takes the edge off the “tough on crime” image.

Reforms to leasehold, an update to investigatory powers, restrictions on smoking, a new framework for autonomous vehicles, and the banning of live transport of cattle are all the kinds of laws that any government of any party should be congratulated for – but won’t pay huge political dividends for the Conservatives.

Neither should their cowardly decision to abandon the Conversion Therapy (Prohibition) Bill. For the time being, assuming Labour pick it up again, it will remain legal for people to practice this discredited practice of “conversion therapy” on young people – widely condemned by medical professionals. It may appeal to the few Tory activists who have their own prejudices on the subject, but it will repel many in the wider community.

As so often with “speeches from the throne”, what is omitted can be as significant as what is included.

It is regrettable that there were not even modest moves on mental health and social care – surely causes that demand “long-term decisions” – and nothing on education or health. Artificial intelligence, again a challenge that needs long-term support, was also curiously absent from the bill – even though a cross-party consensus could easily have been constructed around permissive regulation.

Elon Musk, the prime minister’s new best friend, might have been happy to offer the benefit of his wisdom to ministers and the parliamentary clerks.

There were some small mercies among the legislative omissions though. Suella Braverman’s characteristically impulsive proposal to ban tents for the homeless appears to have been vetoed by No 10, and the prime minister hasn’t been foolish enough to try to exit the European Convention on Human Rights.

It is scant satisfaction though. This was a fag-end King’s Speech from a fag-end government. It is perhaps appropriate that tightening up of sales of tobacco may end up as the abiding legacy of this session of parliament.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments