Four nations, three tiers, two front benches at war, and one micro-virus stubbornly resisting attempts to suppress it: Britain’s struggle against Covid-19 is becoming an increasingly divided and divisive affair. It is not a promising way to be entering the first Covid-era winter.

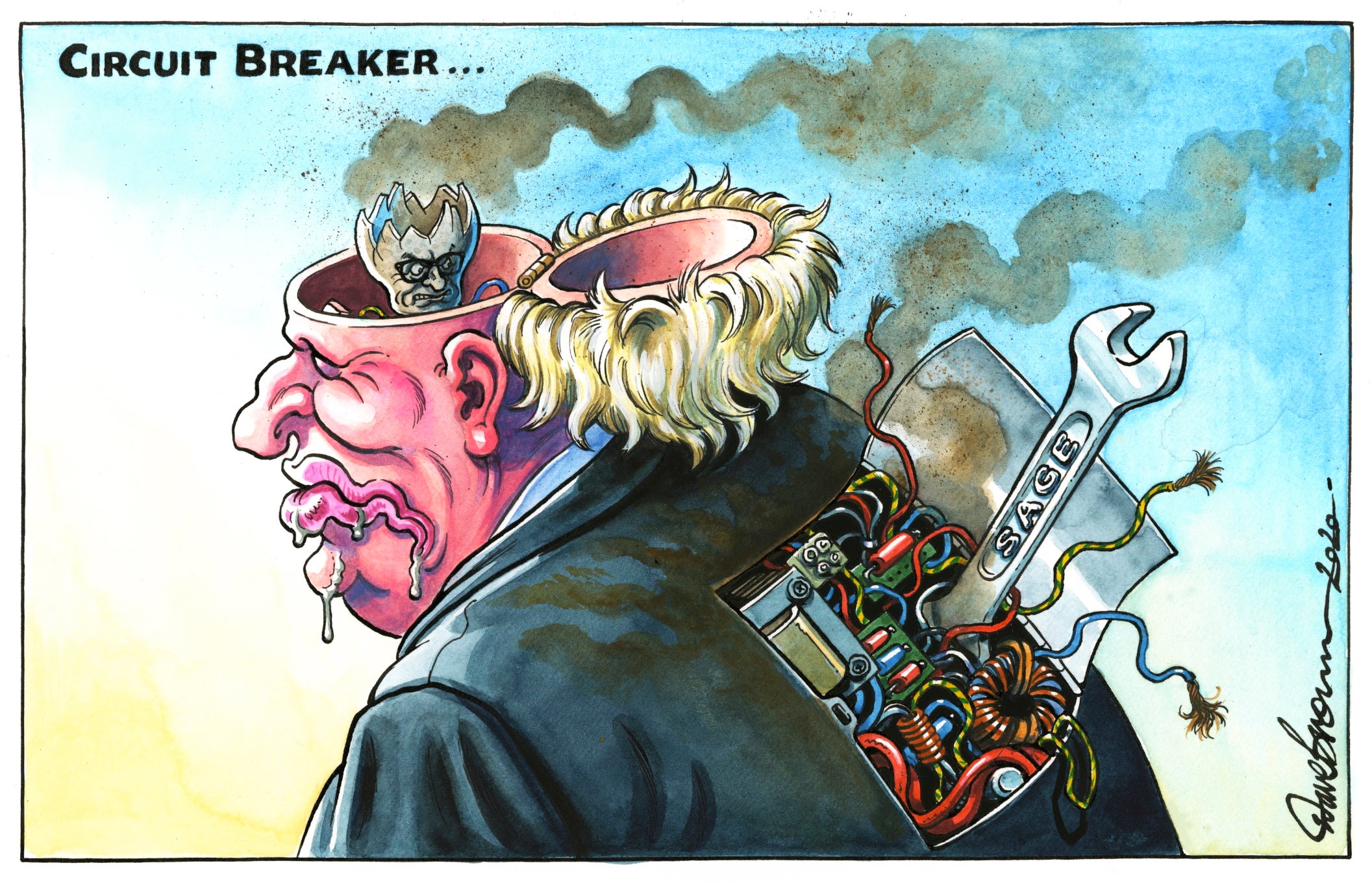

A short national lockdown now seems inevitable, despite the prime minister’s increasingly desperate efforts to avoid it. His scientific advisers have strongly advocated it, the opposition is demanding it, and more and more parts of the UK are moving into increasingly stringent restrictions on social freedoms and business activity.

Northern Ireland, Wales and Liverpool have now joined much of Scotland and moved into near-total lockdown. The government of Wales is proposing to ban thirsty visitors from high-risk areas such as Liverpool, the first restriction on free movement of people between England and the principality since 1536. Soon Greater Manchester and parts of the Midlands may join Liverpool City Region in tier three. Greater London may in the coming days be nudged into tier two, as its mayor, Sadiq Khan, predicts. Many millions already live in tier-two areas, where they enjoy more freedom but with the added disadvantage that their hospitality businesses won’t qualify for special financial assistance from the state.

Some local and regional leaders back the government; others do not, broadly but not consistently, on party lines. Mayors such as Greater Manchester’s Andy Burnham claim they are treated with contempt by ministers, a complaint long heard from Nicola Sturgeon and Mark Drakeford. Division, argument and fear is everywhere, and hope for a successful test and trace system correspondingly scarce.

Within weeks if not days, then, the majority of the UK population will be living under something close to the first lockdown conditions in the spring, especially with the schools closed for half term. At some point, the government’s “regional approach” will cover so much of the country that the relatively loose “medium” tier one conditions will prevail in the more remote districts of Cornwall. The step from de facto to a formal national lockdown will be a relatively small one. Even so, it is likely to be opposed, as are many of the current restrictions by a substantial body of Conservative MPs, who have already staged a symbolic Commons rebellion on the 10pm curfew.

The good news for Mr Johnson is that he need not pay much attention to them because he can rely on overwhelming support from Labour, the SNP and the other opposition parties. The bad news is identical – a government with a nominal working majority of 87 cannot get its policy through parliament without Labour’s help.

His party and his cabinet are badly divided on Covid, with resignations perhaps not far away for some. There is an eerie echo here of parliamentary shenanigans during the Brexit debates last year. Even when faced with a pandemic, Britain’s political system seems incapable of producing strong and stable government. It is difficult to see how a no-deal Brexit at the turn of the year will make things any better. Mr Johnson’s troubles will only intensify.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments