Soon after the 9/11 attacks on the United States, when it had become clear who was behind the atrocities, President George W Bush addressed Congress and declared: “On September 11, enemies of freedom committed an act of war against our country … Our war on terror begins with al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.”

The template for American policy for the next two decades was set; a nation at war, a “war on terror” and one that would not end until unconditional surrender had been secured. America was, though it is sometimes forgotten, supported in this struggle by its Nato allies, by friendly nations around the world and its intervention in Afghanistan was endorsed by the United Nations.

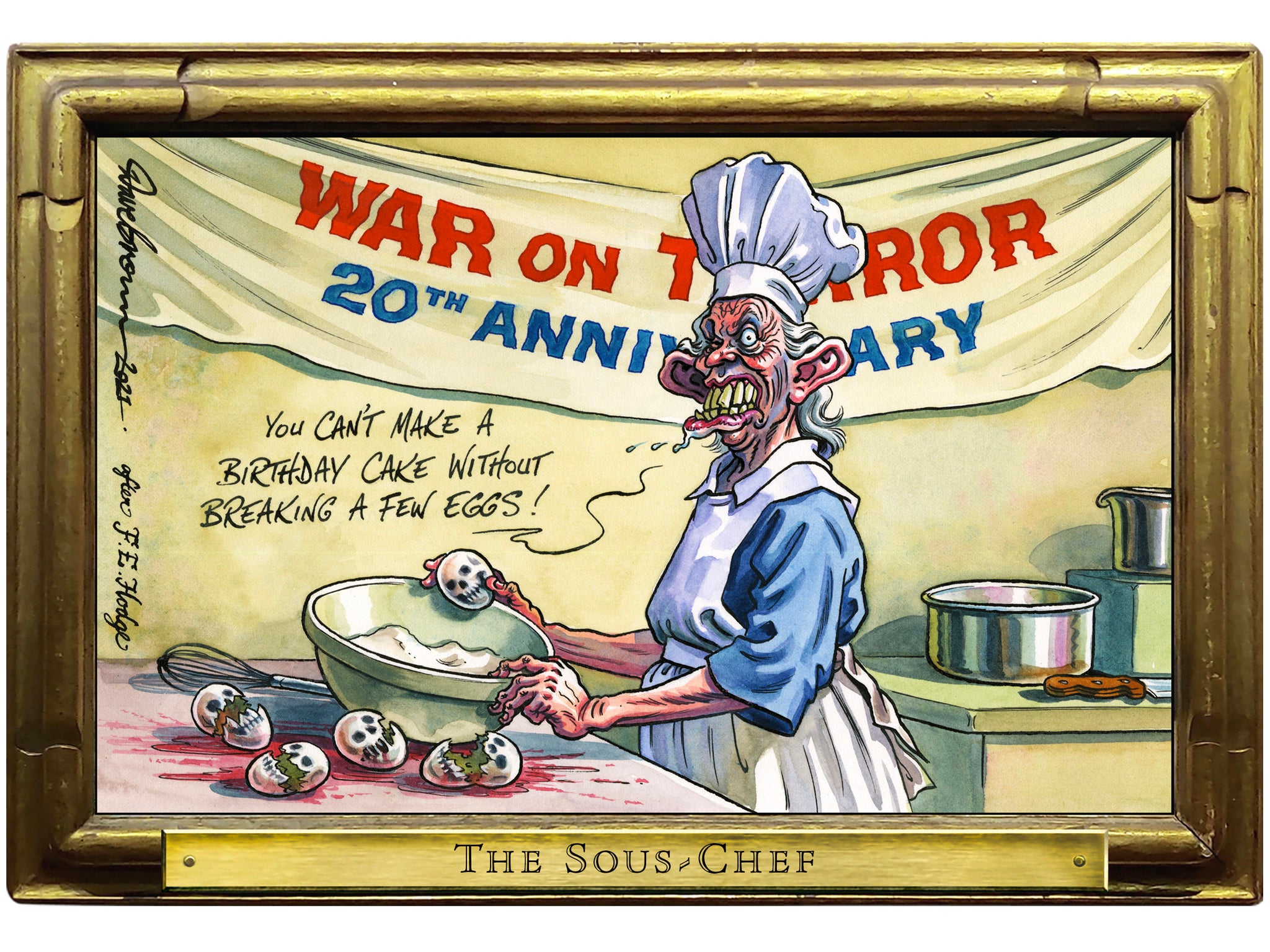

Even so, it was the first, foundational mistake the west made in responding to the challenge of militant Islamists. It should not have been a “war” at all, but a careful, slow rounding up of those responsible. Osama bin Laden’s aim was always to provoke America into massive, indiscriminate retaliation and to foment the much-discussed “clash of civilisations”. America, in shock and hurt, duly obliged, lashing out with huge bombing raids and the destruction of much of whatever primitive infrastructure and stability Afghanistan possessed.

As the asymmetric war in Afghanistan started to go wrong it was clear that America was following the failed strategy in Vietnam, relying on a client government to hold back a more nimble and ideologically driven movement. In the end, Bin Laden was assassinated through patient intelligence gathering and special forces in Pakistan, rather than being caught in a rain of bombs. It proved the point, though by then it was too late.

America also suffered terrible, fatal overreach when George Bush followed up the still unfinished war in Afghanistan with an invasion of Iraq. Afghanistan might have been pacified had America concentrated on making good its military progress. Instead, by 2003 Mr Bush decided to complete the unfinished business left by his father after the first Gulf War of 1991, and secure “regime change” and the removal of Saddam Hussein. The world now knows how futile that effort has been.

Without the war in Iraq, as another front in the “war on terror”, Isis would probably not have become the force it did by 2015. Which might have meant millions would not have fled their homes, and the refugee and migrant crisis across Europe might have been averted. Such are the unexpected, unintended consequences of 9/11 still reverberating around the world.

The war on terror, whatever that meant, did not begin on 9/11 and continues in some form. Al-Qaeda, Isis and their ilk can shrink and fade away, but they have the potential to return. At times they operate as large organisations and military powers with soldiers and officers and commanders; but they are also loose “franchises” – with propaganda being able to spread online and individuals or small groups being able to do great damage.

Twenty years on, with the Taliban back in power in Kabul, and with a huge arc of instability, conflict and war stretching across a number of regions, it is not hard to see the fruits of Bin Laden’s desire to spread chaos, suspicion and hatred on a vast scale.

The war on terror looks far less winnable now than it did on 9/11.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments