The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

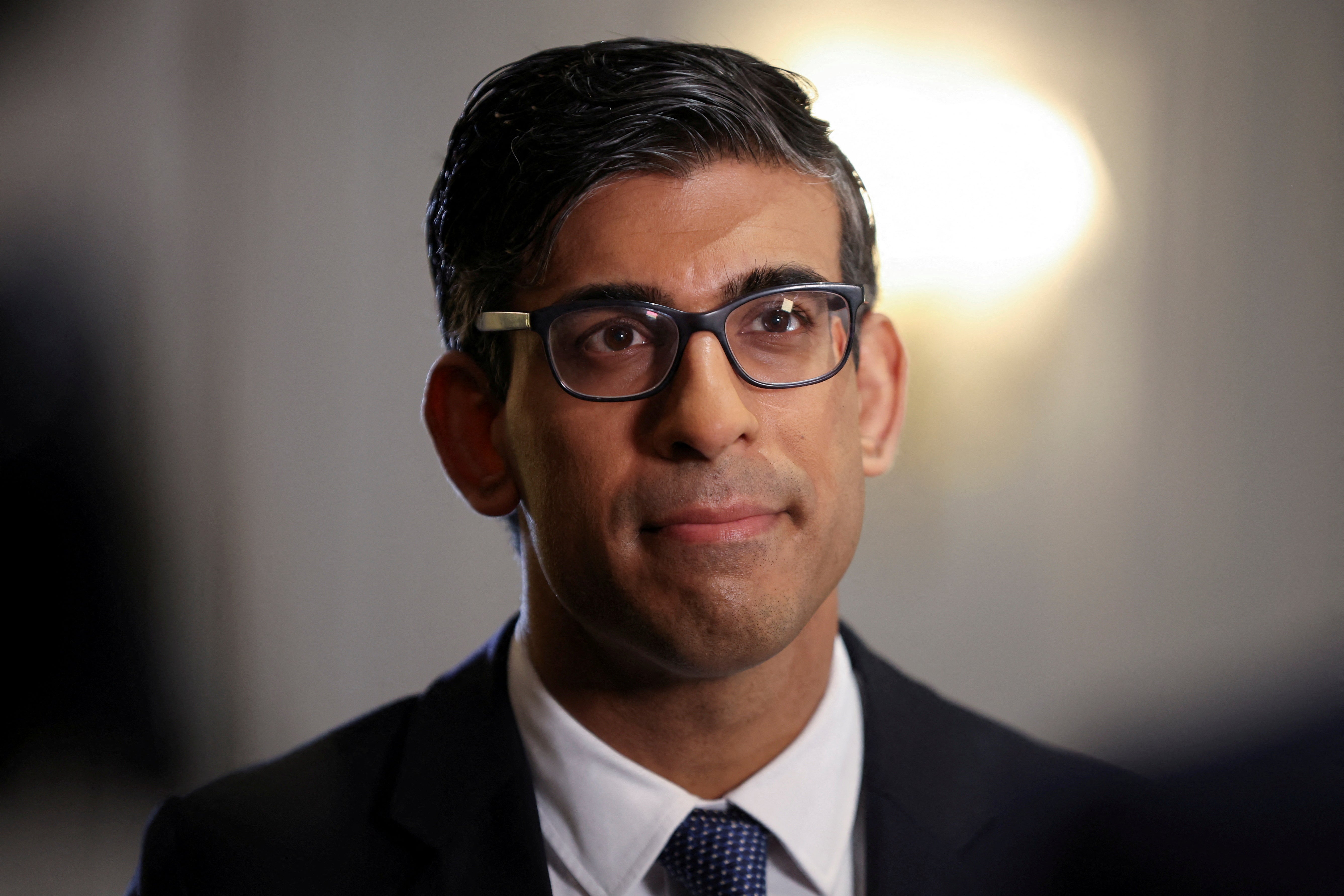

If the economy decides elections, Rishi Sunak looks doomed

A new academic study analyses the link between economic performance and election results, writes John Rentoul

The second slogan that James Carville wrote on the whiteboard in the Bill Clinton campaign war room in 1992 was: “The economy, stupid.” I am not allowed to mention it, because it became such a cliche, especially with an erroneous “it’s” in front of it, that I had to put it on the Banned List, but it remains an eternal truth of winning and losing elections.

George HW Bush lost to Clinton mainly because the US economy went into recession at the wrong time in the electoral cycle. Hence the significance of today’s headlines in Britain, suggesting that the economy will shrink by 0.3 per cent this year, with the IMF predicting that the UK will be the worst performer in the G7.

By coincidence, the Carville doctrine has been put to the test in a working paper published today by Professor Stephen Fisher of Oxford University, which looks at UK general elections since 1922 and the state of the economy. It concludes that “governments in the UK tend to win elections, but lose if there is an economic crisis”.

In the 13 elections that were not preceded by crises, the incumbent government was re-elected 10 times, Prof Fisher finds. In the other 14 elections, which followed crises, the government lost nine times.

The results do not suggest an iron law. They leave room for free will and the sheer unpredictability of politics, but Prof Fisher narrows the scope for that unpredictability further by adding another rule.

He observes that in three cases, after an economic crisis the government changed prime minister and went on to win: in 1922, after David Lloyd George was ousted in favour of Bonar Law; in 1959, after Anthony Eden gave way to Harold Macmillan; and in 1992, after Margaret Thatcher was defenestrated and replaced by John Major.

The recession of 1956 didn’t leave much of a mark on history: it was a shallow dip, a technical recession in the second and third quarters, easily eclipsed by the “never had it so good” boom that followed.

I don’t think it could really be called a “crisis” – unlike the political and diplomatic disaster of Suez, which is what really destroyed Eden’s standing. You could argue that the 1959 election should simply go into the first category of elections, those held after calm economic periods that the government usually wins.

Others might quibble with other of Prof Fisher’s classifications. James Callaghan took over from Harold Wilson and lost, for example, but I would argue that the worst of the economic crisis came after the change of prime minister.

You can see why Prof Fisher is tempted to make an exception to the exception to the rule. Because Rishi Sunak’s plan is to defy the fallout from the economic turmoil since 2019 by being a new face at the top. He hopes, like Major and Law, to escape the blame for the decline in living standards.

Prof Fisher says his model is “designed to help explain the past rather than forecast the future”, but admits that “it could be used to generate a crude forecast for the next election”. Crudely, he says, the Conservatives “should win the next election unless there is a recession under Sunak’s watch”.

Today’s news from the IMF suggests, then, that the Tories will lose – although the chances of a technical recession, which is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative growth, are well within the margin of error. In recent quarters that definition has just been avoided when figures are revised.

But if the IMF forecast leaves Prof Fisher’s model in the balance, there are other reasons for thinking that Sunak’s chances of winning are slim. Prof Fisher says that “this is an extraordinary electoral cycle”, because national income dropped by 11 per cent in 2020, “the largest since the Great Frost of 1709”.

He says that, with inflation still high, “real incomes falling, strikes, and public services in disarray, there is arguably a severe current economic crisis even without a technical recession”.

In other words, although the odds must be against Sunak, Prof Fisher’s analysis has not closed off all the space for creative politics and unexpected events. In recent months, there has been a lot of commentary comparing the coming election to previous contests, in 1992, 1997 and 2010. Prof Fisher tries a more systematic comparison with all general elections over the past 101 years.

His conclusion may be no more profound than Carville’s slogan, from a different political system across the Atlantic: that the economy is important, but that it always leaves scope for political leadership – on either side, government or opposition.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments