The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

I teach critical race theory. This is what Republicans trying to ban it don’t understand

Most students come to me knowing barely anything about race. After a while, they’re hooked. And the truth is that there’s no legitimate place for white guilt in these discussions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

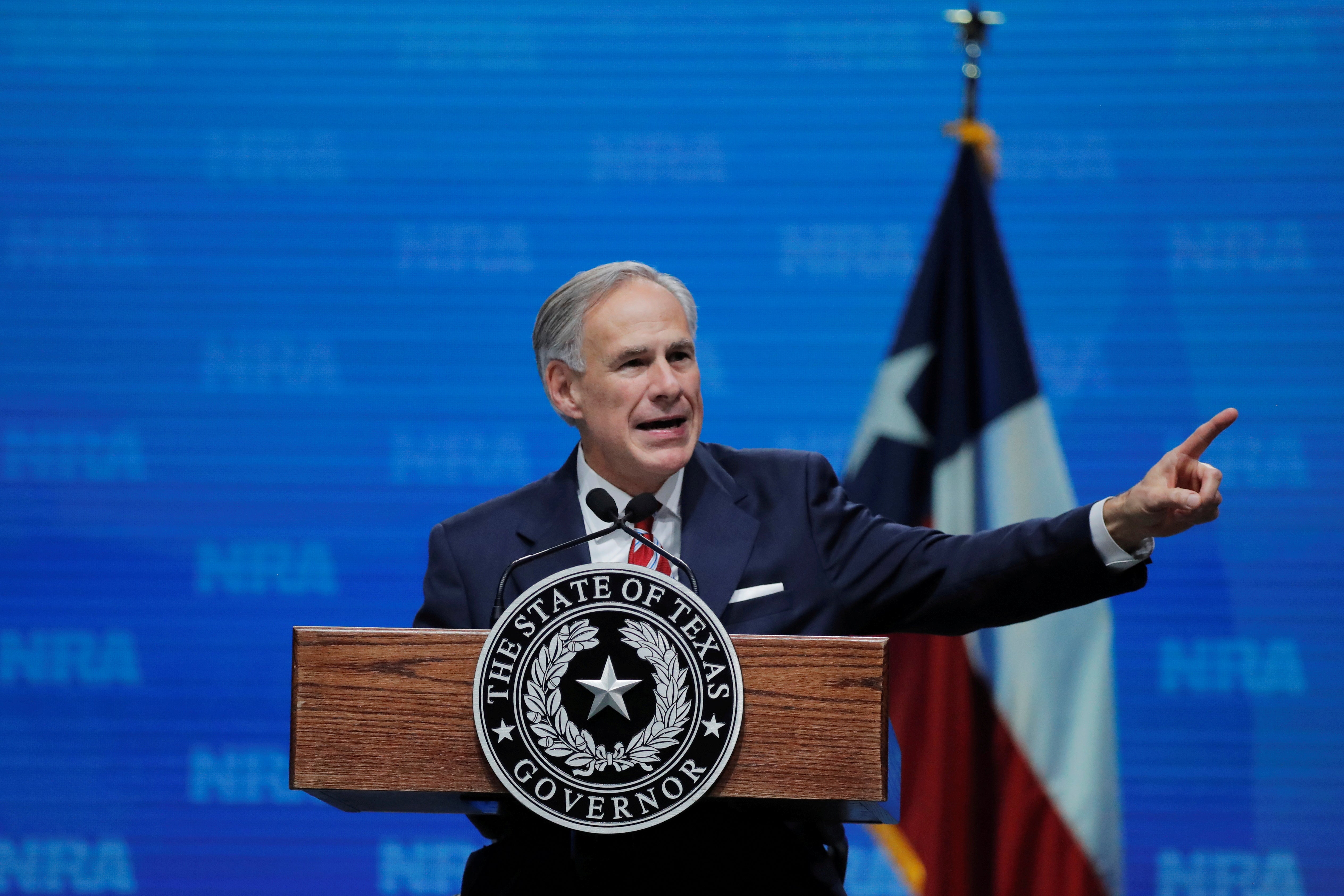

Your support makes all the difference.Republicans across the country are taking a stand against critical race theory. Texas Governor Abbott signed a law banning public schools from teaching the theory earlier today, not long after Florida did the same. An Alabama politician also hoping to ban CRT ended up getting tied in knots when asked to describe it.

The truth is that CRT is not some scary indoctrination topic about to be taught to your fourth-grader. Most K-12 schools have done little if anything to prepare students for thoughtful discussions about race and racism, and this was long before our politicians have ever even heard of the “evil” acronym. I know, because I teach it.

Specifically, I’ve taught CRT and whiteness studies to maxed-out classrooms comprising mostly rural and suburban white college students. In my courses, we examine race and racism in pop culture (e.g. music, film, books, and other texts) and institutions (e.g. schools and prisons) with semester-long attention to how our own experiences affect our assumptions about race.

The students enrolled in my CRT course span every major my regional university has to offer. Most of them are education majors, but I’ve also met business, psychology, journalism, nursing, music and environmental studies majors. A lot of professors would find it challenging to have to tailor a course to such a wide range of student interests. For me, this is exciting, but also depressingly easy. Unfortunately, there’s no shortage of stories about racism and white supremacy in America.

Early in the semester, I encourage students to conduct research on how race and racism have shaped their chosen fields, and the results are always telling: My nursing and pre-med majors haven’t a clue about medical racism, my business majors are often glommed to myths about affirmative action yet largely unaware that white women have benefited most from its policies, and my well-meaning education majors often arrive unaware of the racist underpinnings of standardized testing and preaching ideologies of color blindness. When my lone environmental studies student was at a loss for understanding how race and whiteness could possibly impact his future industry, I printed him a folder full of coverage of the Flint Water Crisis, a devastating environmental issue in which “race and class were factors in the authorities’ slow and allegedly dishonest response,” according to former Flint mayor Karen Weaver. My student read these pieces with an intellectual curiosity that reminded me of why I do what I do. He was embarrassed to have not, before that moment, thought of his field as anything but racially neutral and apolitical.

My environmental studies major stands out in my memory as symbolic of the ways that my students were united by a singular experience, despite their varied interests. The vast majority of them began college — and thus, my course — having come from predominantly white schools. Most of them shared stories about teachers who had no idea how to facilitate meaningful discussions about race and racism. One student talked about how she was publicly scolded for saying the word “white”, an embarrassing experience that discouraged her from ever wanting to discuss race ever again (I couldn’t blame her — I’d swear off these discussions, too, had my early schooling been marked in this way).

Most students begin my course ambivalent and fearful. By the end of it, they are examining everything from their predominantly white university’s racial enrollment statistics to pop culture’s representations of beauty and the lack of brown foundation in Target’s makeup aisles. One student treated the class — and myself — to an introduction to the University of Virginia’s Racial Dot Map, a tool that allowed her to visually assess the racial demographics of a given location, including the racial and ethnic disparities of state prisons. Our work together is fulfilling and enlightening and I learn right alongside them.

I will never blame individual students for how their education failed them in critical ways. I was thirty years old before I began to engage meaningful discussions about race and racism. And there is no legitimate place for white guilt in these discussions — only critical engagement followed by swift action and reparations. My ire will only and forever be on the politicians and their supporters who stop at nothing to perpetuate these failures. What supporters of banning CRT don’t seem to understand, in hiding behind the guise of neutrality and racial unity, is that outlawing examinations of race and whiteness is a choice in itself. It accomplishes nothing more than bolstering white supremacist thought and ideology. Or perhaps this is precisely the point.

The truth is that students are hungry for the knowledge that they get from critical race theory. And if the ones I know are any indication, there will always be people who find their way to CRT — our politicians are powerless to stop them.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments