The Government is right: the time for a second Leveson inquiry has passed

While not immune to criticism, the free media – print and digital – has in recent times championed the principles of human rights and made them real for many people.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The new Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, Matt Hancock, has moved swiftly to end the uncertainty surrounding potential future investigations into the press by cancelling the so-called Leveson 2 inquiry.

While some will be disappointed by the decision, at a time when a free press is needed more than ever, he was ultimately right to excise this intrusion and distraction. He has drawn a line that needed to be drawn, even though Lord Justice Leveson himself might disagree.

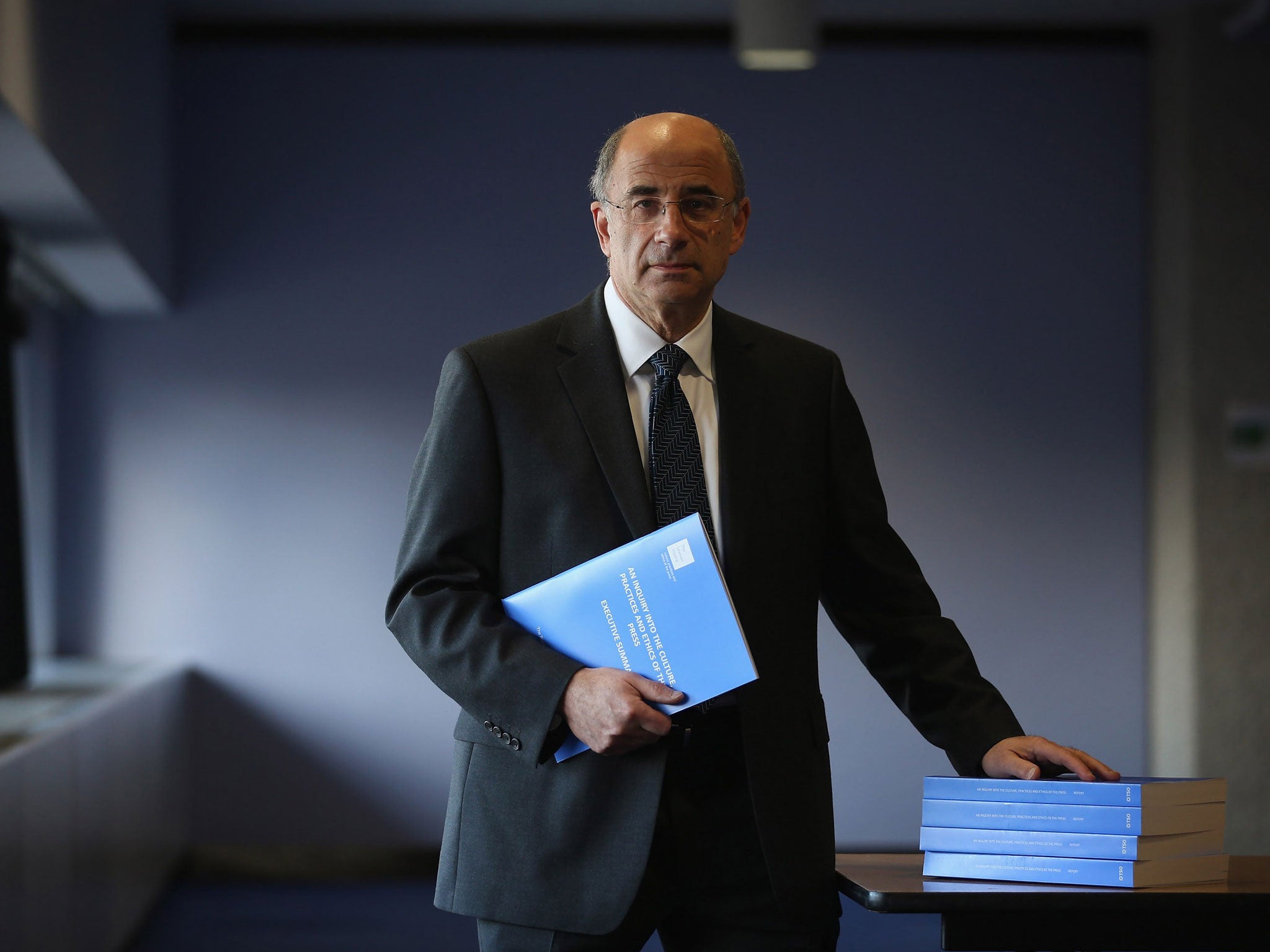

It was to have been the second part of a judicial investigation into the culture and practices of the British press, initiated in 2011 by David Cameron in response to the phone hacking scandal and amid broader concern about persistent abuses by some journalists and news organisations. Apart from the usual business of character assassination and straightforward political propaganda – all’s fair there in love and war – some journalists had invaded privacy, intruded on grief, impeded police investigations, acquired information illicitly and generally trashed other people’s lives in the pursuit of a story.

In a few places malpractice was endemic; in many others it was virtually unknown. Rupert Murdoch’s News of the World, which became a totem for all that had gone so very wrong, was forced into closure.

The first Leveson Inquiry heard a great deal of damning evidence and there followed some high-profile prosecutions and resignations. We cannot doubt that important light was shone into some pretty dark places.

While it may be going too far to think that journalists acting badly have been entirely eliminated from every newsroom, the British media demonstrably responded positively to the Leveson Report and to the changing public mood.

That closure of the UK’s leading Sunday tabloid, as well as the jailing of Andy Coulson, its former editor and one-time aide to Mr Cameron, and the instigation of a fresh, if not flawless, self-regulatory apparatus in the form of the Independent Press Standards Organisation have all demonstrated how times have changed.

If the media remains occasionally imperfect, it is not unreasonable to wonder whether it could ever be otherwise, given that the business is so much about the frailties of humanity. News publishers are also right to point to the work journalists continue to do in exposing hypocrisy, criminal activity and the abuse of human rights in every part of the world.

From breaking the silence about child-grooming gangs, to the latest stories about sexual abuse by aid charities and in show business; from exposing the truth about the Trump election campaign’s links to Russia, to reporting on the horror of terrorism and war in Syria, Yemen and elsewhere, it is the free media, print and digital, that has championed the principles of human rights and made them real for so many people.

Good, outstanding work continues to be done day in, day out, by conscientious reporters, video journalists, commentators and editors. In local courtrooms and council chambers as well as in the UN and Brussels we need people to tell us the stories straight. As things stand, that culture of public transparency is being eroded, and not by and large by working journalists: that is a much more pressing issue, in all honesty, than examining the past.

The truth – and journalists are in the main in a truthful trade – is that the second leg of the Leveson Inquiry had become outdated. Partly that is down to a change in ethics and behaviour that has already occurred; but also because it was to be essentially backward-looking and, as with the first inquiry, eccentrically confined, for the most part, to traditional print-led organisations rather than paying heed to the explosion in online journalism and the use and misuse of social media.

This decision and the Government’s promised review of “fake news” at least suggest it understands that the landscape has changed. It is welcome too that Hancock has reiterated ministers’ desire to abolish Section 40 of the Crime and Courts Act. This pernicious piece of legislation, while not yet enacted, has sat menacingly on the statute book and promised huge legal costs to any news publishers which refused to sign up to royal charter-approved regulation.

At a time when journalism has never faced a more challenging commercial future, politicians should be thinking creatively of how to help the industry, not hinder it. They should remember that during upcoming debates over the Data Protection Bill.

The media, in all its many and varied forms, should not be immune to criticism – or from the responsibility that is the natural partner of freedom. What’s more, there is much still to be done to make the media, to borrow a phrase, work for everyone. But another £5m judge-led inquiry wasn’t going to make anyone (aside from the lawyers) better off.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments