Ursula von der Leyen, president of the European Commission, was graceful and thoughtful in quoting Shakespeare as Britain’s membership of the European project came to its practical end. “Parting is such sweet sorrow,” she said.

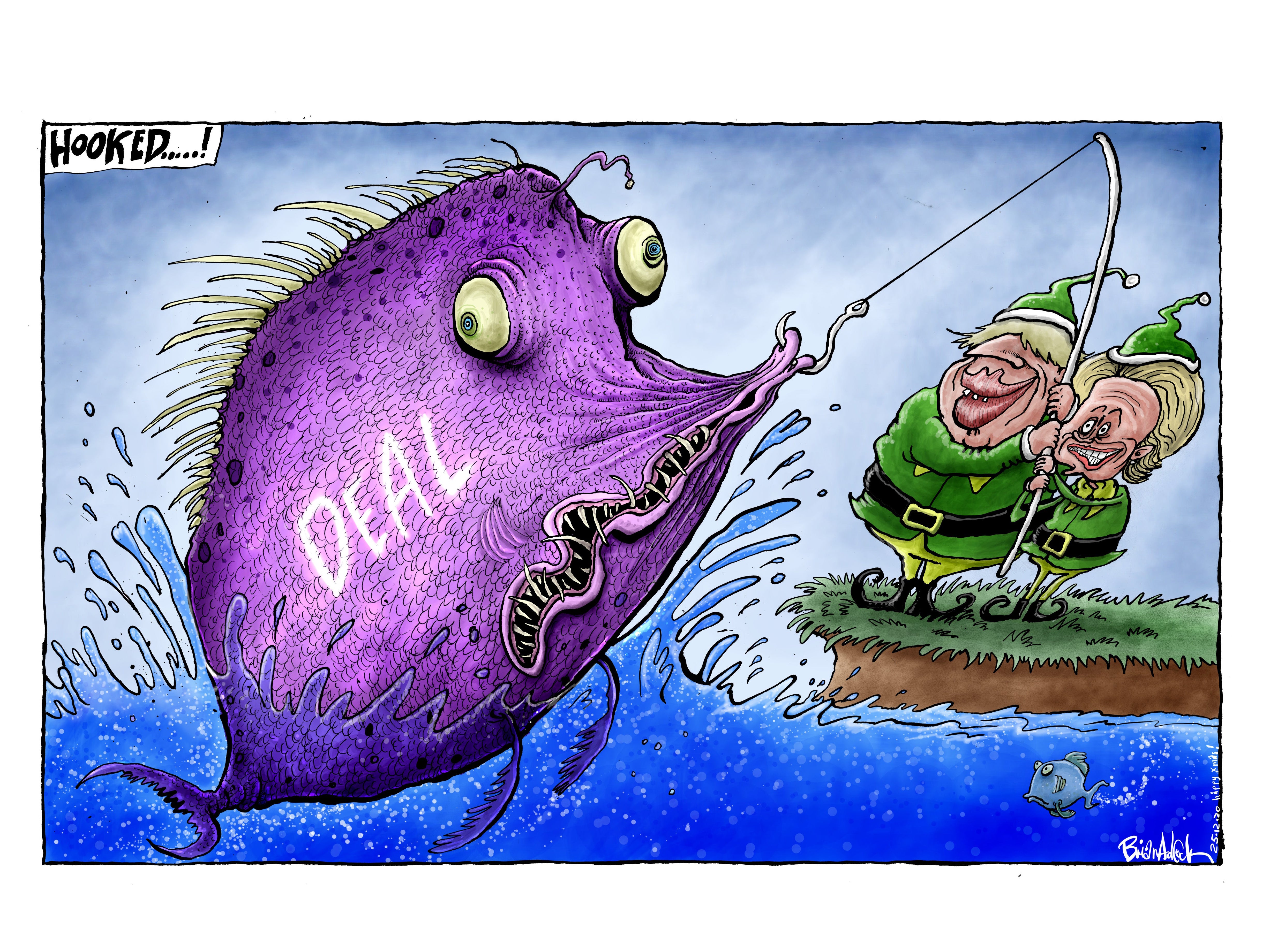

The German politician looked and sounded sad, as did Michel Barnier, the EU’s masterful chief negotiator. Boris Johnson, by contrast, tweeted an image of himself with his arms in the air as if England had just won the World Cup. That is not how a good half of his fellow citizens, if not more, feel about this unwelcome Christmas present.

The relief that a deal has at last arrived should not disguise this moment of national self-harm. As Mr Barnier reminded us, the sadness for Britain and for the rest of Europe is to compare what lies in front of us with the unlimited freedoms to work, study and trade that existed for most of the past half-century.

The prime minister did what he always does: oversold his deal. He joked that it was not his intention to portray the deal as a “cake-ist treaty”, but that is precisely what he is attempting. The conceit is to pretend that goods and, more importantly, services can flow just about as freely in future as they have in the past. This will not be the case, and companies large and small, as well as many individuals, will shortly discover the unpleasant but timeless truth that you cannot have your cake and eat it.

Contrary to what Mr Johnson claims, there will be many non-tariff barriers to trade and “behind the border” obstacles to UK firms winning new business in Europe. Every product, foodstuff, professional service and anything else will have to be acceptable to the EU. In particular, these will be subject to what Barnier called “unilateral” sanctions.

The further the UK diverges from single market rules, either through the choices of individual businesses or by laws passed in Westminster, the less access there will be to the largest single market in the world. That is as true as it was when Theresa May was struggling with the concept of “dynamic alignment”; it has been loosened and rebranded, and the European Court of Justice taken out of the framework, but the practical effect is more or less the same.

It would certainly be a surprise if, having left the EU single market and customs union, British businesses were able to export more to Europe.

To add to the damage to investment, employment and growth of historic proportions, the loss of the Erasmus scheme and real-time access to EU databases are just two of the most painful losses, and once again a self-imposed injury on the part of London. The true scale of how far and how quickly the UK will become poorer and less secure will become apparent in the coming days, as the 2,000 pages of text become available, scrutinised and analysed.

It is better than nothing, this deal, and it will pass through parliament rapidly with the expected support of Labour, though the SNP will probably make a symbolic show of resistance, safe in the knowledge that “no deal” has been avoided.

What this flimsy new treaty will not do is end the national argument about where Britain’s prosperity and security lies. The sensation of relief is very real and welcome, but only in the way it is when you stop banging your head against a wall.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments