On Thursday, voters across Britain will be able to pass some form of judgement on those who govern them. This is a bumper crop of elections, given that so many have been held over from last spring because of Covid. As the results are released in the coming days, the statistical feast will give the psephologists and the political classes plenty to digest, analyse and spin.

Polls are being held for parliaments in Scotland and Wales; mayoralties in the West Midlands, Cambridgeshire, Liverpool, Greater Manchester, London and elsewhere; English local councils; police and crime commissioners and others.

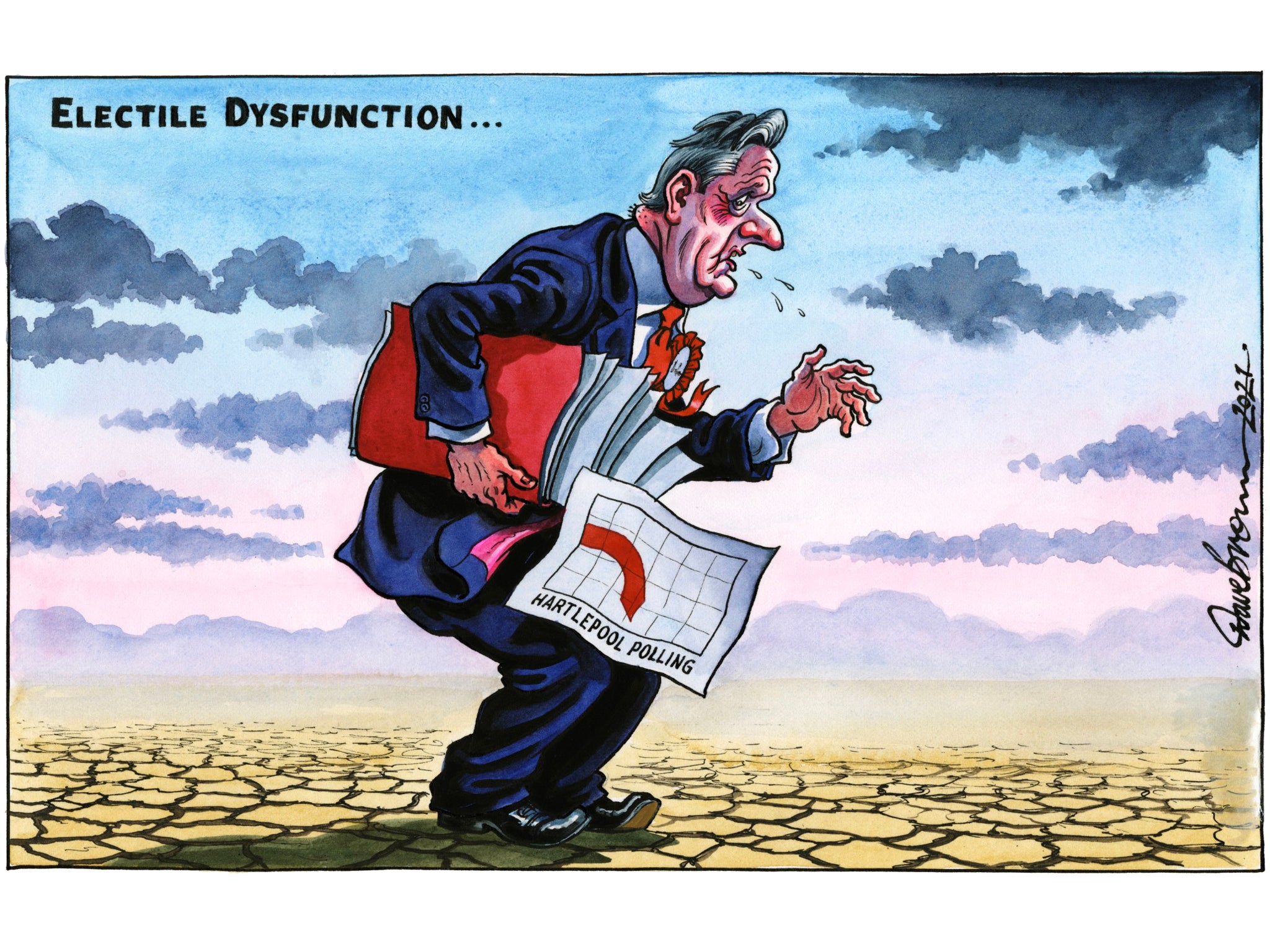

Yet disproportionate interest is already being focused on the single parliamentary by-election in Hartlepool. According to the opinion polls, it seems as though the Conservatives will capture the seat, which has traditionally been Labour. It will, no doubt, be gleefully seized upon by Boris Johnson and his allies as proof that that the public really doesn’t “give a monkey’s” about the allegations of sleaze, nor past mismanagement of the Covid crisis, and that Labour’s “red wall” remains vulnerable to what the prime minister used to refer to as his “people’s government”.

This would be only partially accurate. In truth, the Hartlepool by-election will represent the last knockings of the December 2019 general election – which seems a political lifetime ago – rather than some signpost for the 2020s.

Back in 2019, when Brexit was the dominant issue, Nigel Farage and the Brexit Party were still a power in the land. In Hartlepool, Richard Tice, a Brexit Party bigwig, grabbed a respectable 25.8 per cent of the vote, and probably deprived the Conservatives the chance to overturn another once-safe Labour seat.

Of course, Labour “should” win the seat, given the government’s overall performance in the last year and a half or so; but two obvious factors will prevent that, and gift Mr Johnson his propaganda prize.

First is the stunningly successful Covid vaccine rollout. No matter that much of that is down to the dedication of the NHS and the scientists and production engineers in universities and pharmaceutical companies globally, Mr Johnson is making the most of the triumph, and the electorate seems inclined to give him at least some of the credit for it.

Voters may also be receptive to the line that, had the UK remained in the EU, the country might not be in the fortunate position of being able to debate an earlier exit from lockdown and where to go on holiday. There is no doubt that the government’s misjudgments in 2020 cost lives and angered many, but now that Dominic Cummings is gone and the vaccine is here, there is a more generous assessment of the record.

Second, the Labour Party is having to live down the errors of the Corbyn era. Sir Keir Starmer says, quixotically, that he takes “full responsibility” for these election results, but he should not do so. Whatever the merits and rationale for the Corbyn experiment of 2015 to 2020 – and despite the near miss of the 2017 general election – by the end of 2019 it had lost the appeal it once held for the swing voters of Britain. No opposition leader, and especially not in the strange distorting conditions of a pandemic, could be expected to secure such a revolution in their party’s fortunes.

That said, if Labour fails to at least hold on to the vote share it had in 2019, and fails to make any progress in the rest of northern England and in places such as the West Midlands and, above all, Scotland, then its leader will need to use those disappointments to remind his followers of the sheer scale of the task ahead. If only in that sense, a poor Labour showing might be a blessing.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments