The authority that investigates miscarriages of justice has serious questions to answer

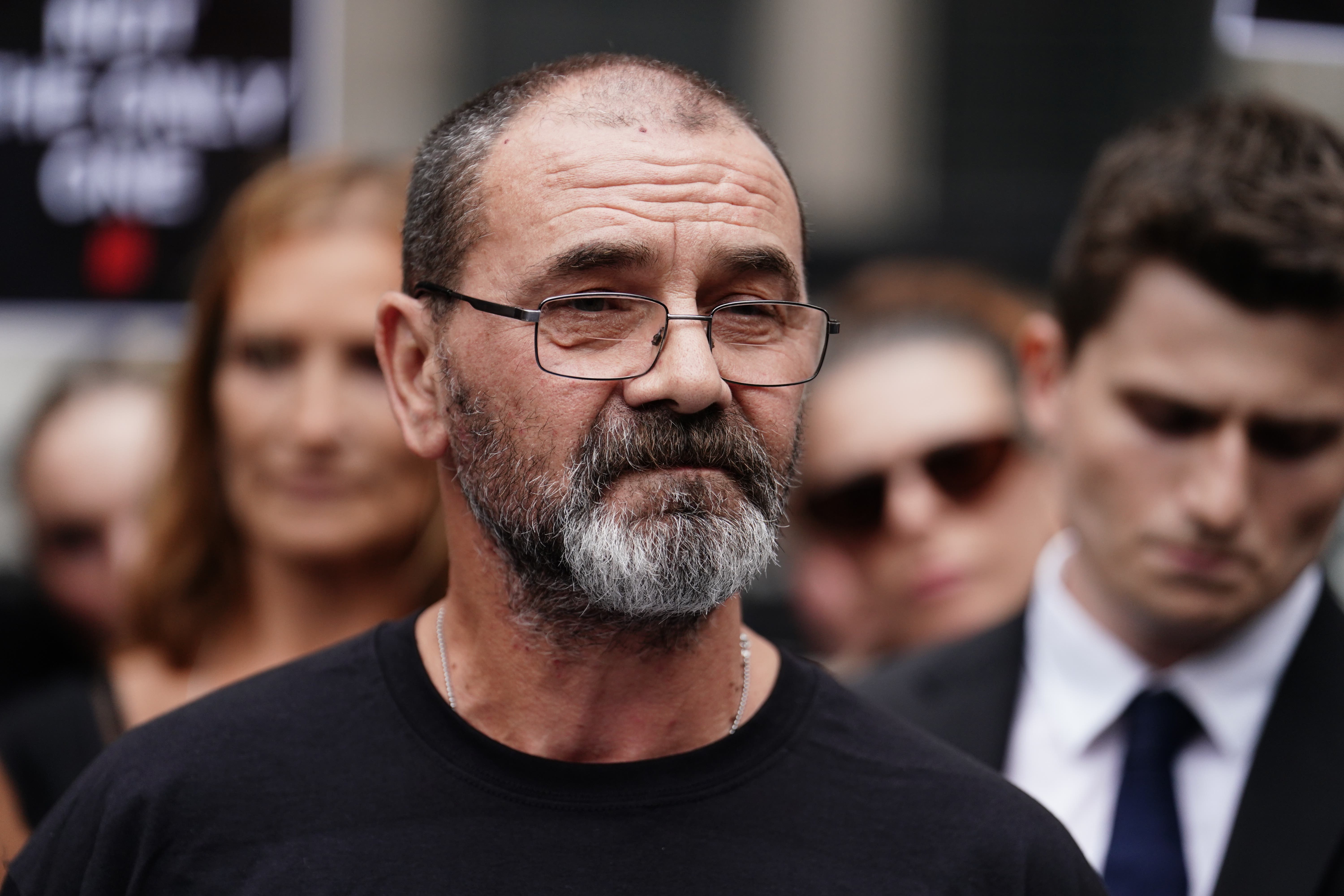

Editorial: Andrew Malkinson spent 17 years in jail for a rape he didn’t commit. So why did the Criminal Cases Review Commission take so long to clear him – when they had the evidence that would prove his innocence?

Any journalist who has tried to report a miscarriage of justice case knows how difficult they can be. Until the accused has been formally exonerated by a court, there are always doubts about the evidence. Our prisons are full of criminals volubly and sometimes convincingly protesting their innocence.

So we do not pretend that the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) has an easy task. Yet in the case of Andrew Malkinson, the man who served 17 years for a rape he did not commit, it ran out of excuses for its failings long ago.

As Nazir Afzal writes for The Independent in a powerful article today, the case against Mr Malkinson had fallen apart in 2007, and yet he spent another 13 years in prison after that. Mr Afzal, the former chief crown prosecutor for North West England, writes that this wrongful conviction “has been uncovered in spite of the mechanisms set up to carry out this task, not because of them”.

The Greater Manchester Police, the Crown Prosecution Service and the CCRC all refused to consider the possibility that the wrong man had been jailed, despite a cold case review that produced DNA evidence putting another man at the scene of the crime.

These cases may be difficult, but it was not that difficult at this point, four years after Mr Malkinson’s conviction, to see that there was a serious risk that a grave injustice had been done. The CCRC dismissed his request for further DNA testing – which eventually cleared his name – commenting internally that “further work would be extremely costly”.

This does not seem plausible. No doubt budget cuts were a problem for the organisation, but it would seem that a more important issue in this case was a strong institutional reluctance to question the jury’s verdict on an emotive crime.

It would seem that the CCRC has fallen victim to the wrong mindset. It was set up in 1997 to change the idea that the criminal justice system never made mistakes after the release of the Guildford Four in 1989 and the Birmingham Six, cleared in 1991. They had been convicted in the 1970s at a time of anti-Irish prejudice, and when deference to the police and the legal establishment was strong.

It is unimaginable that those kinds of miscarriage of justice could happen again, for which we should be grateful. Yet the CCRC seems prone to other faults, just as serious: to bureaucratic inertia, to the belief that “it is all too difficult” (for which the excuse is “too expensive”) to investigate even clear cases of concern.

It was not “too difficult” for Bob Woffinden, a dedicated journalist, to realise that Mr Malkinson’s conviction was unsafe. It was not “too difficult” for a tiny and under-resourced charity, Appeal, to pursue Mr Woffinden’s concerns.

And yet, even now, after the CCRC has announced an inquiry into its own processes, it has failed to issue an apology and we have not even heard from Helen Pitcher, its chair. This is a woeful abdication of leadership from an organisation urgently in need of renewal.

As Mr Afzal argues in our pages, the truly frightening thing about Mr Malkinson’s case is that he was lucky. He was lucky that the case against him was so flawed; he was lucky that his lawyers persisted on his behalf; that his case was picked up by a campaigning journalist and caught the eye of the leader of a legal charity.

At every step of the way, Mr Malkinson was obstructed by the police, the CPS and the CCRC. When they should have leapt at the chance to be sure that they had got it right, they blocked and tried to shut down any suggestion that they had got it wrong. No shortage of funding can excuse such a fundamentally mistaken attitude.

All three organisations should ask themselves searching questions, and the CCRC in particular needs to rethink its mission from the bottom up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments