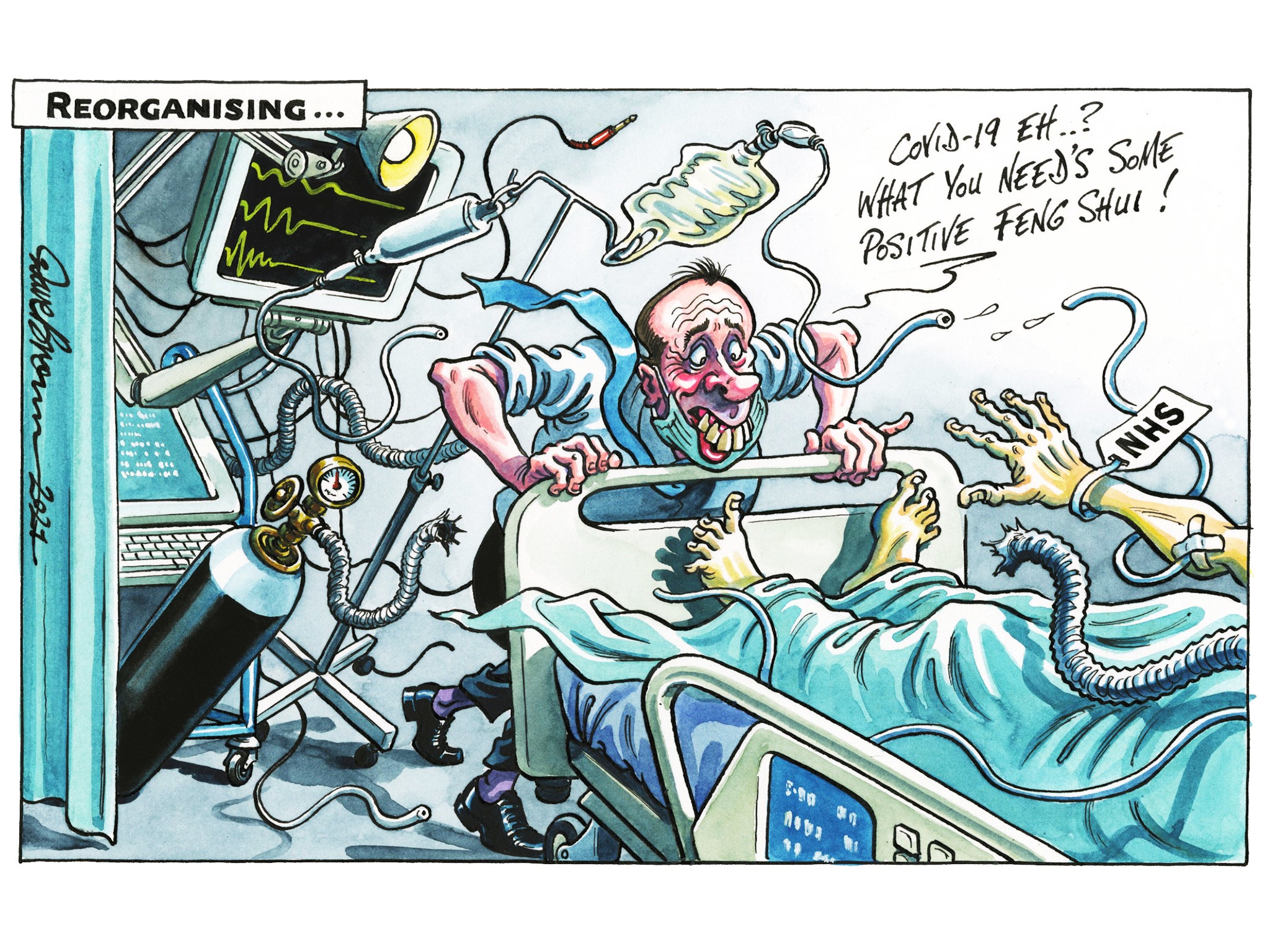

Why now? Why, in the midst of a pandemic, and with health professionals complaining that the NHS is under intense strain, is the government contemplating another wide-ranging review?

Why is this suddenly the priority when, after almost a year and £22bn expended, the nation still has no properly effective test and trace system? Or when the nation’s GPs, dentists and operating theatres will soon have to cope with a huge backlog of postponed treatments? And why, behind this sudden flurry of activity, is precisely nothing going to be done to fix the long-term crisis in social care, a full decade after the Dilnot report, which still represents the only practical set of proposals for sustainable change.

The answer given by the health and social care secretary, Matt Hancock, is “if not now, when?” The white paper on reorganisation of the health service in England (the rest of the UK is spared) is presented as the means by which the NHS will itself recover from its brush with Covid-19. It is a nice rhetorical line but the fact remains that creating complicated new integrated healthcare structures and dismantling the last lot of reforms can surely wait a little longer, until a time when clinicians, managers and civil servants don’t have rather more pressing matters to attend to.

That said, on the face of things a number of the reforms may well be beneficial, and they seem better focused than many previous waves of pointless reorganisation. The ageing population has meant more and more patients with complex needs, and they are not always well served by the current structures. Hospitals fix patients up and send them home, without having any responsibility for their care once discharged.

Local authorities struggle to cope with the increasing demands of mentally and physically infirm populations. Individuals and families have to work largely with the private sector in provision of residential care. It has to be said that redrawing organisation charts, rewriting job descriptions and creating new management structures may not be the best way to fix the lack of communication about patient care between the various agencies involved. A simple application of a statutory duty of care on all involved might go a long way to resolving the lack of coordination which is emerging as a major cause of concern.

There have been about a dozen reorganisations of the NHS since its foundation in 1948. It has been subject to almost continuous revolution, and the pace of radical change has quickened as the decades have passed. The average life of an NHS reorganisation is about 10 years, and so the scrapping of the reforms instituted by Andrew Lansley during the Cameron government is due about now. The pendulum has swung between decentralisation and centralisation, between local democratic accountability to councils and Whitehall control, between clinical staff and bureaucrats. The most clumsy and absurd was the reorganisation of 1974 which inserted an unnecessary tier of regional health authorities, in which senior executive officials were responsible to authorities which might include among their members one of their subordinates. Only a mind as brilliant as the late Sir Keith Joseph could have invented such a thing of beauty.

The public should, then, be wary of NHS reorganisations, because the link with better clinical care has so often been obscure. Very often, change is implemented in the name of efficiency, although the NHS has historically been one of the most efficient healthcare systems in the world. NHS reform is what governments that find themselves short of money do to try to disguise the underfunding of the system – looking for “efficiency savings”, notably through bogus marketisation, “internal competition”, tendering and outsourcing.

Much of that is set to be pushed back, but with no clear idea of what new financial responsibilities will take the place of the semi-autonomous NHS trusts and groups of GP practices. It may take years, again, for the new systems to bed down, perhaps with only marginal impact before the next round of reforms is due.

As the pandemic has proved, years of increasing demand from an older population, the rising cost of new drugs and treatments and a culture of financial stringency has left the system with great experience of improvisation and making the most of little, but with very little spare capacity. It is why the NHS has risen so well to the challenges that have been thrown at it, and why it never quite buckled under the strain caused by Covid-19.

It was not overwhelmed, and the nation rightly gave a clap for the carers. They worked through the crisis with inadequate equipment, through heart-rending shifts and putting their own lives on the line on the Covid wards. The one thing the heroic nurses and doctors never cried out for was a reorganisation. Why now?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments