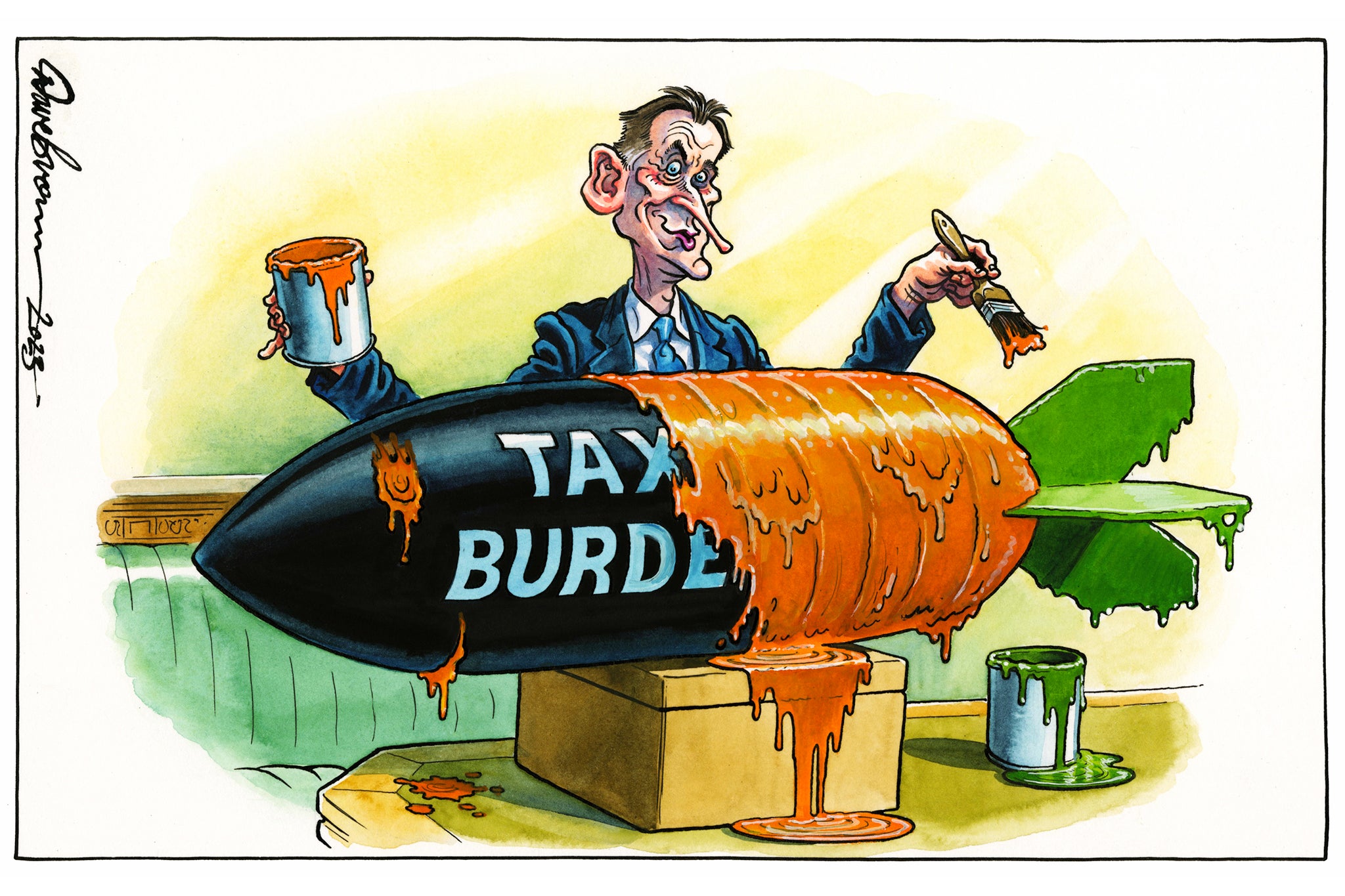

Hunt has relied on smoke and mirrors – and the voters will see through it

Editorial: The assumption among many will be that by around this time next year, it will be Rachel Reeves in No 11, and whatever Jeremy Hunt has planned will be subject to change anyway

In today’s autumn statement for growth, our choice is not big government, high spending and high tax because we know that leads to less growth, not more.”

The chancellor’s words were couched in impeccably Conservative language, and he is obviously right that economies do indeed tend to struggle over the long term under such onerous conditions. The problem, as the analyses from the independent Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) and other sources soon made clear, is that, despite appearances, Mr Hunt is in fact the chancellor in charge of a big-government, high-spending, high-tax administration.

The shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves pointed out that prior to this statement, over recent years, “the government had already put in place tax increases worth the equivalent of a 10p [in the pound] increase in national insurance”. Mr Hunt, for all his boasts, has actually only given 2 pence in the pound back to people. That is the essential context of a Budget that is, more than most, a fine example of using smoke and mirrors for the purposes of presentation.

So, will the voters see through Mr Hunt’s promises? Not necessarily, leastways immediately, and given that the still-parlous state of the public finances gave Mr Hunt such narrow space for manoeuvre, he made the most of the modest opportunity presented to him. At this stage in the electoral cycle, nothing else should be reasonably expected of any chancellor of any party, and the manufactured pre-election boom and package of tax cuts is a long and time-honoured political tradition.

It would be churlish to simply dismiss the measures as mere trickery. Mr Hunt did the right thing and increased the old age pension and universal credit by the appropriate inflation rate, despite the cost. The bigger-than-expected reduction in national insurance will be worth around £450 a year to the average wage earner; the adjustments for the self-employed should yield a similar benefit. There may well be more of the same in the spring Budget.

The two tranches of extra cash will be in bank accounts by polling day and, as a stealth tax, the freezing of thresholds tends to be forgotten. In the private sector, though not elsewhere, many have received pay rises that have kept up with price inflation. It is perfectly possible that the novelty of reductions in direct taxes for the first time in years (aside from the Liz Truss/Kwasi Kwarteng false alarm) might well help with Mr Hunt and Rishi Sunak’s narrative. It is one that should be familiar – the sacrifices made to pay back the debt run up because of the pandemic and energy crisis, and to tame inflation, are at last coming to a conclusion. Public finances have turned a corner, inflation has been halved, the economy is returning to growth and the tough decisions on tax and spending made for the long for the long term are being vindicated.

Or perhaps not. The cost of living crisis is far from over. Interest rates are going to stay higher for longer than previously assumed because inflation is likely to prove tougher to cut in half another time round. House prices will tumble by 4.7 per cent next year, according to the OBR, and the energy price cap, as well as rail fares, may well go up in January – eroding (if not wiping out) the national insurance cut. Given the fairly paltry sums the chancellor has devoted to improving public services, the perception of struggling schools and hospitals will probably persist. Besides, many households haven’t yet adjusted to the shocks of the past two years. To use the fashionable phrase, the “lived experience” of families will be uncomfortably at odds with Conservative Central HQ propaganda.

Nor will many decent folk be impressed by the harsher edges of Mr Hunt’s Back to Work campaign. There is already a great deal of fear among people who depend on their living allowances and carers. Stopping the only income of someone blind or with serious mental illness does not sit well with Mr Hunt’s claim to be a compassionate Conservative. As Ms Reeves noted in the Commons, when Richard Huntington, strategy chief of Saatchi and Saatchi, the advertising firm that helped Margaret Thatcher become prime minister, attacks the “cruel” Conservatives and forecasts a Labour election victory, then “the ravens are leaving the Tower”.

That highlights a more fundamental challenge for Mr Hunt and his colleagues. Put at its crudest: the voters have stopped listening. The assumption among many will be that by around this time next year, it will be Rachel Reeves in No 11, and whatever Mr Hunt has planned will be subject to change. After 13 years of a government, its final moves tend naturally to be overshadowed by quite vivid memories of its time in office. The return of David Cameron to the cabinet is a reminder of just how long they’ve been in power – and how many promises remain unfulfilled.

The steady stream of revelations from the Covid-19 inquiry will serve as a constant reminder of Boris Johnson’s fall from grace. There will be a similar flow of Tory backbenchers leaving the Commons and inadvertently gifting the opposition parties yet more by-election upsets. Tomorrow, the autumn statement, for whatever it was worth, will be swamped by rows over the net migration figures – likely to be up again.

Mr Hunt had a story to tell on the economy, and he did so with some eloquence, but the message doesn’t seem to be getting through.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments