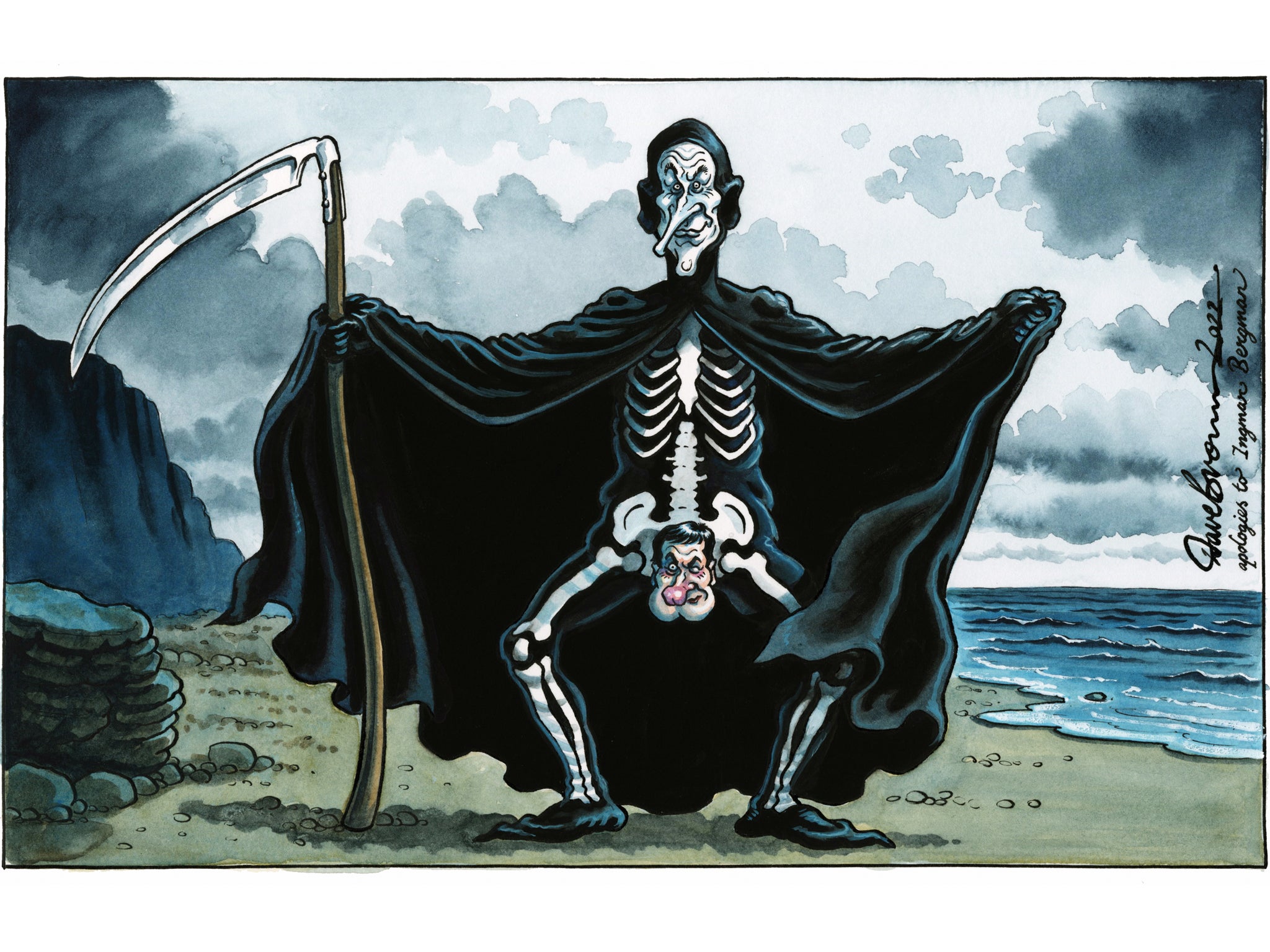

Pain now, pain later” is a reasonable summary of the chancellor’s autumn statement. Many of Jeremy Hunt’s planned cuts to public expenditure are “backloaded” (to use the jargon), kicking in towards the end of the “forecast horizon”, which – happily for the Conservatives’ prospects – happens to fall after the next general election.

However, the tax increases and some of the squeeze on the public sector will bite over the next few months. The package of support for energy prices will be scaled back after next spring. The Bank of England’s programme of steep increases to rates will add to mortgage and business costs, and – indirectly – rents.

It is a remarkable turnaround in such a short time. Less than two months ago, Kwasi Kwateng presented a mini-Budget comprising tax cuts and an energy package of £72bn, with no cuts to public spending. Now, his successor proposes a £55bn tightening – comprising around £30bn of spending cuts and £25bn in tax rises over the next five years.

Mr Kwarteng’s were the biggest tax cuts since 1972; Mr Hunt’s fiscal tightening may be the largest in modern times. The “swing” from expansion to contraction of well over £100bn in seven weeks is probably the fastest and biggest in history.

What does it mean? The outlook for households is grim, illustrated by a few key numbers from the Office for Budget Responsibility’s latest forecast. The living standards of the British people, for example, will still be lower than pre-pandemic levels at the end of 2024. Output won’t return to its level at the end of 2019 until 2027.

House prices will fall by around 9 per cent between the fourth quarter of 2022 and the third quarter of 2024, “largely driven by significantly higher mortgage rates as well as the wider economic downturn”.

Those forecasts could easily turn out to be on the optimistic side should say, global trade slow, the war in Ukraine escalates or inflation proves more persistent. On the other hand, there are a few grounds for optimism.

However harsh the next few years prove to be, the party that has governed the UK since 2010 – under a variety of guises and personalities – has to take its share of responsibility.

It is obvious that the war in Ukraine, the after-effects of the pandemic and official support policies and the trend towards protectionism across the world have all conspired to hit the global economy. Britain, so Mr Hunt informs us, is in recession, as will around a third of the world economy be over the next year or two.

Indeed, as the government points out, some European economies have been hit even harder by the energy crisis than the UK, because they were so heavily dependent on the gas pipelines from Russia.

Even so, the Conservative government that has been running the country (albeit at times in coalition or in a Commons minority) has to account for its failures in office. It’s a long list, but there are three cardinal failures.

First, was the policy of austerity that depressed investment in national infrastructure in the 2010s, notably on energy generation, security and insulation, education and the NHS.

Second, was Brexit; the effects of which have been all too well predicted and are now preventing the UK from trading its way out of its recession and into growth.

Third, was the Truss-Kwarteng mini-Budget; which appears to have imposed on the UK an entirely unwished “moron premium” on its cost of borrowing, a lasting and expensive legacy from that brief experiment with radical supply-side reform and unfunded tax cuts.

The net result of a dozen years of Tory rule is lower trend rates of growth than in many decades. Given how paltry growth rates have been since 2007, it’s fair to say the UK has been close to (or in) recession ever since.

The last two decades, since the global financial crisis, have been dismal for the British people. The notion that Brexit would revolutionise the situation has been a cruel deception. Despite Mr Hunt’s latest plan for growth, the 2020s look set to be another decade of stagnation.

As polls and economic forecasts stand, it looks very much like it will be the next government – probably a Labour government – that will have the worst of the task of fixing the mess in the public finances, and trying to generate some sort of economic growth and a boost to living standards.

To keep up to speed with all the latest opinions and comment sign up to our free weekly Voices Dispatches newsletter by clicking here

Politically, it is difficult for Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves to be too explicit about how much Brexit is continuing to stymie economic growth, still less promising to reverse it (which would be by far the best plan for growth).

But Brexit will have to be revisited. Is it too much to hope that Brexit will at least be reformed by the time the 2030s arrive and another decade gets lost to economic delusion? Whatever the theory of Brexit, or what “the Brexit people voted for” was, the actual experience of Brexit hasn’t felt as liberating as once promised.

Britain has not “prospered mightily” as Boris Johnson said it had. If it had been true, the UK would not now be struggling to pay for its public services. Public opinion is certainly moving in the direction of Brexit reform. A few more months of recession may concentrate a few more minds in that direction.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments