It would be no bad thing if the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill were delayed so that the issue could be considered further. Normally, this might seem like an attempt to avoid a difficult decision but assisted dying is a special case. Legalising it would be a fundamental change and is fraught with the possibility – indeed the certainty – of unintended consequences.

Although the issue has been debated by those with a personal or professional interest in it for decades, many of the cohort of MPs who will vote on Friday have been legislators for only four months. The text of the bill was published only three weeks ago.

Given the complexity of the subject – and given that so many people appear to be changing their minds when they learn more about it – MPs are entitled to feel that they are being rushed into a decision.

The bill’s promoters – and the government – insist it will have enough time during its passage through parliament for doubts about how the legislation will work in practice to be assuaged. There are questions, for example, about how the overloaded court system will deal with approvals for assisted deaths, not to mention how the overloaded National Health Service will be able to deal with such a change in the assumptions underlying end-of-life care.

However, if the bill secures its second reading on Friday, it will gain a momentum of its own. It would still be possible for MPs to vote against it later on, after it has undergone line-by-line scrutiny and amendment. The House of Lords may take a different view from that of the Commons – and would be within its rights to do so, given that the proposal was not a manifesto promise.

But those MPs who are hesitating about setting the wheels of legislation in motion are justified in doing so. They should not be accused of being indecisive. Indeed, we should be suspicious of those people – on both sides of this debate – who are certain they are right. Assisted dying is one of those issues on which the courageous position is to embrace uncertainty.

That is why so much of the debate is about “safeguards”. If it were straightforward to give adults of sound mind a lawful choice about painful and terminal illness, the law would have been changed long ago. But such a change risks being abused, and can have consequences not foreseen by the legislators. The Canadian parliament, for example, thought it had hedged its law with safeguards, and most of its MPs did not intend to allow the cases that have occurred of people feeling under pressure to end their lives to stop being “a burden”.

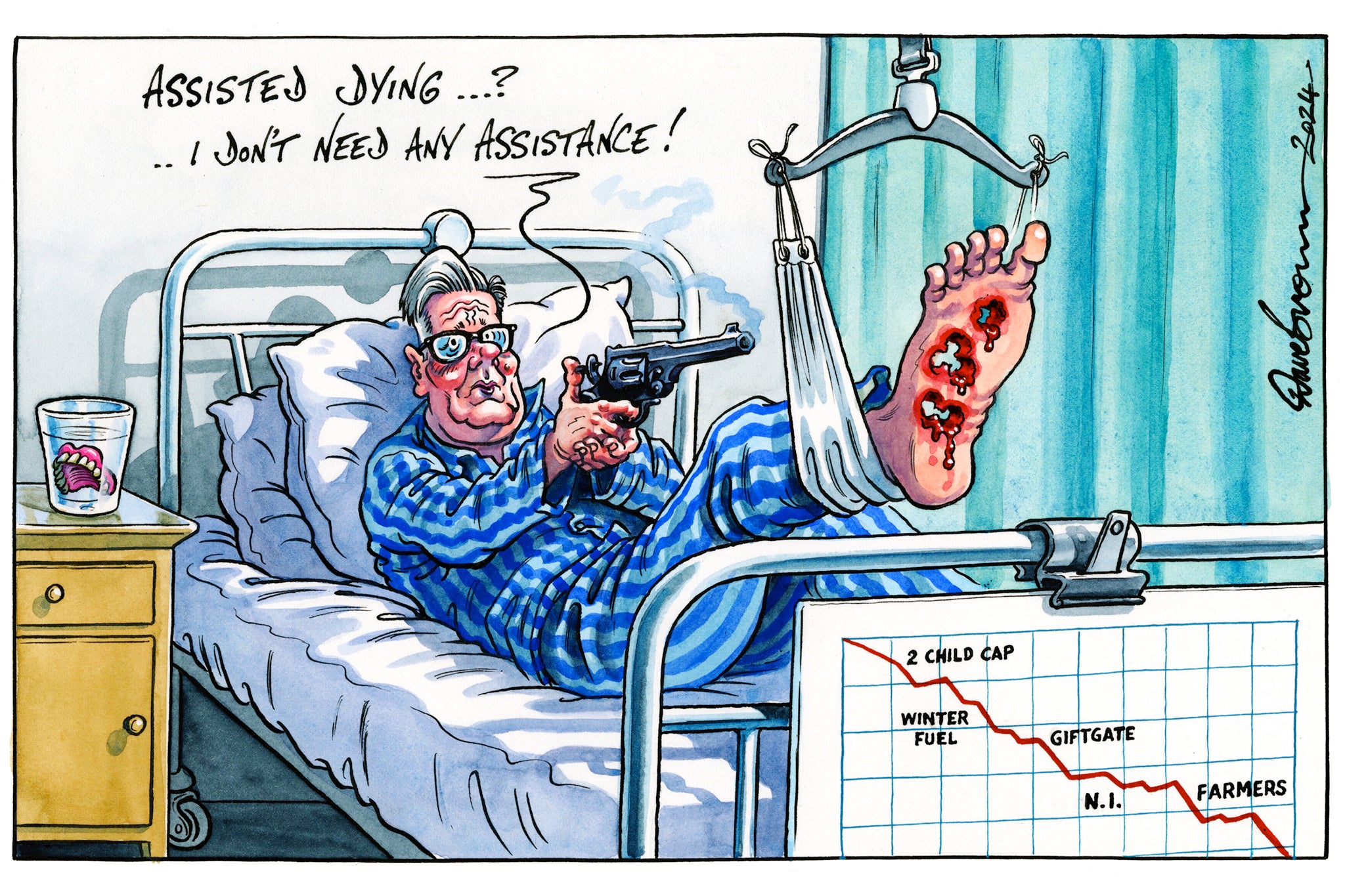

It may be that Britain is ready for assisted dying – and that it should be the next big change in social liberalism. But, if so, it is critically important to get the legislation right – and it may be that the House of Commons is not yet ready.

As Gordon Brown said in his wise intervention last week, “sometimes” Britain “can move too fast on an issue where it should go slower, listen and learn”. He suggested that “with the NHS still at its lowest ebb, this is not the right time to make such a profound decision”. He called for a commission to draw up a 10-year plan to improve end-of-life care.

The Independent is not in the habit of calling for commissions, reviews or consultations, which are usually a way of deciding against something by deferring a decision. But assisted dying is different – and a decision to legalise it would be easier if end-of-life care were better. There is an argument for improving palliative care first and then considering a bill such as the current one.

Whatever the result of Friday’s vote – but especially if it is close – MPs should take their time over this legislation and let us improve end-of-life care in the meantime.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments