David Cameron was right to demand reform – and the whole bloc should be allowed to take advantage of the results

The EU would benefit from the reforms sought by the UK Government

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

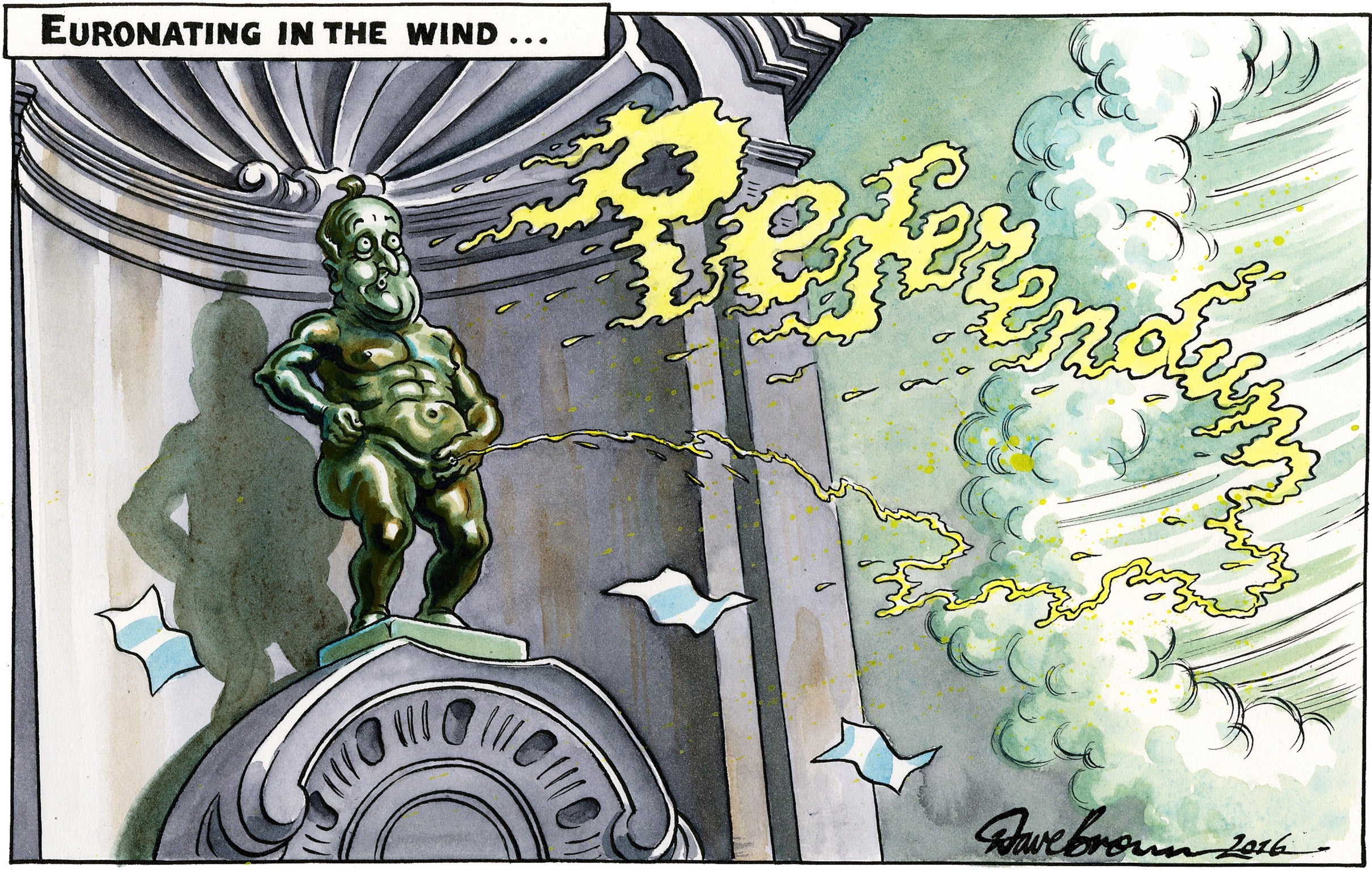

Your support makes all the difference.When the draft EU reforms negotiated by David Cameron were announced at the start of this month, plenty of domestic voices were heard arguing that he had achieved too little. Yet it is now becoming clear that for some EU member states the reforms go much too far. Others, meanwhile, are starting to wonder whether the exceptions the Prime Minister has sought for the UK might not be rather good for them as well. Mr Cameron’s seemingly mild reforms have opened a can of worms.

In particular, Spain is keen on the move to limit the sums which EU migrants can claim via child benefit payments for children still living in their country of origin. The overall amounts involved might be small – the current cost to the UK of paying such benefits is estimated at around £30m. Nonetheless, the existing policy is illogical and the proposed changes will strike a chord in various countries where net immigration from other parts of the European Union is relatively high. The so-called “brake” on other in-work benefits and social housing is also likely to find favour.

Lining up against Mr Cameron’s reforms, however, is the Visegrad Group – the bloc comprising the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary and Poland – which is averse to any measures which will make it more difficult for its residents to benefit fully from the EU’s freedom of movement principle. The French have anxieties about the Prime Minister’s attempt to carve out non-euro countries from eurozone regulations.

All of this wrangling over what are, in truth, fairly modest and reasonable proposals shows why EU reform is needed. Positive force though it is, the more it seeks to direct or harmonise the policies of its disparate and growing membership, the more room there is for disgruntlement. The EU was established to secure peace in Europe. That the bulk of the continent has experienced 70 years free from war is the most significant marker of the EU’s success – and, even now in a very different world, is arguably the primary reason why it cannot be allowed to fall apart. On other issues where pan-continental interests fundamentally coincide – crime prevention and climate policy for instance – the EU has proved effective. And as a trading entity, it has given its members greater collective bang for their divided buck.

But as the refugee crisis showed only too clearly, when individual EU members – or rival blocs – have sharply competing interests, all the Brussels bureaucrats in the world aren’t enough to iron out differences of opinion. And even when agreements can be reached on paper, their impact on the ground can be rendered meaningless – remember the hoped-for refugee quotas. This isn’t to say that the EU should avoid difficult issues. In any multinational political body there will be areas of disagreement – and it is better that there should be a forum in which to debate them sensibly. But the current discussions about possible reform should be a springboard to a general recalibration of the EU towards a more tightly focused agenda – one which is founded on high-level diplomacy, not low-level, inefficient bureaucracy.

In this respect, Mr Cameron’s personal involvement in the kind of shuttle diplomacy he has previously shunned during his prime ministership could – and perhaps should – be a sign of things to come. It is undoubtedly in Britain’s best interests to be inside the EU. But just as truthfully, the EU would benefit from the reforms sought by the UK Government – and it would profit too from a more fully engaged Britain should the forthcoming referendum produce a vote to remain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments