Cynthia Lennon's death reminds us that artistic genius is no guarantee of decency

All the arts turn out to harbour some of the greatest spouse abusers and child neglecters

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

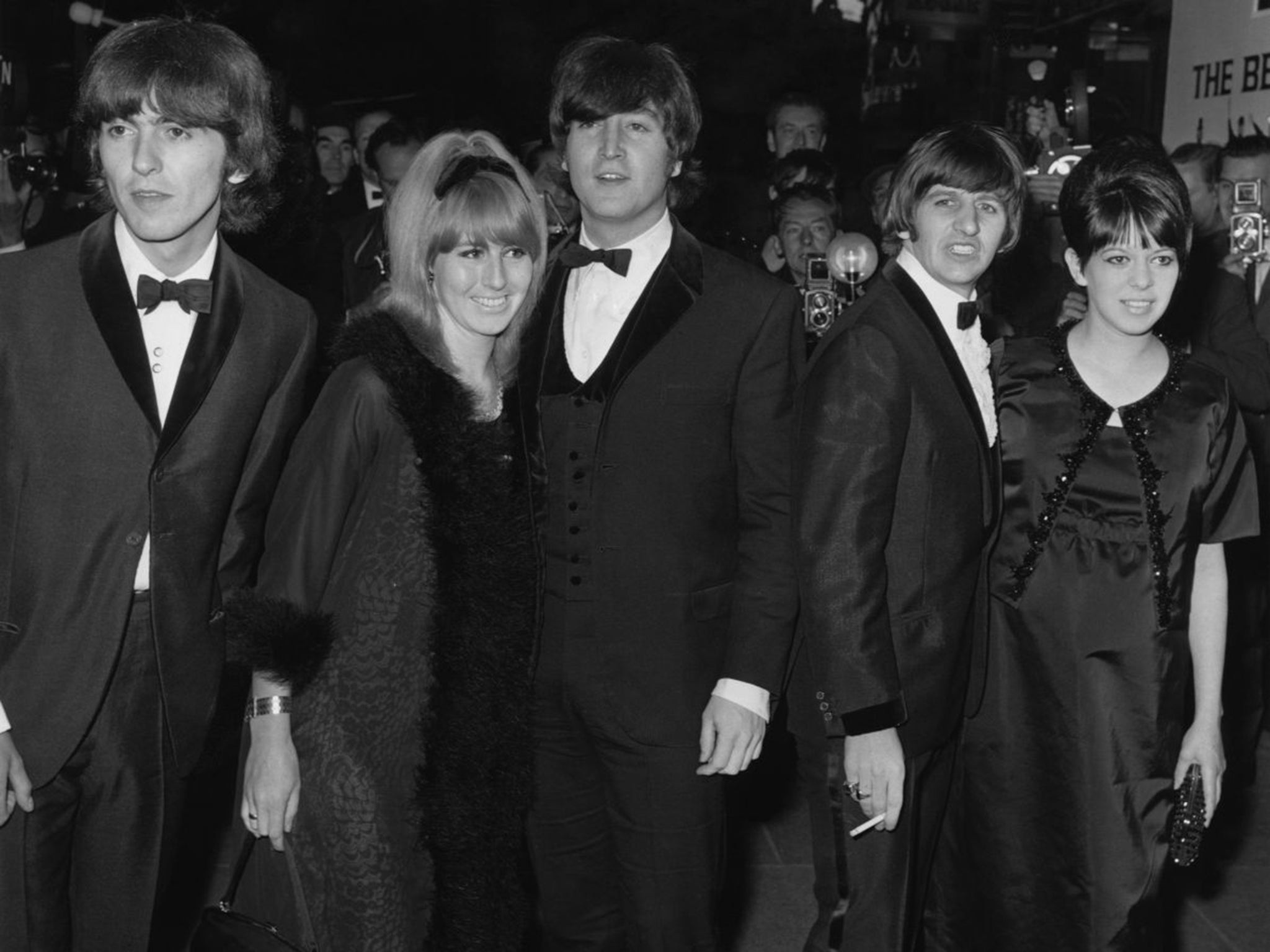

Your support makes all the difference.Even as a teenager, chancing upon the very few pieces of Beatles footage in which she makes a fleeting appearance, I always felt profoundly sorry for Cynthia Lennon who, for all her comparative longevity, had some claims to be regarded as one of the great rock casualties. Whatever the occasion – the receiving line backstage at the Royal Variety Performance, the Heathrow tarmac prior to an American tour – surviving photographs always make her seem exactly the same: a rather wistful-looking and exceptionally pretty girl who clearly worshipped her far-from-adoring swain and wanted nothing more than a conventional life by his side, someone who patently did her best with what the French call a mauvais sujet and found that it didn’t suffice. Why did Lennon write “Help” in 1965? Well, according to Ian MacDonald’s Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties, because “his marriage damaged by an orgiastic round of whores and groupies… he felt unsustained by his faithful and attentive wife”.

If it took the collective weight of the obituaries printed in the wake of her death last week to demonstrate what a truly awful time Cynthia had of it in the Sixties, then quite as awful, in some ways, was the symbolism that seemed to attach itself to this catalogue of humiliations and disappointments. Take, for example, the fateful morning when she returned to the mansion outside Weybridge to find John and Yoko clad in bath-robes and the sheets of the guest bedroom undisturbed, or the plane ride home from Rishikesh when Lennon decided to make a clean breast of his serial infidelities, or the dreadful moment in 1967 when, with the rest of the Fab Four and their entourage safely embarked to Bangor to meet the Maharishi, she found herself left stranded on the station platform. Worse even than the symbolism, possibly, was the underlying threat of violence. Recalling Lennon’s possessiveness and his uncontrollable rages, she once remarked that she “was really quite terrified of him for 75 per cent of the time”.

The curious, or perhaps not so curious, aspect of Lennon’s relationship with Cynthia, his first wife and the mother of his son Julian (for whom Paul McCartney, noting paternal indifference, is supposed to have written the morale-boosting “Hey Jude”) is how often attitudes of this type manifest themselves across the creative arts. Literature, music, film – all of them turn out to harbour some of the greatest spouse-abusers and child-neglecters who ever went off to commit adultery while the wife of their bosom was bending over the stove. Dickens, famously, not only abandoned his other half for a younger but wrote belittling letters to friends claiming that she had never loved their children and vice versa. Saul Bellow’s emotional life, we learn from the first volume of Zachary Leader’s authorised biography, published next month, was a riot of departures and betrayals, in which by far the most revealing comment is dropped by a woman named Eleanor Fox to whom he proposed in the late 1930s.

“You were mean, and volatile,” Ms Fox informed the Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning author many years and several marriages later. She had, she assures him, “recognised your genius, great emotional need and capacity to love” while feeling “unable to cope”. Had she married him at an early age, she concluded: “I would have been one of your five wives.” Literary history ought to spare a thought for the five Mrs Bellows, and the existences they led while old Saul was off writing his brilliant books and being a genius, just as pop history ought to spare a thought for the offspring of all those Sixties flower children, many of whom would have quite liked to live regular lives and not have Led Zeppelin coming to lunch on Sundays.

There is, of course, a context for this kind of behaviour, and it can be found in creative culture’s habit, at least since the Romantic era, of privileging the status of the artist and conferring on these titanic figures a licence not generally allowed to those smaller fry in their wake. Naturally, very few artists – and very few artists’ biographers – ever explicitly acknowledge this modern variant on benefit of clergy: after all, it takes quite a bit of courage to openly declare that because you are an artist the behavioural standards by which most people live their lives mysteriously don’t apply. At the same time the assumption that genius, or even an approximation of genius, explains, if it doesn’t quite excuse, one or two fundamental human flaws, weaves its way through the artistic sensibility like knotweed through a lawn.

Inevitably, there are distinctions to be drawn. One of them is between the artist and the art. If, as Orwell once put it, the second-best bed left by Shakespeare to his wife in his will doesn’t invalidate Hamlet, then neither does the racist, homophobic and misogynist banter of Philip Larkin’s letters to Kingsley Amis detract from the merits of The Whitsun Weddings. Every so often there wanders on to the bookshelves a book by a biographer much less astute than Zachary Leader which invites us, again without openly stating the fact, to think less of the films, the music or the poems of its subject because of the ghastliness of his, or her, private life. A useless endeavour, for one can think of dozens of famous artists who combined an unredeemed personal awfulness with the ability to write, or draw, or act like an angel, to the point where the latter quality is practically underpinned by the former failing.

Could Lennon have written, say, “I am the Walrus” if he were the rational, home-loving and conciliatory type whose existence is vital to the conventional society he so much deplored? Shouldn’t Cynthia simply have been grateful that she was a moth hovering around the flame of this singular talent? Questions of this kind invariably have a starkness that altogether ignores the day-to-day realities of life with another person, the fate that lies in store or indeed the value of the talent on whose altar you are about to prostrate yourself. There is, for example, a wonderful moment in Nigel Williams’s novel My Life Closed Twice (1977) in which the put-upon wife of an aspiring but as yet unpublished writer pointedly remarks: “Sorry Martin. Amanuensis to a Great Man’s a bit of a sticky one, but Amanuensis to a Mediocrity – sorry no deal.”

Lennon, alternatively, was one of the greatest geniuses of English pop, so none of these strictures apply. But how thoroughly one approves of all those writers, composers and painters who managed to stay at the top of their game without fathering 17 illegitimate children, bankrupting their dependents and brutalising their wives. To learn of the great Victorian savant Samuel Butler that the three things he disliked most were late nights, queer company and surprises is to infer that The Way of All Flesh and Erewhon ought to be worth reading. However much the creative mad-lads and the uber-bohemians might want to deny it, it is possible to be one of the most left-field and avant-garde artists on the planet and still contrive to lead a perfectly ordinary life. None of which, alas, was much consolation to Cynthia Lennon as she stood despairingly on the platform at Euston while the train-load of beautiful people sped off to Bangor without her.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments