It’s right to strip Philip Green of his knighthood – but removing honours involves a messy compromise

The usual line is that only conviction of a criminal offence warrants removal of any honour. Failing that you’d have to take part in a war against Britain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

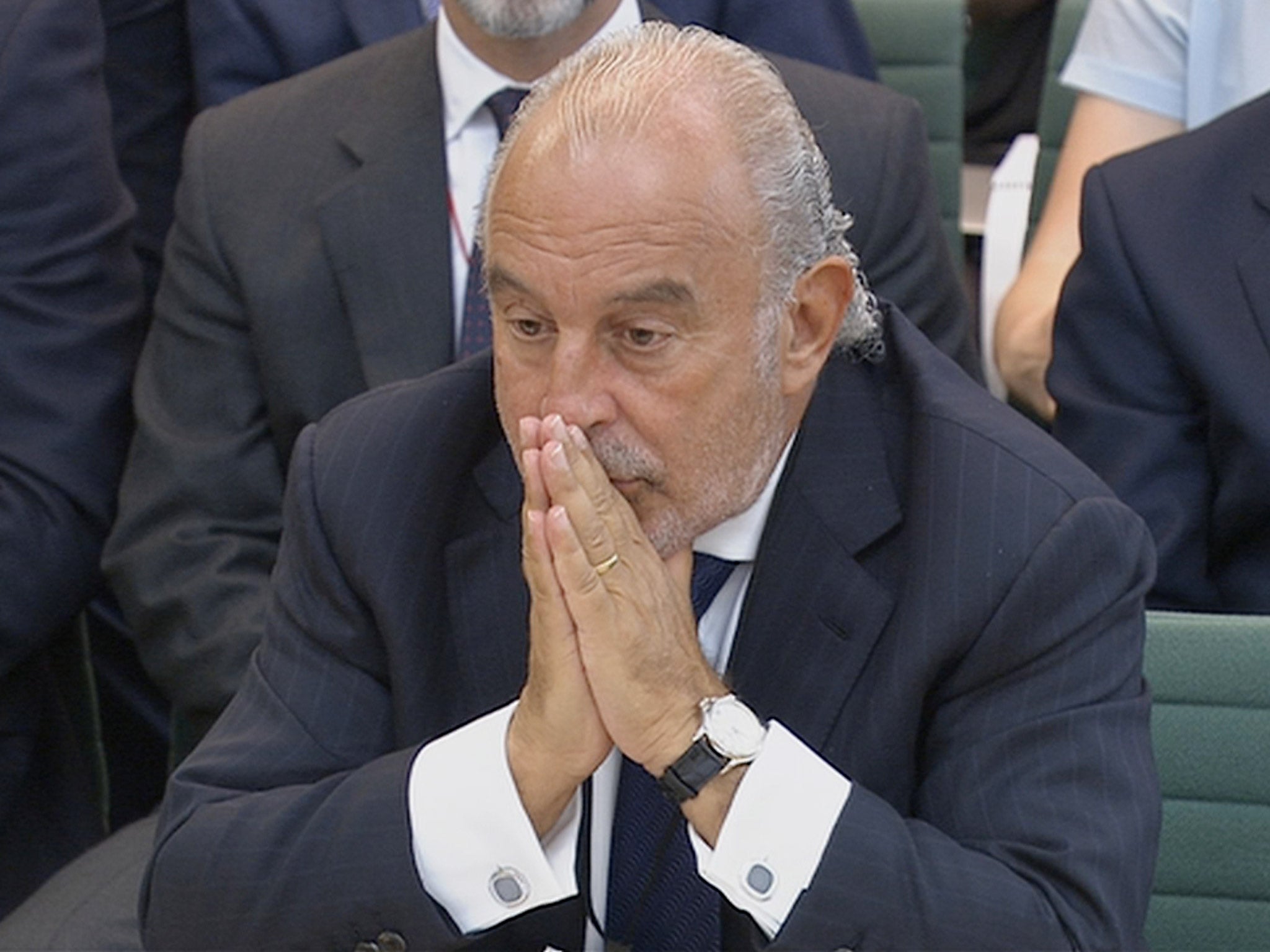

Your support makes all the difference.Few aspects of national life are so well-intentioned, and so hellish, as the honours system. Evidently, the award of a knighthood for services to business does not necessarily bestow the recipient with the universal acclaim of a grateful nation. Sir Philip Green, former owner of BHS, has had his fair share of vulgar abuse, and paid some back in the same token. Even so, the ordure heaped upon Sir Philip under parliamentary privilege has few parallels. “He took the rings from BHS’s fingers. He beat it black and blue. He starved it of food and water and put it on life support – and then he wanted credit for keeping it alive” was the verdict of Iain Wright, chair of the Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee. “Billionaire spiv” was the pithy epithet of veteran MP David Winnick. You might not expect Dennis Skinner to stint his wrath, and he didn’t: “He had the money, he had the yachts, he had the workers – and he robbed them of their pensions.”

And yet the opinions of 117 MPs – that Sir Philip should indeed be stripped of his honour – are of little consequence. Even if all 650 of them had turned up and voted unanimously to take Sir Philip’s knighthood away, it would have no force. Under a self-denying ordinance, decisions to remove honours are devolved by Parliament, or, rather by the prime minister, to the Honours Forfeiture Committee, who then make a recommendation to the Queen, who has the sole power to take an honour away. Not very 21st century, but there we are.

At the very least, there is sufficient public sentiment, not to say anger, vocally represented in Parliament, to justify Theresa May referring Sir Philip to the Honours Forfeiture Committee. The committee ought not to be too fastidious about depriving Sir Philip of his knighthood. They should get on with the embarrassing, but inevitable, task with as much haste as their dignity can bear.

A certain reluctance to do the obvious right thing about honours has, in the past, verged on the comical. The usual line is that only conviction of a criminal offence warrants removal of any honour. Failing that you’d have to take part in a war against Britain. That meant that Kaiser Wilhelm’s various honorifics were still in place in 1914, and it took a declaration of war to persuade the establishment to quietly drop Benito Mussolini from the roll call of the Order of the Bath. Sir Philip has not been convicted, or even charged, with any offence, let alone sparked a global conflagration. Yet his behaviour is bringing the honours system into disrepute and undermining public support for it more widely. That ought to be sufficient grounds, given all the circumstances. We are a democracy, after all.

Removing honours involves messy compromise. It cannot be left to MPs to determine, for that risks politicising the honours system (even more than it already is). It cannot also be impervious to the views of the public. Nor can any framework of rules deal with every possible eventuality a peer or a knight of the realm might land themselves in. Is fraud a sufficient reason to rescind an honour? If so, is the sum involved material? Is it to be determined, on a sliding scale with the seniority of the honour also taken into consideration? Should you lose an OBE but not a KCMG for drunk driving? Is possession of a dangerous dog enough to have you kicked out of the Order of the Thistle, but not the House of Lords? Is GBH necessarily incompatible with a GCB? Is possession of a joint the end of the line for a dame?

In that context the system we have now, where it is necessarily a slow and laborious process to remove an honour, is the least worst system we can devise, until we see a more thoroughgoing reform of the honours system.

New Labour once promised “people’s peers” and more senior honours distributed more widely among outstanding head teachers or doctors, say. That soon ran out of momentum, and the usual run of superannuated diplomats and permanent secretaries, not to mention newly underemployed Cameron spin doctors, reasserted itself. That is a pity.

Public servants traditionally receive honours because their remuneration is not as generous as it would be in the private sector (service in the royal household being an egregious example). For a man or woman in business to be additionally awarded some sort of public honour should mean they have also made some other outstanding contribution to national life, say through substantial work for charities or founding educational institutions. Otherwise the granting of honours to those who are merely rich doesn’t feel right, it is prone to having to be reversed when their fortunes turn down (as with the former Sir Fred Goodwin of RBS), and, as we now see, it is liable to undermine public confidence in the system.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments