Afghan refugees deserve better than to be forced into homelessness

Editorial: The air force pilot we have singled out stands for thousands of other Afghans who endangered their lives when they served the British, and deserve far better treatment than they are currently receiving

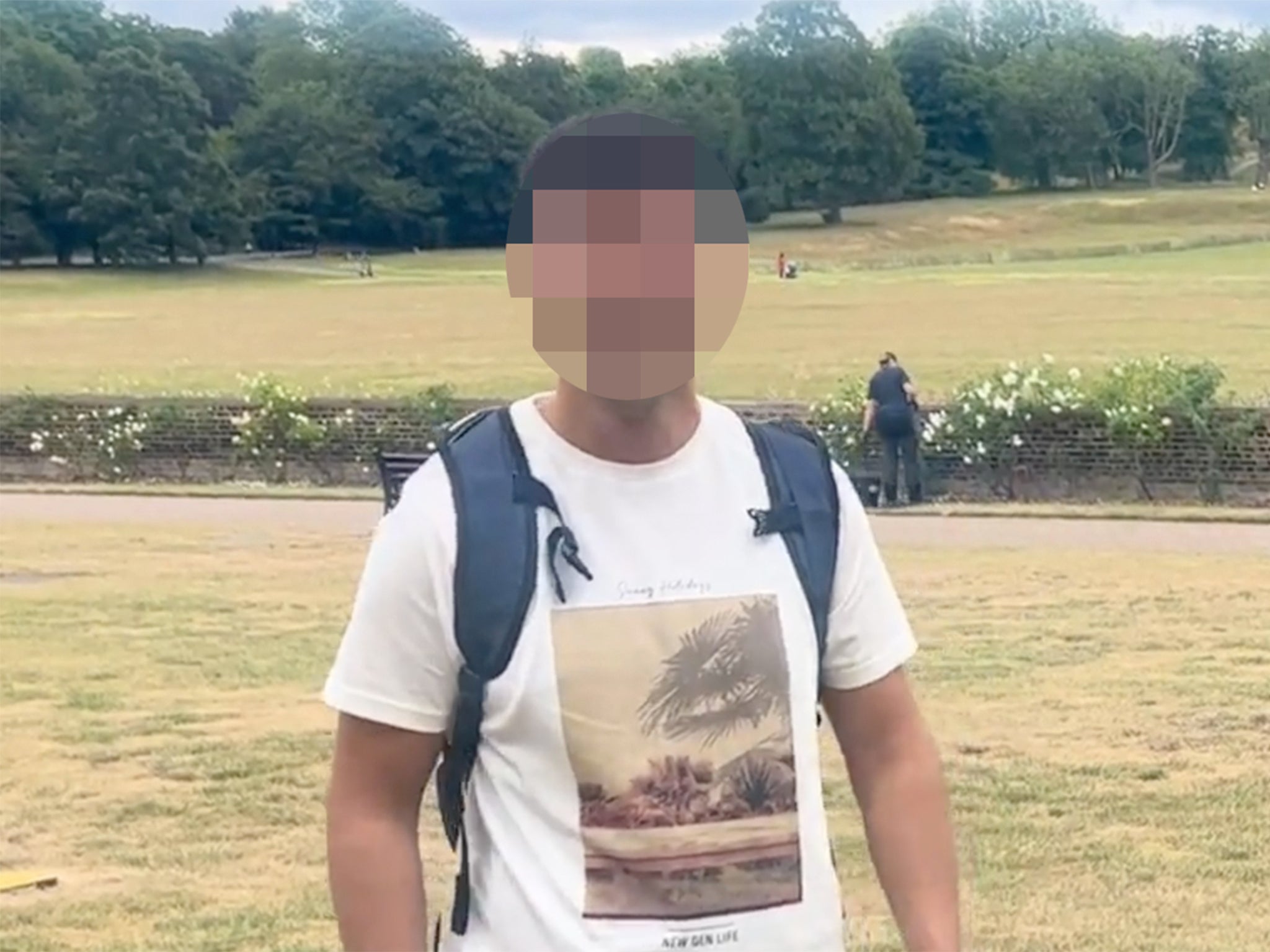

As so scandalously often happens, it takes distressing revelations about the plight of one individual to highlight far wider policy failings. But it beggars belief that the individual whose difficulties we report today is the very same Afghan pilot whose perilous quest to reach safety in the UK has already been charted by The Independent.

It turns out that the air force lieutenant, who arrived by small boat after inexplicably failing to qualify for the Afghan resettlement scheme (Arap), is among thousands of new refugees now facing eviction and potential homelessness, in part because of a government rule change. Where successful asylum seekers used to be given 28 days to leave their Home Office-paid accommodation, the starting point for those 28 days has now changed, leaving some with as little as a week to make alternative arrangements.

The effect is that what should be a time of joy and immense relief – the day someone learns that their asylum claim has been granted – turns sour almost at once. The success of their claim means that they must now find their own housing. So, the good news for the Afghan pilot is that he may stay in the UK, but the bad news is that he faces imminent eviction from his Home Office hotel and must find somewhere else to live.

The deficiencies of the UK housing market are legion. What with the acute shortage of social housing, the lack of decent and affordable private rentals in many areas, and the upfront costs associated with a new tenancy, finding somewhere suitable to live is hard for anyone to navigate. For relatively new arrivals who have had their housing – however unsatisfactory it might be – provided by the Home Office for many months, even for years, the task is many times more difficult.

Almost the only recourse they have is to the local council, which is no doubt why more than 13,000 refugees with recently granted asylum status have applied to their councils for emergency housing help so far this year. This is a big increase on last year, when more than 8,000 people in this position approached their local council.

Perversely, one reason why this situation has worsened so dramatically would appear to be the result of what would otherwise be a positive development: the Home Office is finally speeding up the processing of asylum applications. As more acceptances emerge from the system, so more successful asylum seekers must look for accommodation. Not only is this another instance of central government passing the buck to local councils, but it also comes at a particularly bad time for councils, some of which already face bankruptcy and many of which are overstretched, especially on the provision of housing.

Once again, we see both a lack of coordination between central and local government and a total absence of joined-up thinking in the asylum system generally. No one seems to have anticipated, still less catered for, the pressure that faster processing of asylum seekers would put on local councils. This is then exacerbated by eviction notices that come into force sooner than before.

One of those affected is the former Afghan air force pilot, who The Independent has been following. As he reasonably points out, if he gets a job, where will he sleep? And without an address, how can he find a job?

This, of course, is the catch-22 faced by many homeless people in the UK, not only refugees. But it is absurd that those whose asylum applications are successful, then face such difficulties. The reward for success is to go from being completely protected by the state one day to losing all their protections the next.

The one concession made so far seems almost to add insult to injury. After pleas by MPs, the Home Office has agreed to halt evictions between 23 December and 2 January – a time when there would doubtless be few around to enforce them anyway. This is no way to treat those who have not only sought sanctuary here but who have had their claims recognised as valid.

After the desperate situation of some “Triples” – members of special forces units who had served in highly sensitive roles, but denied access to the Arap scheme – was highlighted recently by The Independent a parliamentary debate offered some welcome signs that there could be greater understanding and flexibility on the part of the government.

We dare to hope for some positive second thoughts here, too, if only that the Afghan pilot and those like him should be given more time and more help to find accommodation, which is a precondition for becoming self-reliant and joining the mainstream. The alternative is that progress in some respects, such as reducing the backlog of asylum claims, becomes counterproductive, plunging more refugees into homelessness, even destitution.

Afghans are currently the largest national group of asylum-seekers. Many are here because of the help they gave to British forces against the Taliban and the threat to their lives as a result. These individuals have already proven their loyalty to the UK.

They should not have to resort to people traffickers and risk their lives further to reach safety here. Nor should they face destitution as a result of a successful claim for asylum. The air force pilot we have singled out stands for thousands of other Afghans who endangered their lives when they served the British, and deserve far better than they are currently receiving in return.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments