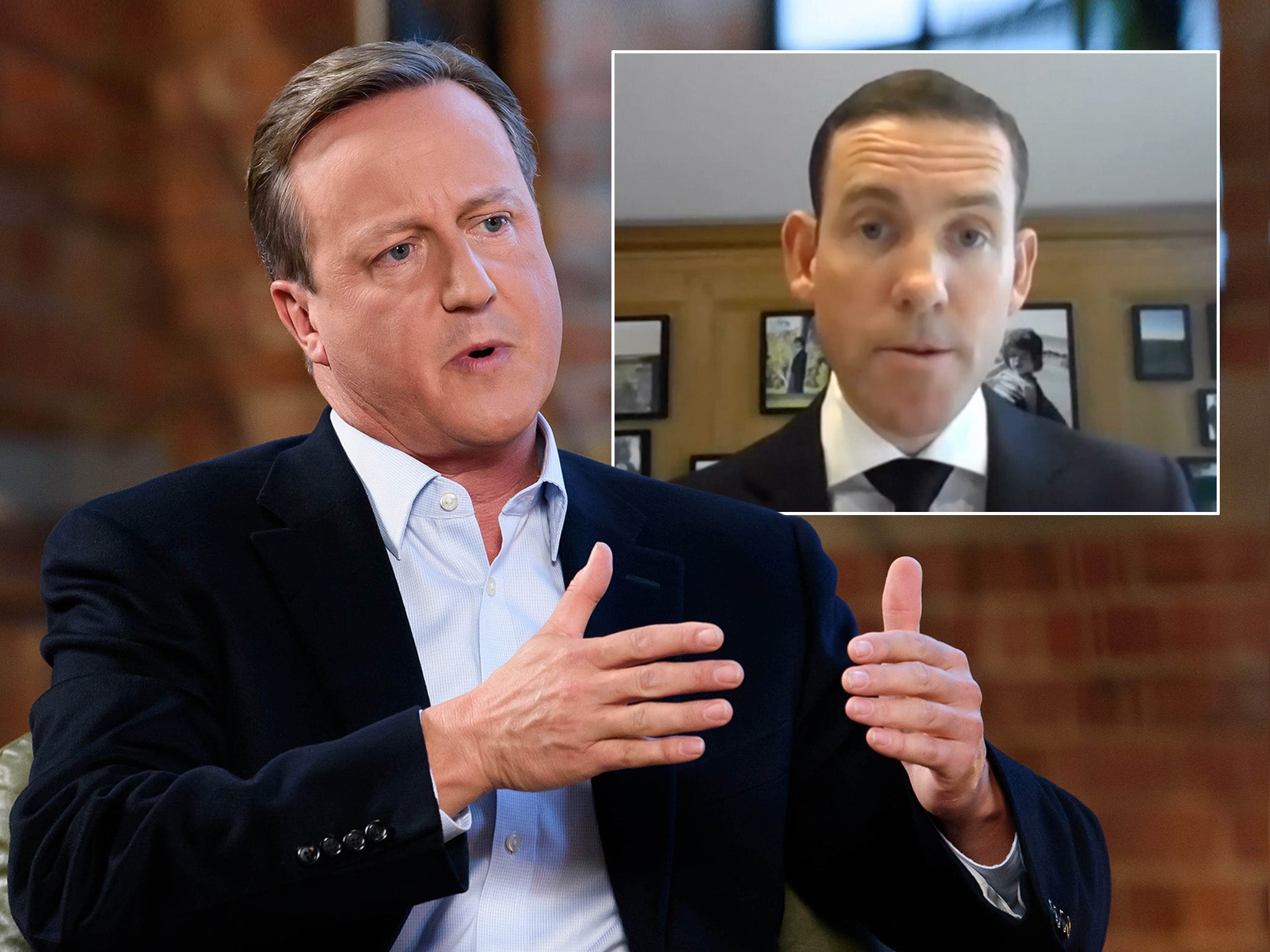

It’s hard to know which are more embarrassing, David Cameron’s desperate texts or the replies

If Alexander Greensill feels let down by the former prime minister, he does have a small country called the United Kingdom with which to share his pain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is hard to know which is more embarrassing for the former prime minister. Is it the 60 text messages themselves, sent essentially to every single powerful person in the country, desperately begging for help for Greensill Capital, which is now under investigation by the Financial Conduct Authority over “potentially criminal activity”.

Or is it the replies, in which absolutely everyone whose number he can get hold of – the full power and weight of the contacts book of an ex-prime minister (for which Lex Greensill paid him share options that would have been worth £50m if the pair of them had somehow been able to stop the company collapsing) – very politely answers with their own variation on a theme of “new phone, who dis”?

Did Michael Gove “have a moment for a word”, on the number on which Cameron was, in his own words, ‘“v free”? No, he did not. Perhaps that had something to do with the former prime minister calling his former best friend “a foam-flecked Faragist” in his 750-page autobiography, though, admittedly, fewer people read that than the average text message.

Would Tom Scholar, the top civil servant at the Treasury, help him out with a phone number? That’ll be a “no”, as well.

Still, none of this appeared to trouble the lacquered countenance of Alexander Greensill, who chooses to be known as Lex for the same reasons all Lexes choose to be known as Lex when Alex would be just fine, as he appeared before the Treasury Select Committee to explain, as is customary on these occasions, how nothing untoward had happened and nothing was his fault.

There had been considerable buildup for this rare look at a sort of self-made billionaire, even if the money was kind of imaginary and has now disappeared. It turns out that a self-made billionaire looks rather a lot like a Face Swap between Mark Zuckerberg and Pob the puppet.

What Greensill Capital did is shrouded in complexity, the shrouds having been endlessly wrapped around it by Lex Greensill himself, to the point, it seems, at which it ceased to matter whether there was anything at all beneath them, which it turned out there wasn’t.

Asked why his business ultimately failed, he explained how it was because, in the end, the insurance company insuring what he was doing decided that they didn’t want to any more. And this, apparently, was something for the Treasury Select Committee to go away and think about. That no one wanted to insure Lex Greensill’s business is, in his own view, a matter that the world of high finance may wish to stop and think about. When things don’t go as he wants them, it’s because there are structural problems in various interlocking industries that need to be addressed, and it’s definitely not because he’s not quite as clever as he thinks he is.

It’s purely anecdotal, but on the odd occasion that I’ve skimmed through the small print of various insurance policies over the years, what tends to invalidate them are things like Base jumping or concealing a terminal illness. It is dimly possible that in the labyrinthine world of insurance, not one broker could be found who thought what Lex Greensill’s firm was up to was sufficiently unlikely not to fall apart that it would be worth underwriting. Who knows? Insurance is not actually a human right, but it shouldn’t be hard to come by. You just need to convince someone that you’re telling them the truth. That’s all.

Of course, there is a less mysterious story here. As Warren Buffett once said, “When the tide goes out, that’s when you see who’s been swimming naked,” and with the Covid-19 tide going out last spring, Cameron’s texts are a vivid portrait of a man desperate not to be caught with his pants down but who now absolutely has been.

Maybe Greensill was unlucky. Maybe he really would now be sitting in one of his private jets somewhere, being paid by the government to pay the NHS’s bills for them, for reasons he managed to convinced them only he understood.

But then, maybe, when you hire a former prime minister, you might hope to get a bit more out of it. Still, if he feels he’s been badly let down by David Cameron, he does have a small country called the United Kingdom with which to share his pain.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments