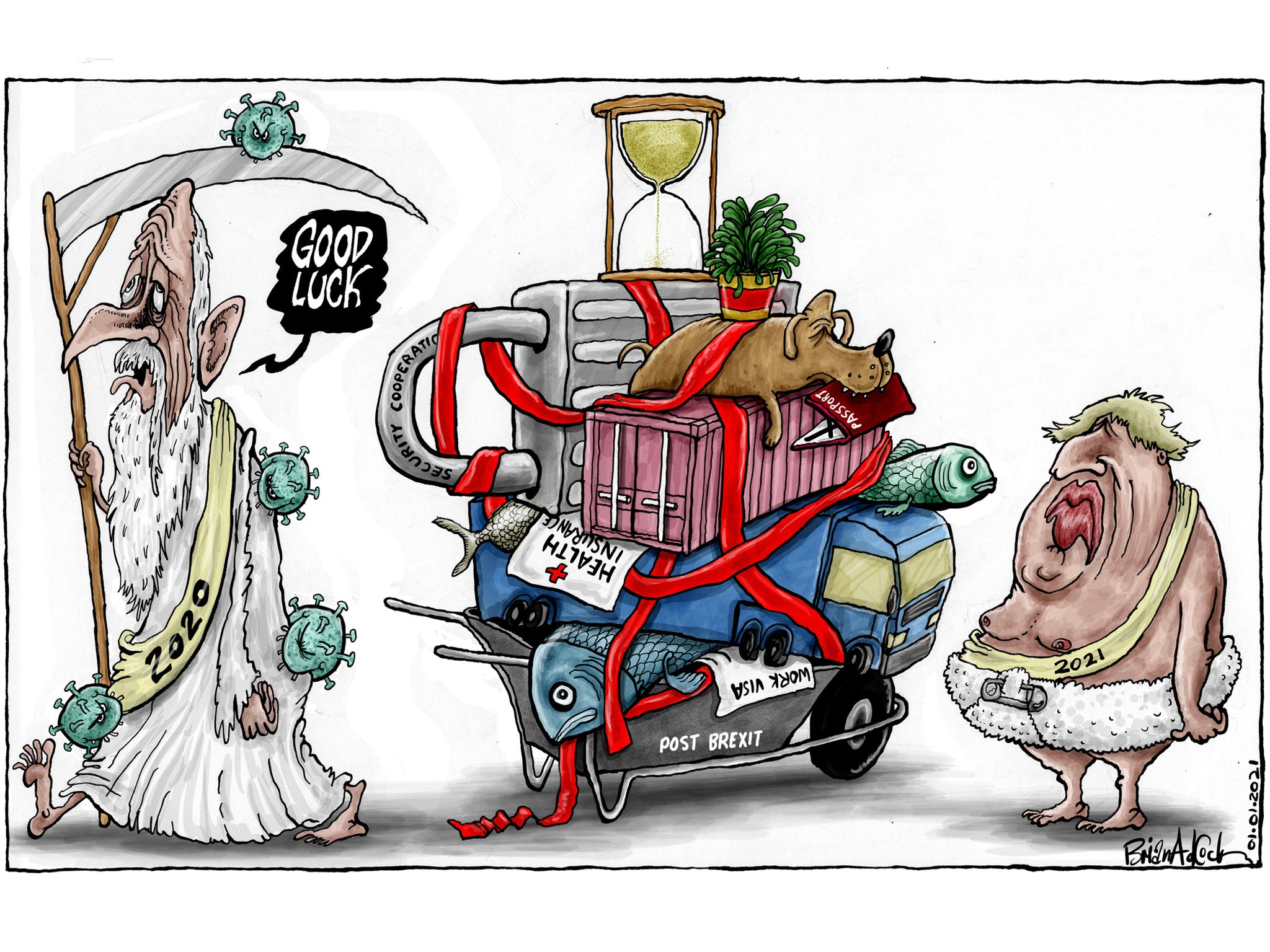

It is a truism that has been expressed in this space many times that there is nothing final about this change in our relationship with the European Union. That relationship will be renegotiated constantly for as long as we continue to interact with our neighbours.

Yet it is also true that this is a significant historical moment. It is the point at which our membership of the EU ceases in practice, 11 months after it ceased in law. For almost the last year we have been treated as if we were still a member state; now we will be treated differently.

For nearly half a century, the United Kingdom has helped shape the European project, and has been shaped by it, mostly for the better. The creation of the single European market and the expansion of the EU to encompass most of central Europe were geopolitical changes of great moment, in which the UK played a leading part.

The long period of UK prosperity, from 1992 until the financial crash in 2008, was made possible by the single market and was boosted by the free movement of workers, especially from central Europe.

When The Independent was founded in 1986, it was sceptically pro-European in the original sense of the word, before it was coopted by opponents of closer integration. That view has been one of the fixed points of The Independent’s existence. At the time of our launch, the parties were undergoing the “great switchover”. Labour under Neil Kinnock had renounced its policy of withdrawal from the European Community (without a referendum, incidentally), a shift sealed by the address given to the Trades Union Congress in 1988 by Jacques Delors, the president of the European Commission.

The opposite shift of the Conservative Party was marked by Margaret Thatcher’s speech in Bruges that year, a reply to Mr Delors, in which she said, quite moderately, that the European family of nations should be “doing more together but relishing our national identity no less than our common European endeavour”.

At the time, the debate was about the nature of that common endeavour, and it was conducted entirely on the assumption that Britain would be part of it. As Mrs Thatcher said: “Britain does not dream of some cosy, isolated existence on the fringes of the European Community. Our destiny is in Europe, as part of the community.”

But the language of the “Eurosceptics” became less moderate, and the debate about the single European currency gradually became a proxy for a deeper argument about EU membership itself.

While the parties realigned themselves, The Independent remained true to its founding values, arguing for reform of the EU, worrying about the distance of its institutions from the peoples for whom they were supposed to be working, and in favour of a more complete single market. We feared that David Cameron’s attempt to renegotiate the terms of the UK’s membership was as cosmetic as Harold Wilson’s had been 40 years earlier, but less likely to be successful – and, crucially, would fail to repair the real weaknesses of the EU polity.

When it came to the breach, in the 2016 referendum, by a narrow but decisive margin, it seemed that the most democratic interpretation of that decision would have been a close relationship from outside the EU, such as that enjoyed by Norway or Switzerland. However, the internal politics of the Tories, and the unavoidably adversarial nature of the House of Commons, drove Boris Johnson, the leader of the Leave campaign, towards a more extreme version of Brexit.

That was why The Independent thought it right to give the British people a chance to think again; but it was an unconvincing proposition for Jeremy Corbyn, who did not believe in it, to sell in a general election.

However, our fundamental position has not changed. A close relationship between all the nations of Europe is in all our interests. A reformed EU is the best expression of that unity – although it needs democratic reform more urgently than ever, as the cases of Hungary and Poland confirm.

Hamish McRae, our economics commentator, once said that he thought the UK would move from being half in the EU to being half out, and that is probably how it has to be. In the long view, the UK cannot escape what Mr Johnson calls the “gravitational pull” of the continental economy, and it would be damaging to try to do so.

Seen in historical perspective, Britain will always be a close partner of the EU, whatever shape it takes. In The Independent’s view, our departure from both the political and economic structures of the EU was an overcorrection, although it is only now that we will discover how much it will cost; and we will spend most of the next decade negotiating a closer and more productive relationship.

The UK ought to be part of what Mrs Thatcher called “our common European endeavour”, and the closer we are to the institutions of that endeavour, the better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments