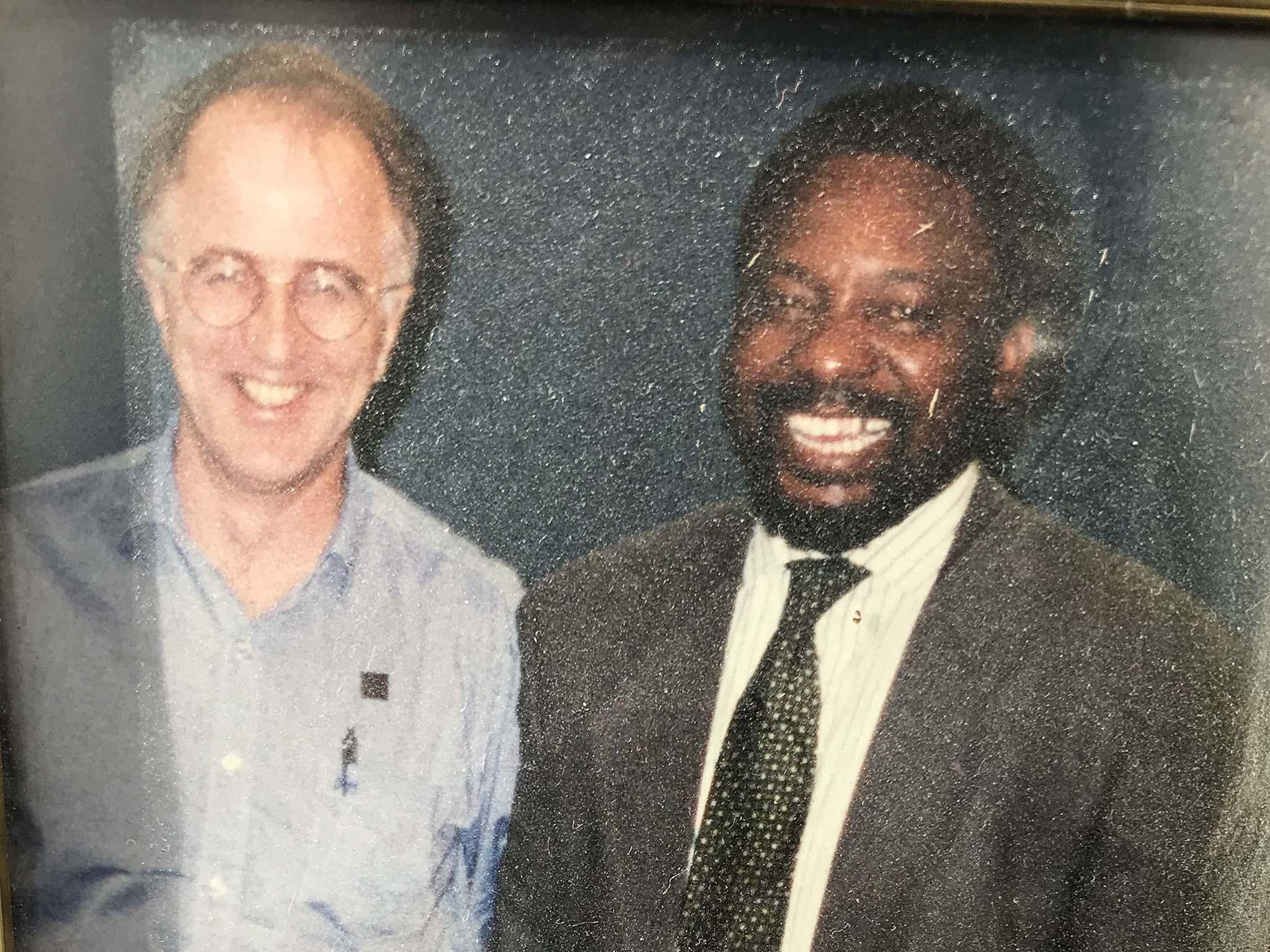

I used to work with South Africa's new President Cyril Ramaphosa in the 1980s – he is an impressive man

His most important immediate task is to recapture the state from those who have confiscated it for personal gain

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Cyril Ramaphosa has waited a long, long time to lead South Africa. He arrives as his nation’s leader at the same age as Churchill in 1940. When I first met him in the 1980s dreams of becoming president did not exist or at least not in any conversation I had with him.

But he was impressive, by far the most impressive South African I ever met in a decade of working with the black independent trade unions that grew into the force that effectively destroyed apartheid from within.

On Robben Island sat Nelson Mandela. In exile were ANC leaders like Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma. They were stupidly shunned by western leaders like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan so turned to the Soviet Union and the then impressive network of Kremlin connected and often Soviet financed communist parties and their linked trade unions around the world.

But the action on the ground was led by a group of young trade union leaders and left-wing lawyers from all racial groups in apartheid South Africa. They were inspired by the Polish Solidarity trade union movement and by Lula’s metalworkers in Brazil who used trade unions and working class organisations to challenge dictatorship.

In a book I wrote in 1984, I described Ramaphosa thus: “To organise the mineworkers, the independent trade unions sent one of their legal experts, Cyril Ramaphosa, to begin an organising drive. In two years (1982-84) the National Union of Mineworkers has become South Africa’s biggest black trade union, with 70,000 members. Ramaphosa’s calm, well-spoken manner belies a solid union organising ability. The NUM’s 180-page shop stewards manual, which he was largely responsible for drafting, is an impressive document.”

Ramaphosa is the first ANC president of South Africa who has spent his life within the country with his politics not formed by years of exile, or imprisonment in the case of Mandela.

He will not get a second chance to make a first impression as president. His most important immediate task is to recapture the state from those who have confiscated it for personal gain. The scandals over the Gupta brothers, Bell Pottinger, London-based accountancy, legal and consultancy firms, Vladimir Putin and a raft of corrupt politicians became so putrid they ended Zuma’s career.

There are a number of ministers implicated in the corrupt end years of Zuma’s rule that simply have to be fired. One of the biggest examples of corruption is the £79bn deal with the Kremlin to build a giant nuclear power station using uranium from a Gupta-owned mine.

South Africa is rich in coal and hydro and has no need for a nuclear plant that would increase foreign debt by a third and involves billions in loan repayments. Zuma defended the project on the grounds that the Soviet Union had helped the ANC before 1990 and therefore there was a debt to be repaid. Some believe that Zuma feared for his life if he crossed Putin.

There will be a desire to put on trial all those who enriched themselves from state capture under Zuma. Instead, Ramaphosa should be generous and let Zuma and his cronies retire quietly and under protection from any McMafia-style revenge killings.

Ramaphosa should send the Russian nuclear deal for examination by an international tribunal and meanwhile put it on hold. He ought to increase links with European Union investors. Countries like Germany and Sweden have long invested in South Africa. The EU’s leadership had better reach out quickly to South Africa under Ramaphosa with soft loans and preferential trade access, and help with education and social development. The new President should reinstate Pravin Gordhan, who was finance minister for nearly a decade until he was fired by Zuma last year. Gordhan has a solid record in resisting state capture by private billionaires, the Kremlin, or London based accountancy firms and managing the economy sensibly.

In fact, Ramaphosa could do worse than call to his side the South African-born ex-Labour minister Peter Hain, who has used his platform in the Lords to expose and denounce the behaviour of British firms who have been implicated in state capture.

Ramaphosa only narrowly won the presidency of the ANC and has enemies who dislike his comfortable bourgeois lifestyle. Nelson Mandela spotted his abilities early on and anointed him as his successor. But the entrenched factionalists of the ANC once returned from exile insisted their two men – Mbeki and Zuma – should become presidents.

Ramaphosa has bided his time. South Africa has never lost its independent press and judiciary and an understanding that it can only succeed on a multiracial basis. Recapturing the state so it serves the people is his first priority.

But the man whose smile lit up a room 30 years ago and whose soft-spoken but determined radicalism impressed anyone who met him at a young age is likely to emerge as a major world leader when he steps onto the international stage.

Denis MacShane is a former Labour MP who was a parliamentary private secretary and minister at the FCO 1997-2005. The book he co-authored with Martin Plaut and David Ward, ‘Power! Black workers, their unions and the struggle for freedom in South Africa’, was published in 1984

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments