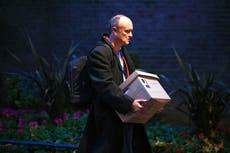

No, Dominic Cummings did not win the election for Boris Johnson

In fact, everything Cummings advised went horribly wrong and nearly doomed the whole enterprise

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

The instant obituaries of Dominic Cummings have one thing wrong about his legacy in British history, I think. He is undoubtedly a brilliant and unusual campaigner, and must take more credit than anyone other than Boris Johnson for winning the referendum to leave the EU.

But he didn’t win last year’s general election for Johnson, whatever Charles Moore, Margaret Thatcher’s official biographer, says. In today’s Daily Telegraph Moore says, “Mr Cummings understood that Boris Johnson was the only political leader unconventional enough” to overcome the House of Commons resistance to acting on the result of the referendum. Cummings “therefore devised a strategy for him” which prevailed, “winning the biggest Tory majority since 1987”.

In fact, everything Cummings advised went horribly wrong and nearly doomed the whole enterprise. It was Johnson’s skill in negotiating a new withdrawal agreement with Leo Varadkar, the Irish prime minister, that made the election possible. In those talks Johnson was advised by David Frost, his EU negotiator, not by Cummings.

That breakthrough started to dissolve Labour unity, which prompted the historic miscalculation by Jo Swinson, leader of the Liberal Democrats, in agreeing to an early election. I wonder if we will ever get to the bottom of exactly what happened in those few days last October – Chris Bryant, the Labour MP and historian of parliament, hints at low politics but says we will have to wait for the publication of his diaries for the full story.

What we know is that the Scottish National Party wanted an early election, confident of gaining seats, but didn’t want to be seen to be enabling Brexit. The SNP alone could have given Johnson the majority he needed to call an election, whereas the Lib Dems on their own could not have guaranteed it – on the raw numbers they would have been two votes short. But when Swinson decided to go for it, that gave the SNP the cover they needed and Johnson the votes he wanted. At that point Jeremy Corbyn, not wanting to look frightened of the voters, said he wanted an early election too. (In the end, both the SNP and the Lib Dems abstained, on the grounds that they wanted a different date.)

What won the election for Johnson was Swinson agreeing to let him hold it in the first place. Corbyn played a minor part in that turning point, and a rather more significant one in determining the outcome, but in a “Get Brexit Done” election against a weak Labour Party the result itself was never in much doubt.

There were other details to be sorted out along the way. Nigel Farage’s decision to stand down half the Brexit Party candidates helped the Tories, but the Brexit Party was already a spent force in the opinion polls.

The Tory campaign, which was competent and centrist, unlike Theresa May’s, was run by Isaac Levido, not Cummings. Levido had insisted on total control of the campaign – thus putting right one of the biggest flaws in May’s campaign – to which Johnson and, just as importantly, Cummings had agreed.

None of the pre-election antics inspired by Cummings had done any good. Proroguing parliament was a foolish idea that would have had no effect on Brexit even if it had been allowed to run its course. Parliament had already passed a law – the Benn act – to prevent the UK leaving the EU without a deal on 31 October. Cummings enjoyed the spectacle of Remainers winding themselves up into a froth about the possibility of Johnson breaking the law, but in the end the prime minister wrote the letter asking the EU for an extension and life went on.

The high drama of the government being defeated in the Supreme Court is supposed, in the eyes of admirers of Cummings’s cunning plans, to have pitched Johnson as the leader of the people against the Remainer establishment. But this is mysticism masquerading as political strategy. The appeal of “Get Brexit Done” was strong enough not to need dramatising in such a way – indeed the Cummingsesque antics might have put off some people who voted Remain but who thought that the referendum should be acted upon.

I think Cummings’s place in history is secure enough for his role in the referendum. “Take Back Control” alone was a deceptively simple slogan of genius. He brought something to Johnson’s No 10, too, mainly by being the one person who was prepared to make decisions, even if they weren’t always the right ones. But he didn’t win the election. That was Swinson, Corbyn, Johnson, Frost and Levido, in roughly that order. In that fight, Cummings was a spectator.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments