We must listen to, not dismiss, anti-vaxxers

The government should bear some responsibility for the lack of confidence in a vaccine. Over-promising during the pandemic has eroded public trust; now communication with those who are sceptical is key

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

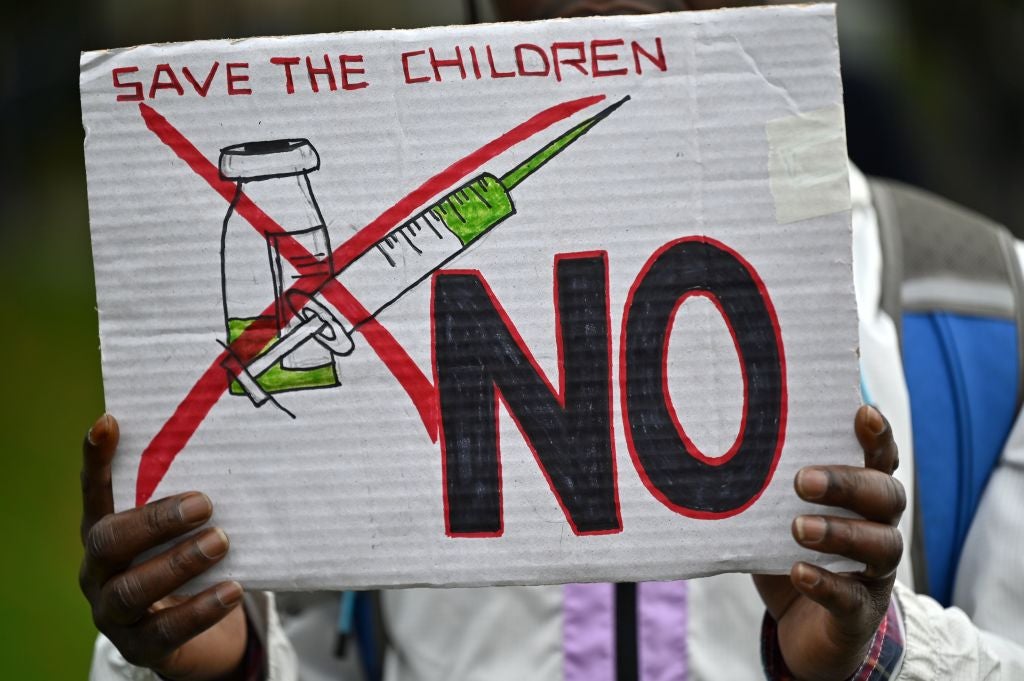

Your support makes all the difference.While some misinformation about the new Covid-19 vaccines is dangerous, the response of some to anti-vaxxers is equally dangerous. Calling people stupid or conspiracy theorists will do little to persuade them to change their view and risks placing individuals with a diverse range of views into one amorphous group.

The fallacy is to believe that any of us employ logic when making decisions. This breeds frustration as those trying to persuade can’t understand why given the “facts” those who think differently won’t see “sense”. A little personal reflection reveals some illogical decisions we all make. Some commercial enterprises profit from this, think gym membership, when we sign up we are full of good intentions but can barely remember where the gym is six months later.

We must engage rather than ignore those with concerns about vaccines. If the vaccination programme is to be successful, then approximately three quarters of the population will need to be vaccinated. If recent polling is accurate then we will need one in four who report being reluctant about vaccination to be converted.

The saying “that no-one wins an argument” applies to looking at some of the exchanges between the pro and anti-vaccine camps on social media. Accepting that the concerns are as varied as those holding them is a good place to start considering how hearts and minds can be won. These can be broken down into three broad categories, misinformation, conspiracy and concerns about safety.

It is unlikely that those holding fixed views of conspiracy theories, including the idea that Bill Gates plans to include a microchip in a vaccine, will be persuadable. But others are likely to be more malleable as long as we genuinely listen.

Those anxious about the safety and efficacy of the vaccine are not uneducated or drawn exclusively from one particular political or social group. Take a recent UK poll of doctors that found four in 10 would be reluctant to be vaccinated, reasons varied but more than half cited safety concerns. Given that health care workers like doctors are among those to be first in line to be vaccinated then we need them on board.

In some ways, we shouldn’t be surprised that such a high proportion of healthcare workers are vaccine sceptics. After all, they don’t routinely see people who are well, they are exposed to those who react badly to vaccines, sometimes fatally as a result of anaphylactic shock.

This bias exposure naturally breeds a skewed perspective which in any other walk of life would be viewed as a healthy tendency to question conventional facts.

This hasn’t been helped by vaccine producers limiting access to trial data, providing this could reassure some doctors and health workers. No vaccine is 100 per cent effective or safe, but a focus on problems rather than potential could be fuelling some of the hesitancy.

Irrespective of background, most individuals will be more open to an alternative view if they are discussing this issue out of public gaze and one to one rather than in a group. Changing your position on an issue like this isn’t just about logic but feelings and thoughts, shame is a powerful barrier to accepting an alternative view. Minimising this negative feeling is critical.

Employing that old cliché of “it’s not what you say, but the way you say it” offers some help. Rather than getting into a virtual shouting match where facts are exchanged, we know that people respond more favourably to storytelling.

Professor Jonathan Van Tam, the deputy chief medical officer, has been the master of the metaphor when making the case for the vaccine. He uses another clever linguistic technique when he talks about how each person vaccinated contributes to community immunity. This is more persuasive and acceptable than suggesting individuals contribute to herd immunity, the inference of behaving like sheep isn’t appealing.

The government is thinking of employing influencers in an effort to persuade people to get vaccinated, these endorsements will probably persuade some, but we need micro-influencers too. Those people who we are in contact with through work or leisure that we view as credible and trustworthy.

It is good to see the government consider more imaginative ways of communicating facts about vaccines, having a variety of approaches particularly if intelligence is used to match them to specific demographic groups will improve uptake.

Government ministers must bear some of the responsibility for the lack of trust and credibility in relation to Covid-19. Both Boris Johnson and Matt Hancock have consistently over-promised and under-delivered during the pandemic. Compounding this by denying or trying to cover up mistakes, doing little to convince those who now need to be persuaded that vaccines are safe and effective.

The achievement of biological science gives us the potential to inhibit the virus, but this will be thwarted by politicians who have been unwilling to admit to their fast and loose relationship with the facts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments